Теория графов

В переводе с греческого граф — «пишу», «описываю». В современном мире граф описывает отношения. И наоборот: любое отношение можно описать в виде графа.

Теория графов — обширный раздел дискретной математики, в котором системно изучают свойства графов.

Теория графов широко применяется в решении экономических и управленческих задач, в программировании, химии, конструировании и изучении электрических цепей, коммуникации, психологии, социологии, лингвистике и в других областях.

Для чего строят графы: чтобы отобразить отношения на множествах. По сути, графы помогают визуально представить всяческие сложные взаимодействия: аэропорты и рейсы между ними, разные отделы в компании, молекулы в веществе.

Давайте на примере.

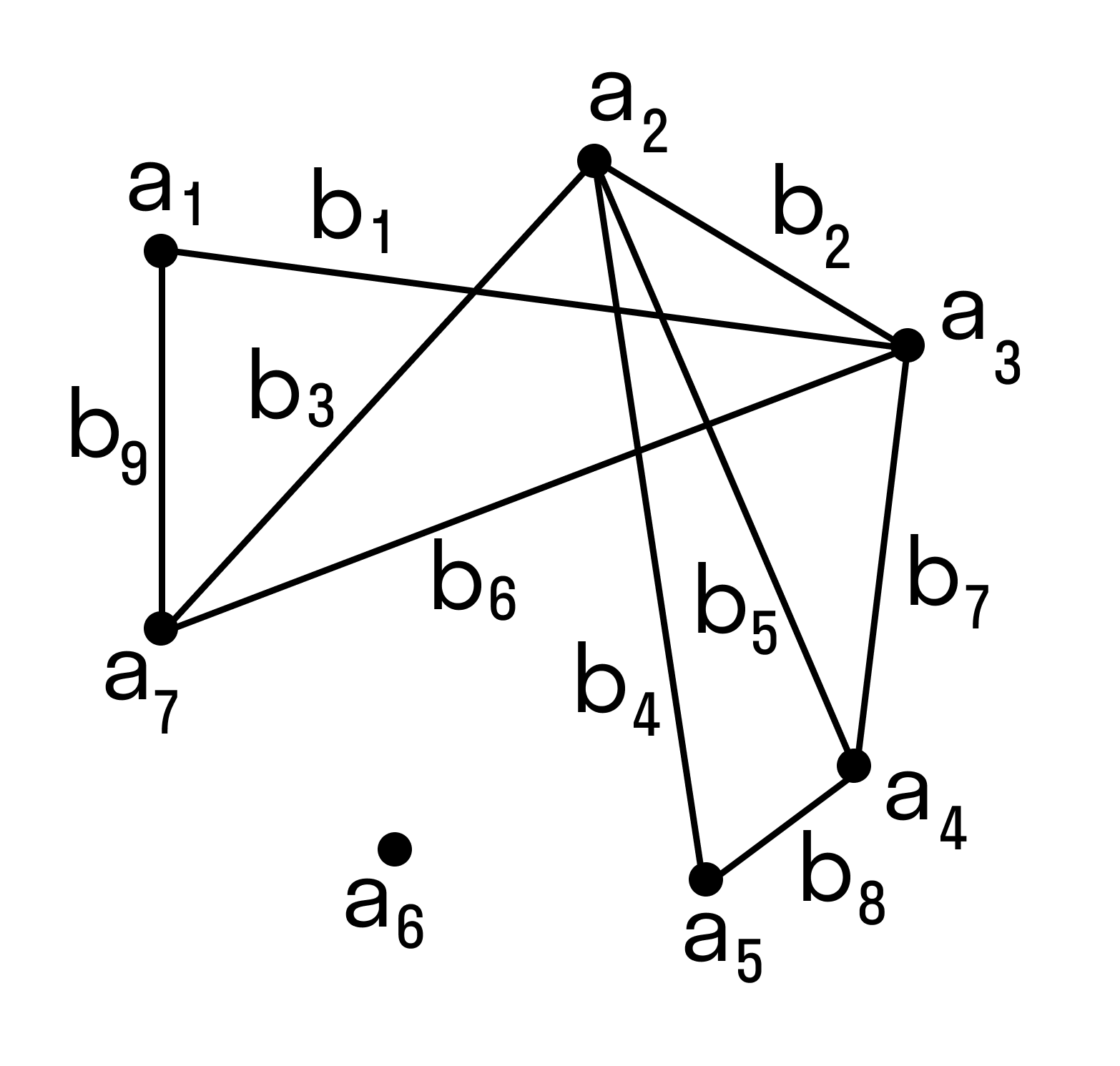

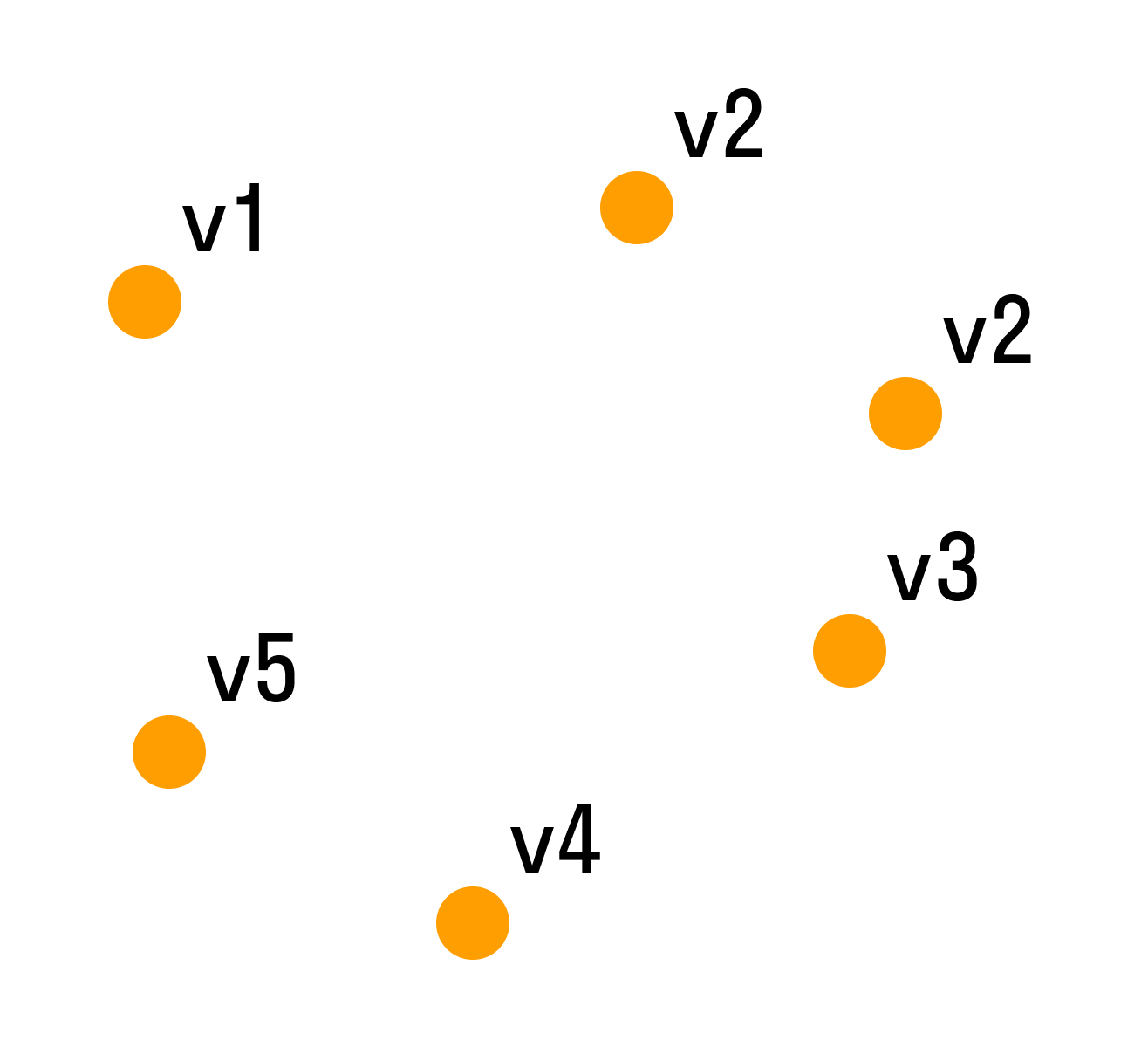

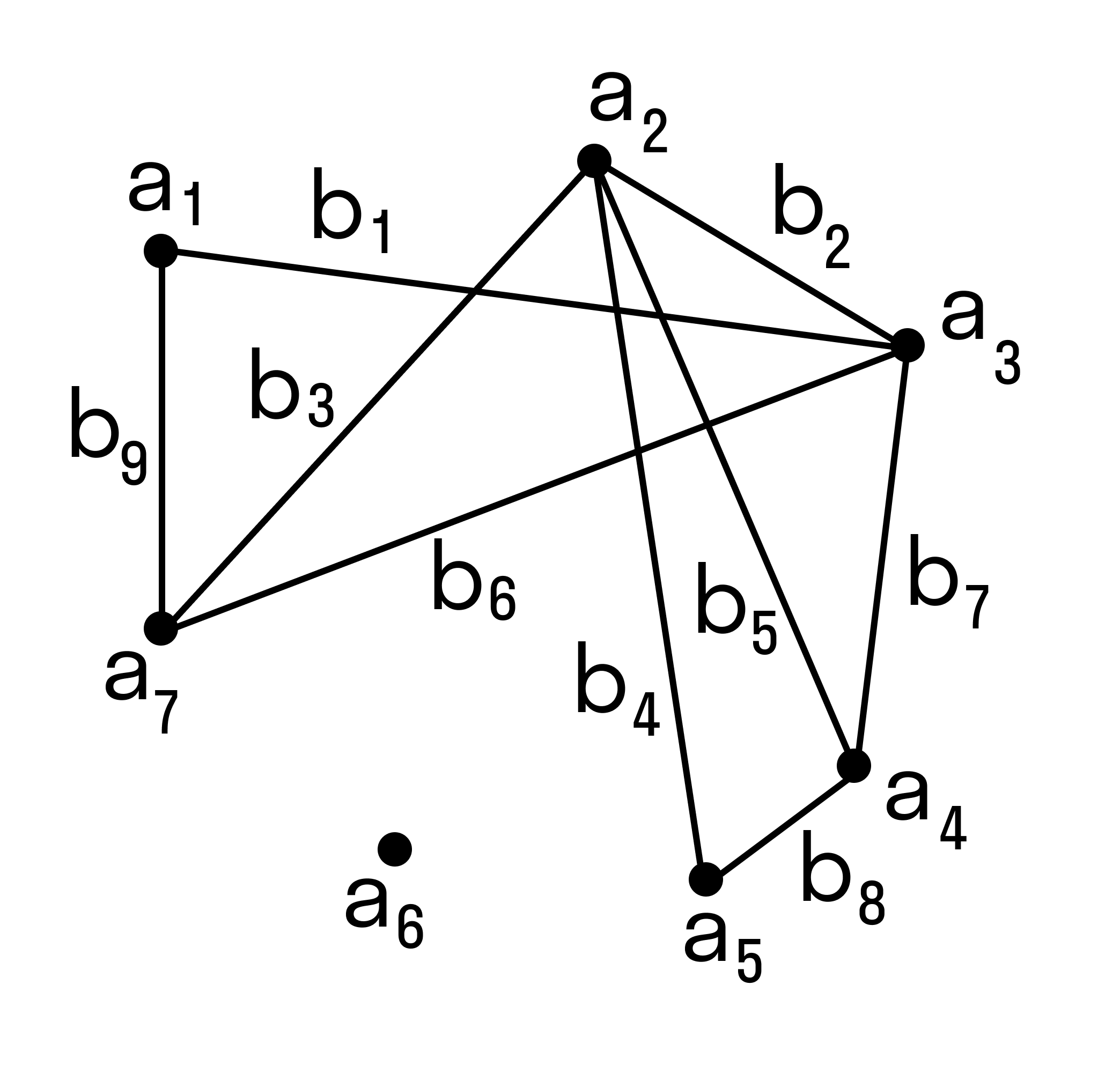

Пусть множество A = {a1, a2, … an} — это множество людей, и каждый элемент отображен в виде точки. Множество B = {b1, b2, … bm} — множество связок (прямых, дуг или отрезков).

На множестве A зададим отношение знакомства между людьми из этого множества. Строим граф из точек и связок. Связки будут связывать пары людей, знакомых между собой.

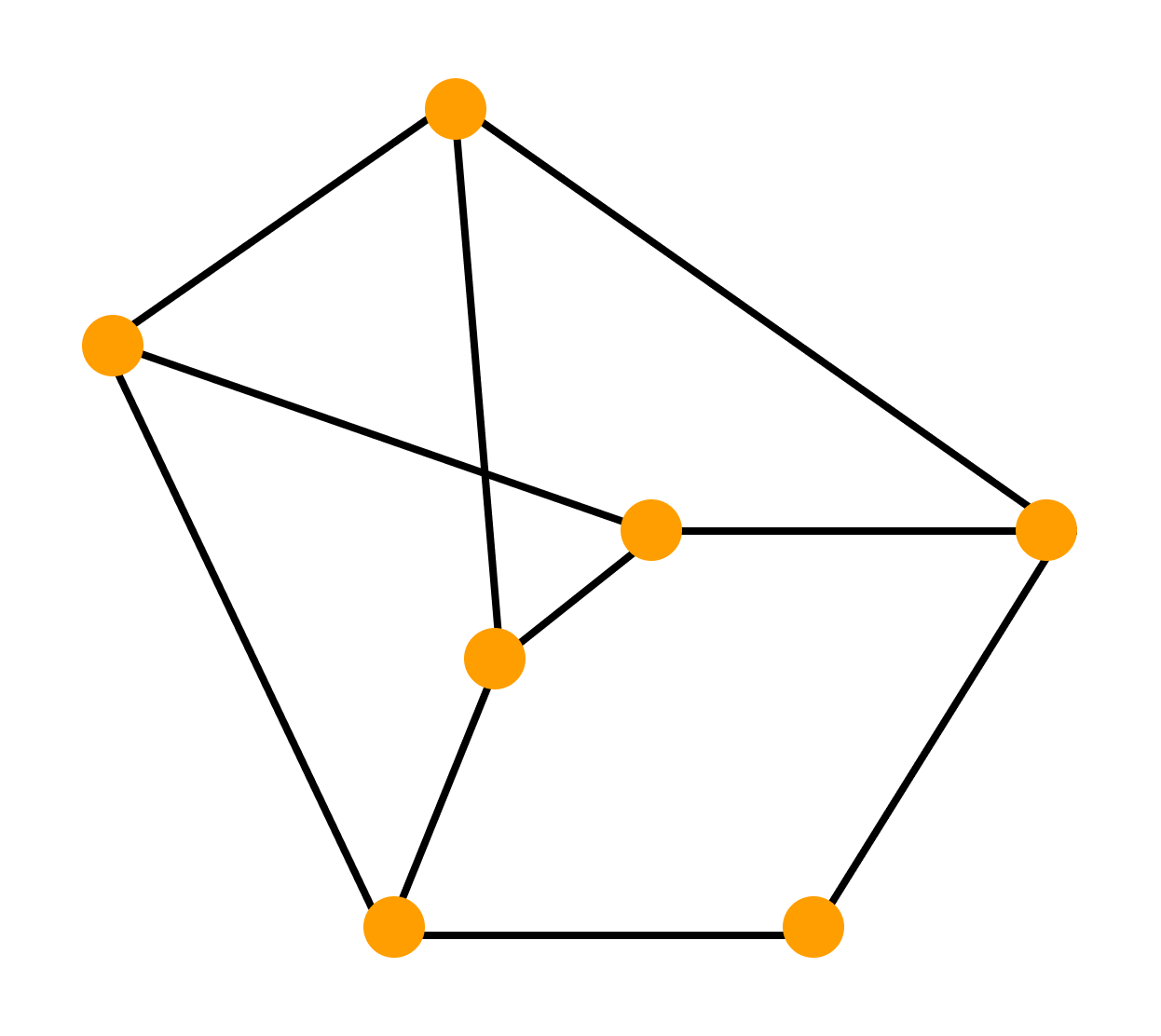

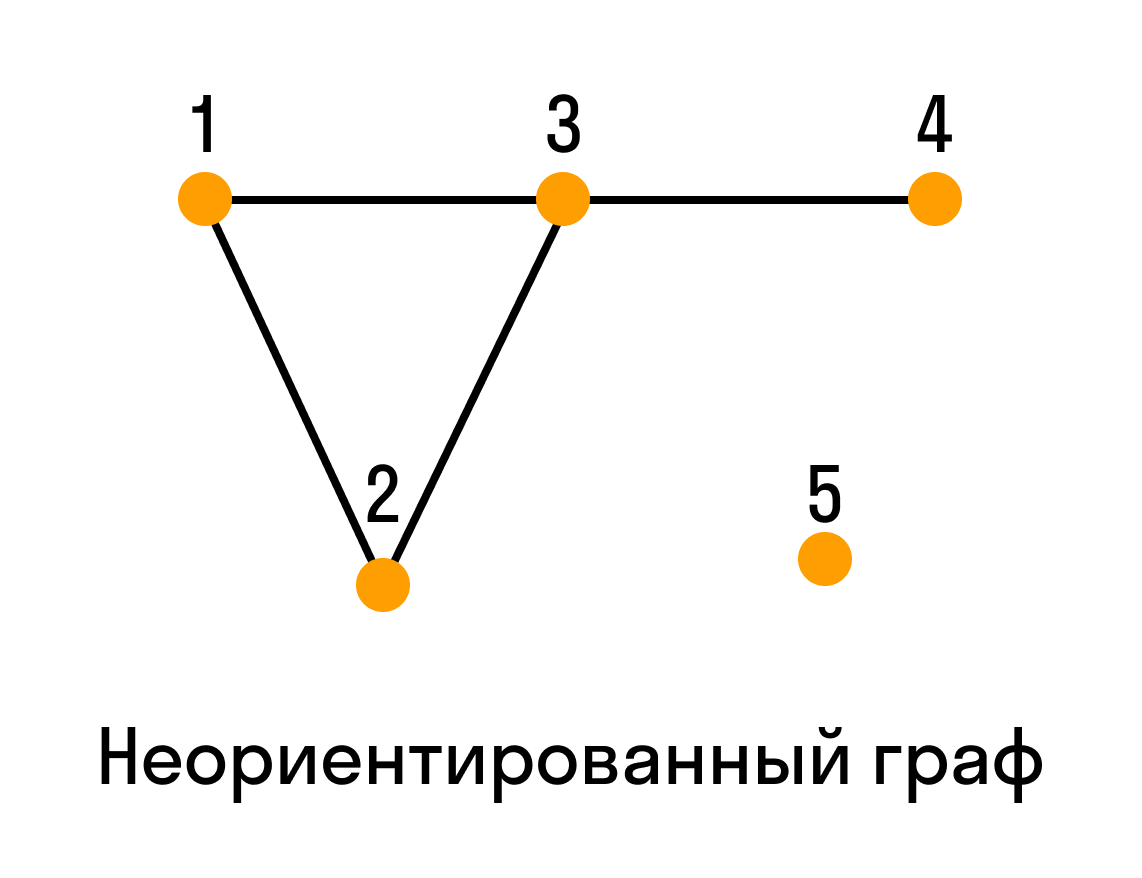

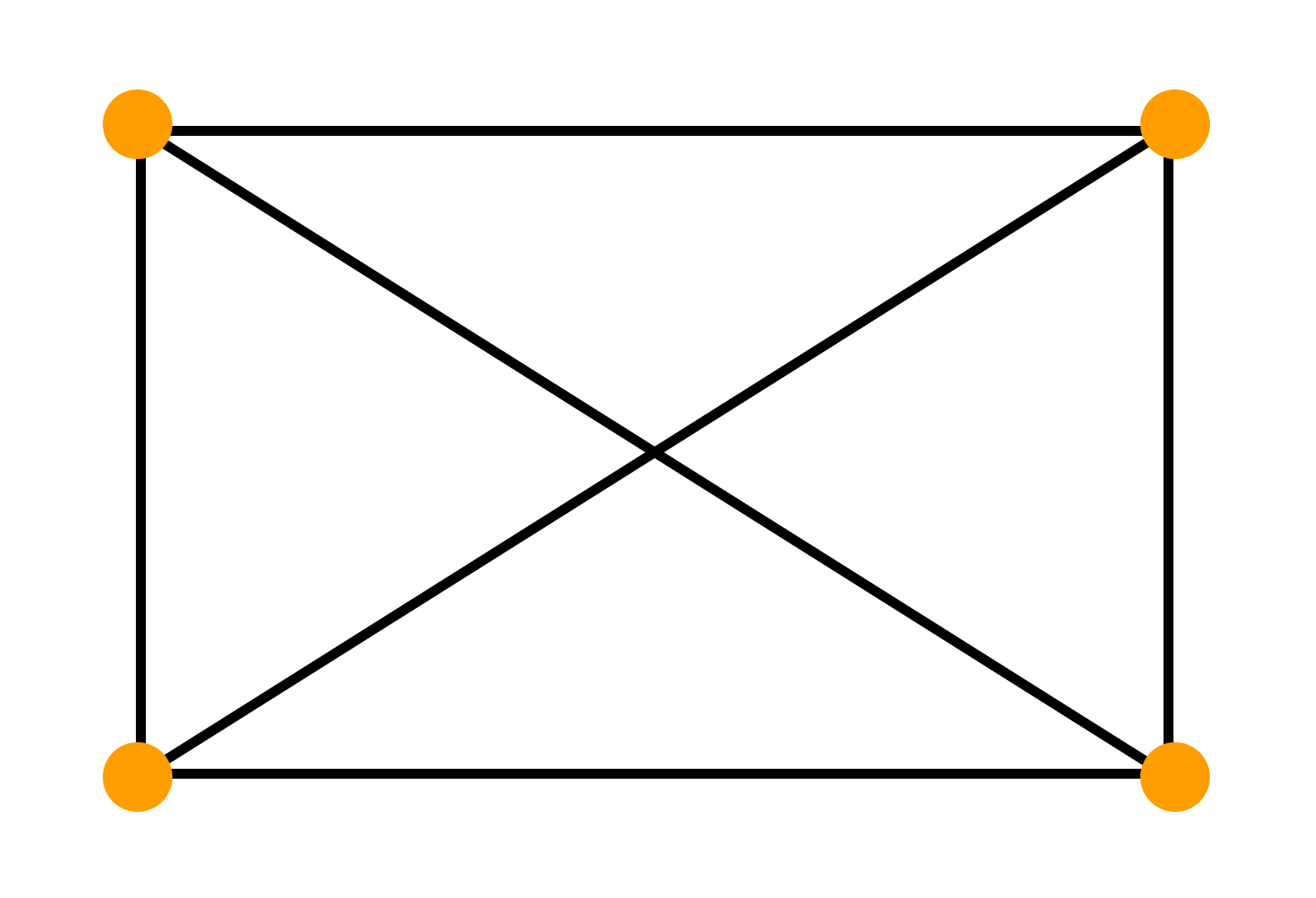

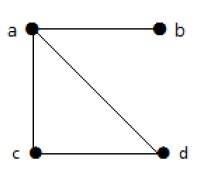

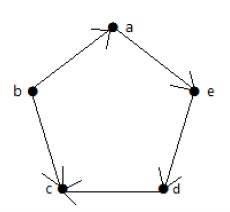

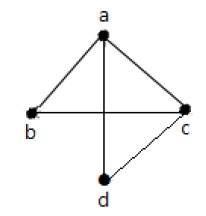

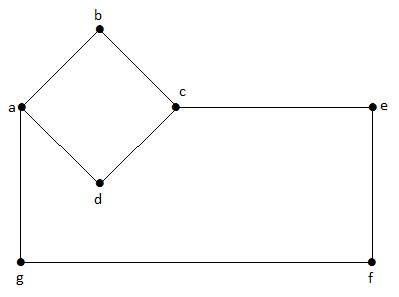

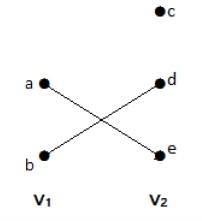

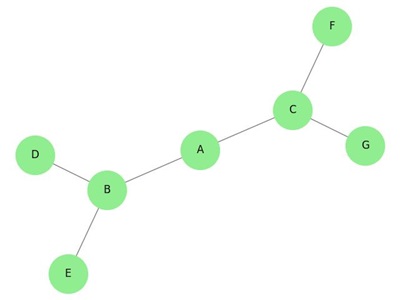

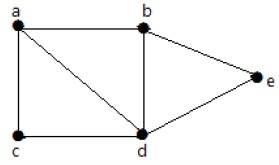

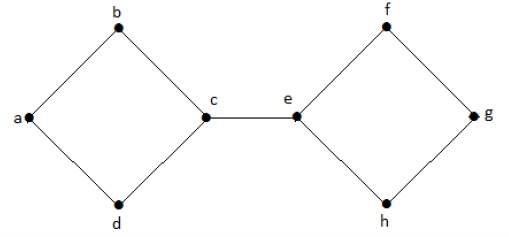

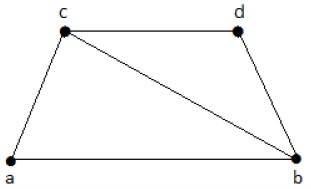

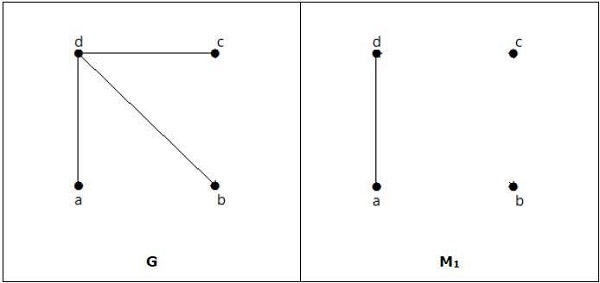

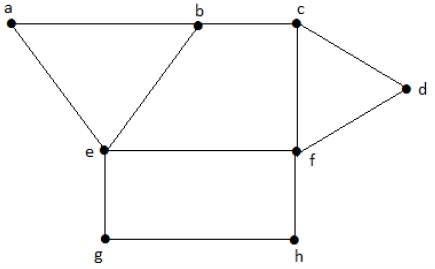

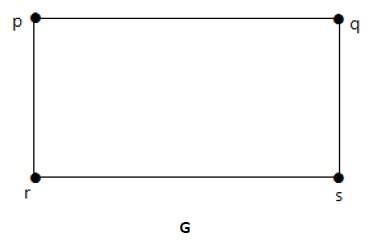

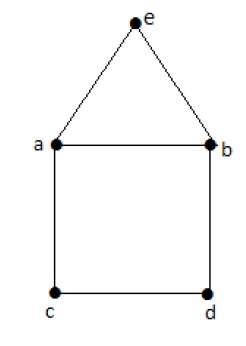

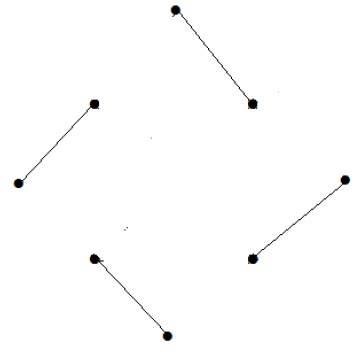

Число знакомых у одних людей может отличаться от числа знакомых у других людей, некоторые могут вовсе не быть знакомы (такие элементы будут точками, не соединёнными ни с какой другой). Так получился граф:

В данном случае точки — это вершины графа, а связки — рёбра графа.

Теория графов не учитывает конкретную природу множеств A и B. Существует большое количество разных задач, при решении которых можно временно забыть о содержании множеств и их элементов. Эта специфика не отражается на ходе решения задачи.

Например, вопрос в задаче стоит так: можно ли из точки A добраться до точки E, если двигаться только по соединяющим точки линиям. Когда задача решена, мы получаем решение, верное для любого содержания, которое можно смоделировать в виде графа.

Не удивительно, что теория графов — один из самых востребованных инструментов при создании искусственного интеллекта: ведь искусственный интеллект может обсудить с человеком вопросы отношений, географии или музыки, решения различных задач.

Графом называется система объектов произвольной природы (вершин) и связок (ребер), соединяющих некоторые пары этих объектов.

Пусть V — (непустое) множество вершин, элементы v ∈ V — вершины. Граф G = G(V) с множеством вершин V есть некоторое семейство пар вида: e = (a, b), где a, b ∈ V, указывающих, какие вершины остаются соединёнными. Каждая пара e = (a, b) — ребро графа. Множество U — множество ребер e графа. Вершины a и b — концевые точки ребра e.

Широкое применение теории графов в компьютерных науках и информационных технологиях можно объяснить понятием графа как структуры данных. В компьютерных науках и информационных технологиях граф можно описать, как нелинейную структуру данных.

Линейные структуры данных особенны тем, что связывают элементы отношениями по типу «простого соседства». Линейными структурами данных можно назвать массивы, таблицы, списки, очереди, стеки, строки. В нелинейных структурах данных элементы располагаются на различных уровнях иерархии и подразделяются на три вида: исходные, порожденные и подобные.

Курсы обучения математике помогут подтянуть оценки, подготовиться к контрольным, ВПР и экзаменам.

Получай лайфхаки, статьи, видео и чек-листы по обучению на почту

Узнай, какие профессии будущего тебе подойдут

Пройди тест — и мы покажем, кем ты можешь стать, а ещё пришлём подробный гайд, как реализовать себя уже сейчас

Основные понятия теории графов

Граф — это геометрическая фигура, которая состоит из точек и линий, которые их соединяют. Точки называют вершинами графа, а линии — ребрами.

- Два ребра называются смежными, если у них есть общая вершина.

- Два ребра называются кратными, если они соединяют одну и ту же пару вершин.

- Ребро называется петлей, если его концы совпадают.

- Степенью вершины называют количество ребер, для которых она является концевой (при этом петли считают дважды).

- Вершина называется изолированной, если она не является концом ни для одного ребра.

- Вершина называется висячей, если из неё выходит ровно одно ребро.

- Граф без кратных ребер и петель называется обыкновенным.

Лемма о рукопожатиях

В любом графе сумма степеней всех вершин равна удвоенному числу ребер.

Доказательство леммы о рукопожатиях

Если ребро соединяет две различные вершины графа, то при подсчете суммы степеней вершин мы учтем это ребро дважды.

Если же ребро является петлей — при подсчете суммы степеней вершин мы также учтем его дважды (по определению степени вершины).

Из леммы о рукопожатиях следует: в любом графе число вершин нечетной степени — четно.

Пример 1. В классе 30 человек. Может ли быть так, что у 9 из них есть 3 друга в этом классе, у 11 — 4 друга, а у 10 — 5 друзей? Учесть, что дружбы взаимные.

Как рассуждаем:

Если бы это было возможно, то можно было бы нарисовать граф с 30 вершинами, 9 из которых имели бы степень 3, 11 — со степенью 4, 10 — со степенью 5. Однако у такого графа 19 нечетных вершин, что противоречит следствию из леммы о рукопожатиях.

Пример 2. Каждый из 102 учеников одной школы знаком не менее чем с 68 другими. Доказать, что среди них найдутся четверо ребят с одинаковым числом знакомых.

Как рассуждаем:

Сначала предположим противоположное. Тогда для каждого числа от 68 до 101 есть не более трех человек с таким числом знакомых. С другой стороны, у нас есть ровно 34 натуральных числа, начиная с 68 и заканчивая 101, а 102 = 34 * 3.

Это значит, что для каждого числа от 68 до 101 есть ровно три человека, имеющих такое число знакомых. Но тогда количество людей, имеющих нечетное число знакомых, нечетно. Противоречие.

Путь и цепь в графе

Путем или цепью в графе называют конечную последовательность вершин, в которой каждая вершина (кроме последней) соединена со следующей в последовательности вершин ребром.

Циклом называют путь, в котором первая и последняя вершины совпадают.

Путь или цикл называют простым, если ребра в нем не повторяются.

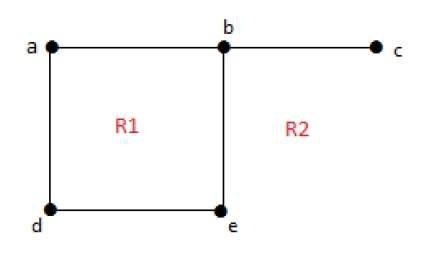

Если в графе любые две вершины соединены путем, то такой граф называется связным.

Можно рассмотреть такое подмножество вершин графа, что каждые две вершины этого подмножества соединены путем, а никакая другая вершина не соединена ни с какой вершиной этого подмножества.

Каждое такое подмножество, вместе со всеми ребрами исходного графа, соединяющими вершины этого подмножества, называется компонентой связности.

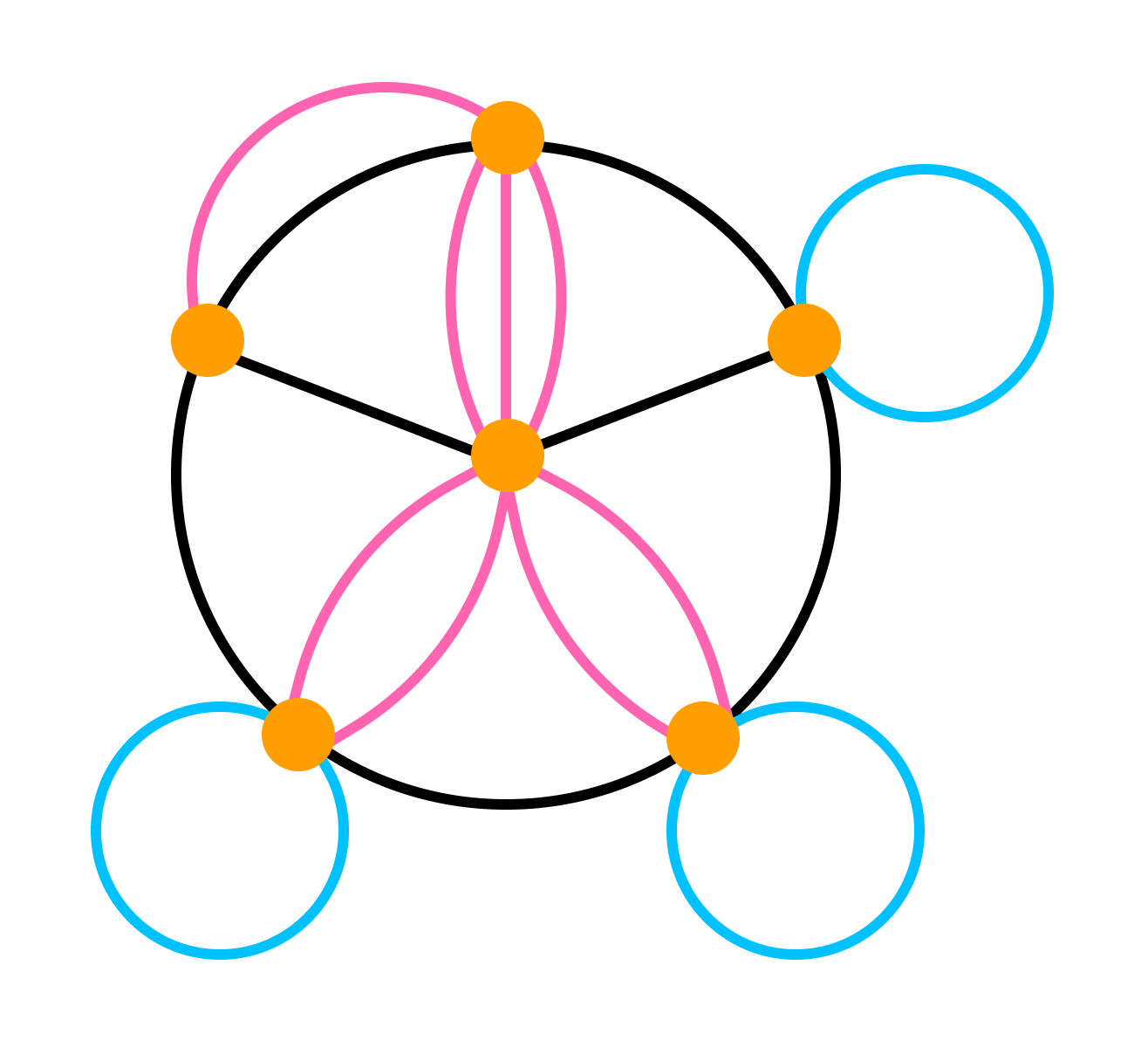

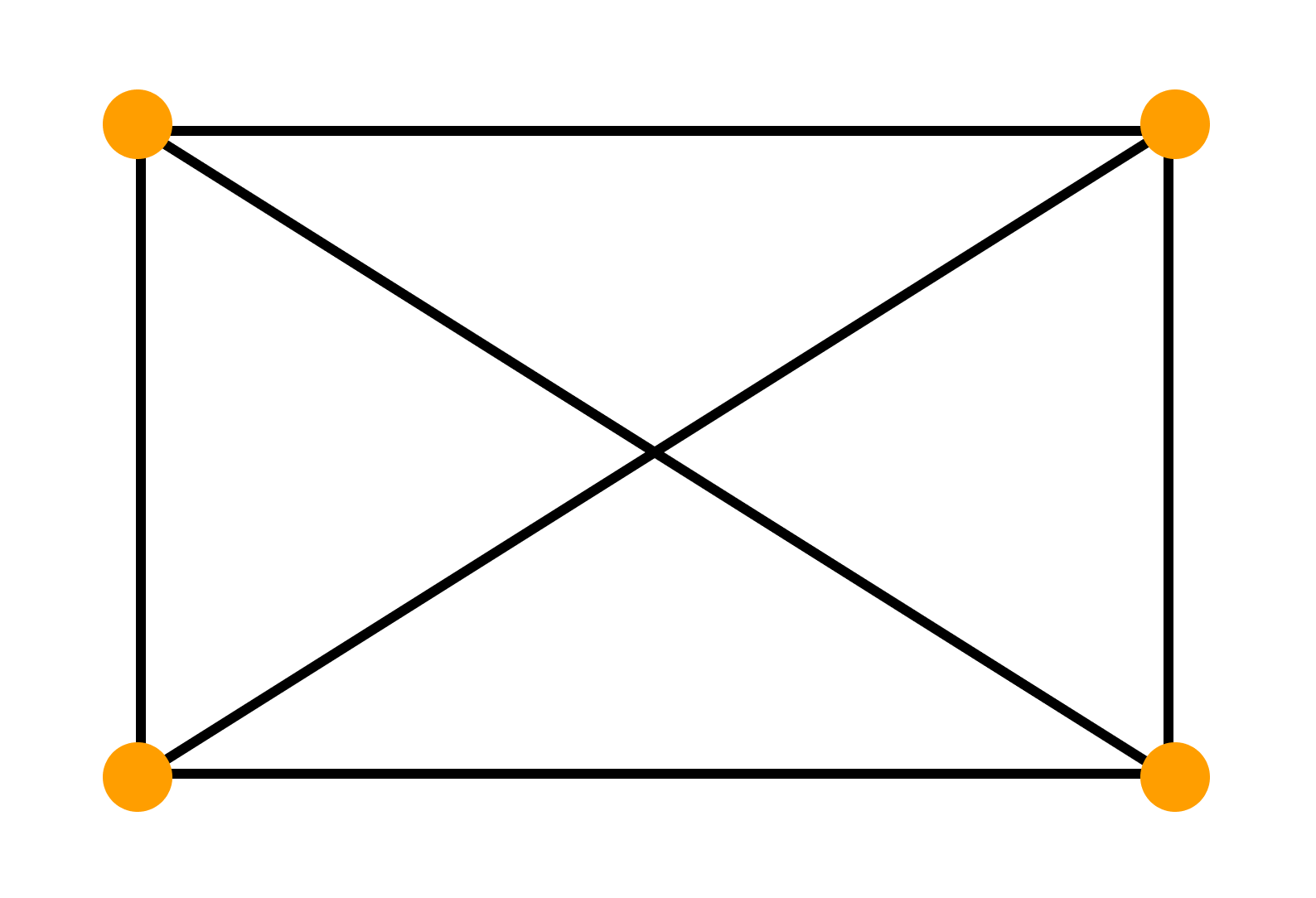

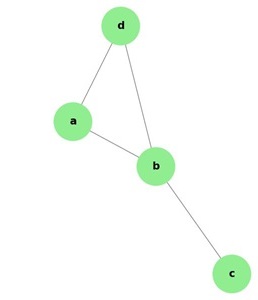

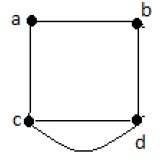

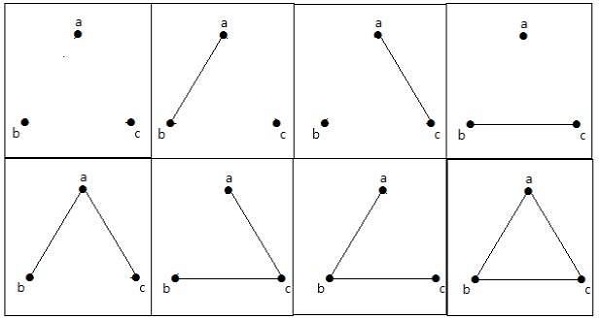

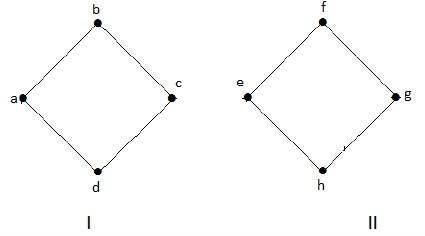

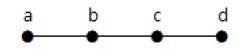

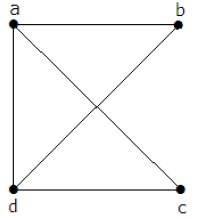

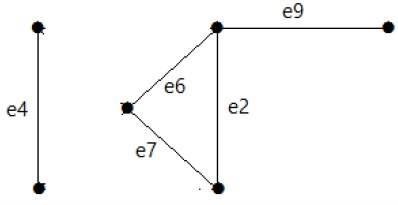

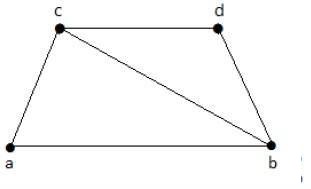

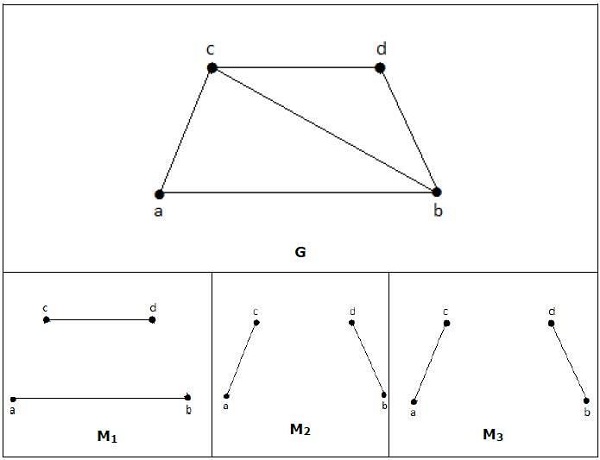

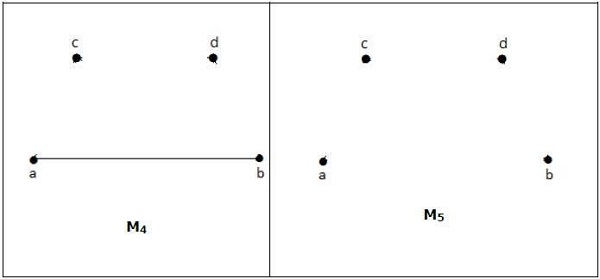

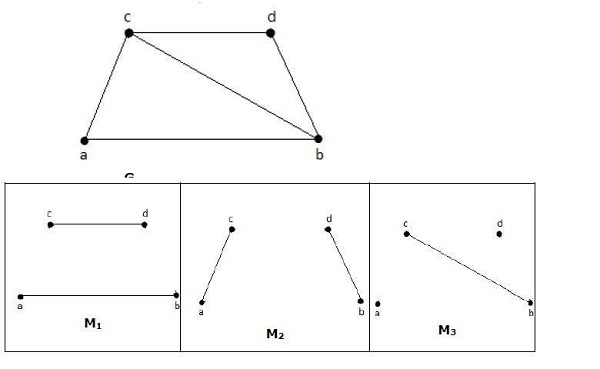

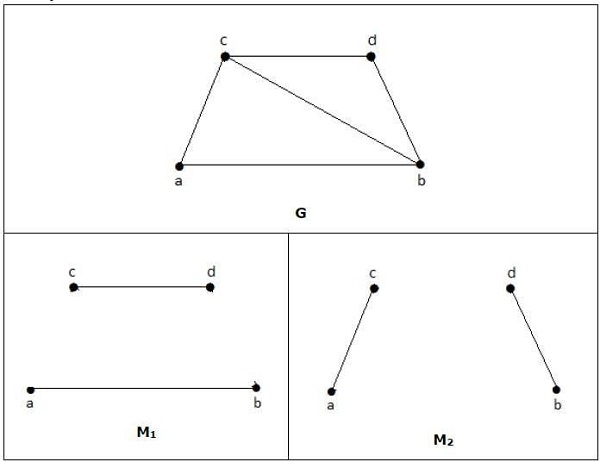

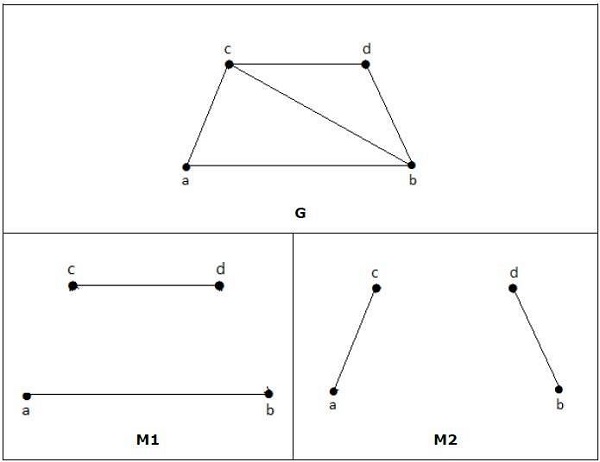

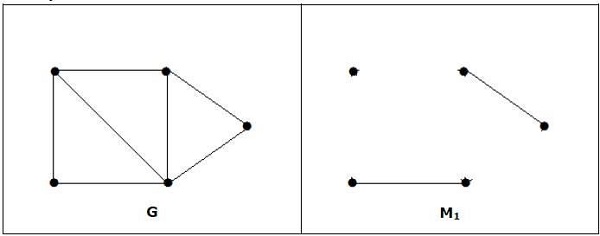

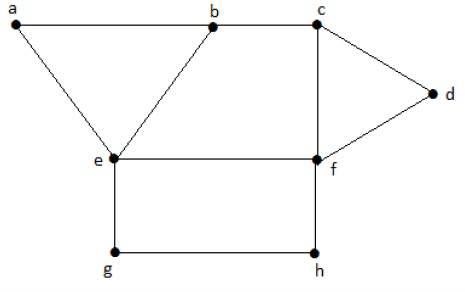

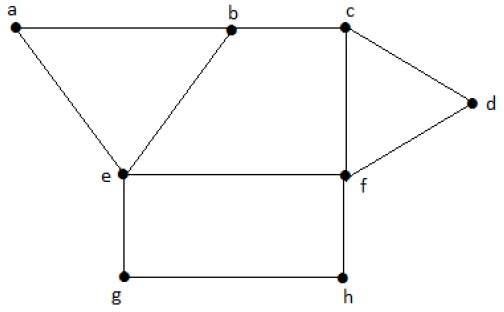

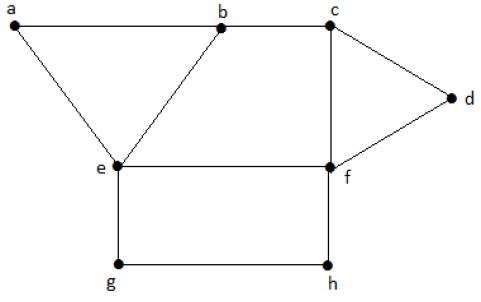

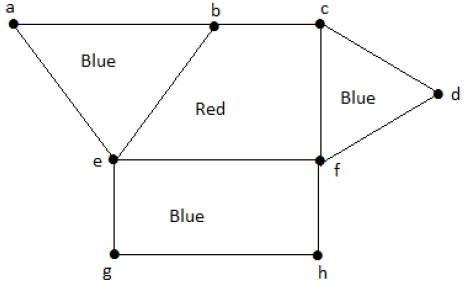

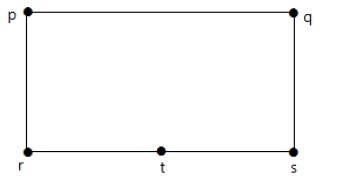

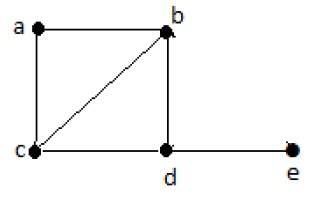

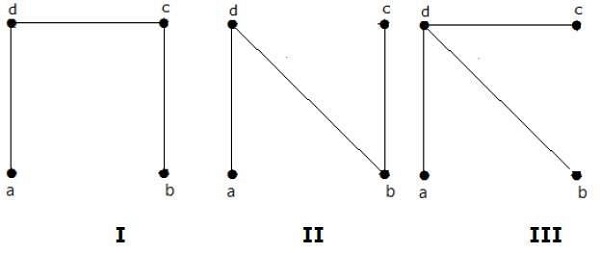

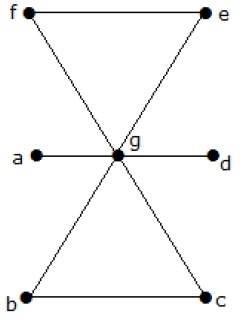

Один и тот же граф можно нарисовать разными способами. Вот, например, два изображения одного и того же графа, которые различаются кривизной:

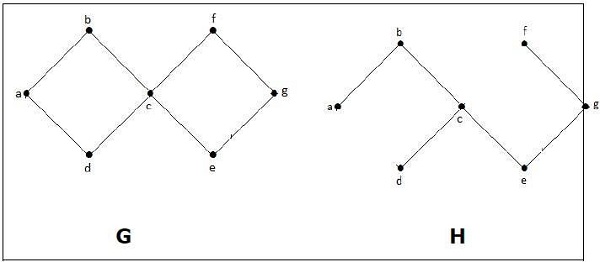

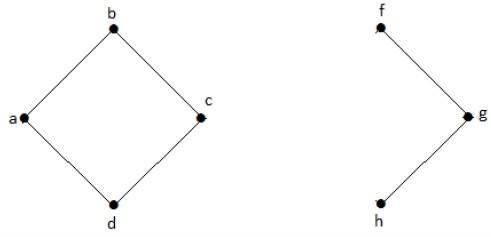

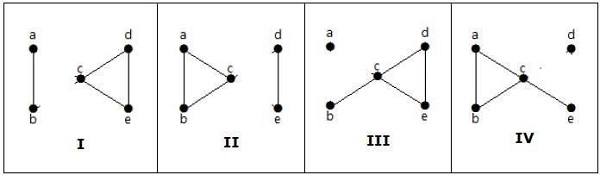

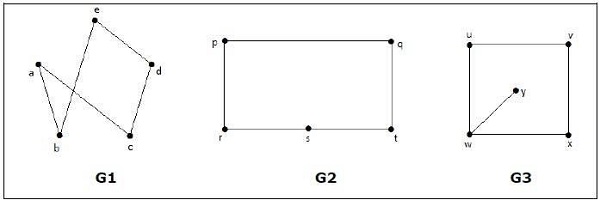

Два графа называются изоморфными, если у них поровну вершин. При этом вершины каждого графа можно занумеровать числами так, чтобы вершины первого графа были соединены ребром тогда и только тогда, когда соединены ребром соответствующие занумерованные теми же числами вершины второго графа.

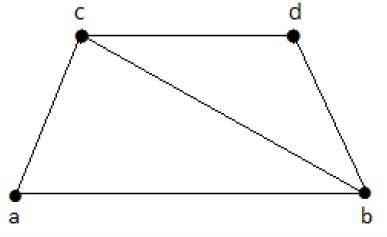

Граф H, множество вершин V’ которого является подмножеством вершин V данного графа G и множество рёбер которого является подмножеством рёбер графа G соединяющими вершины из V’ называется подграфом графа G.

Визуализация графовых моделей

Визуализация — это процесс преобразования больших и сложных видов абстрактной информации в интуитивно-понятную визуальную форму. Другими словами, когда мы рисуем то, что нам непонятно — и сразу все встает на свои места.

Графы — и есть помощники в этом деле. Они помогают представить любую информацию, которую можно промоделировать в виде объектов и связей между ними.

Граф можно нарисовать на плоскости или в трехмерном пространстве. Его можно изобразить целиком, частично или иерархически.

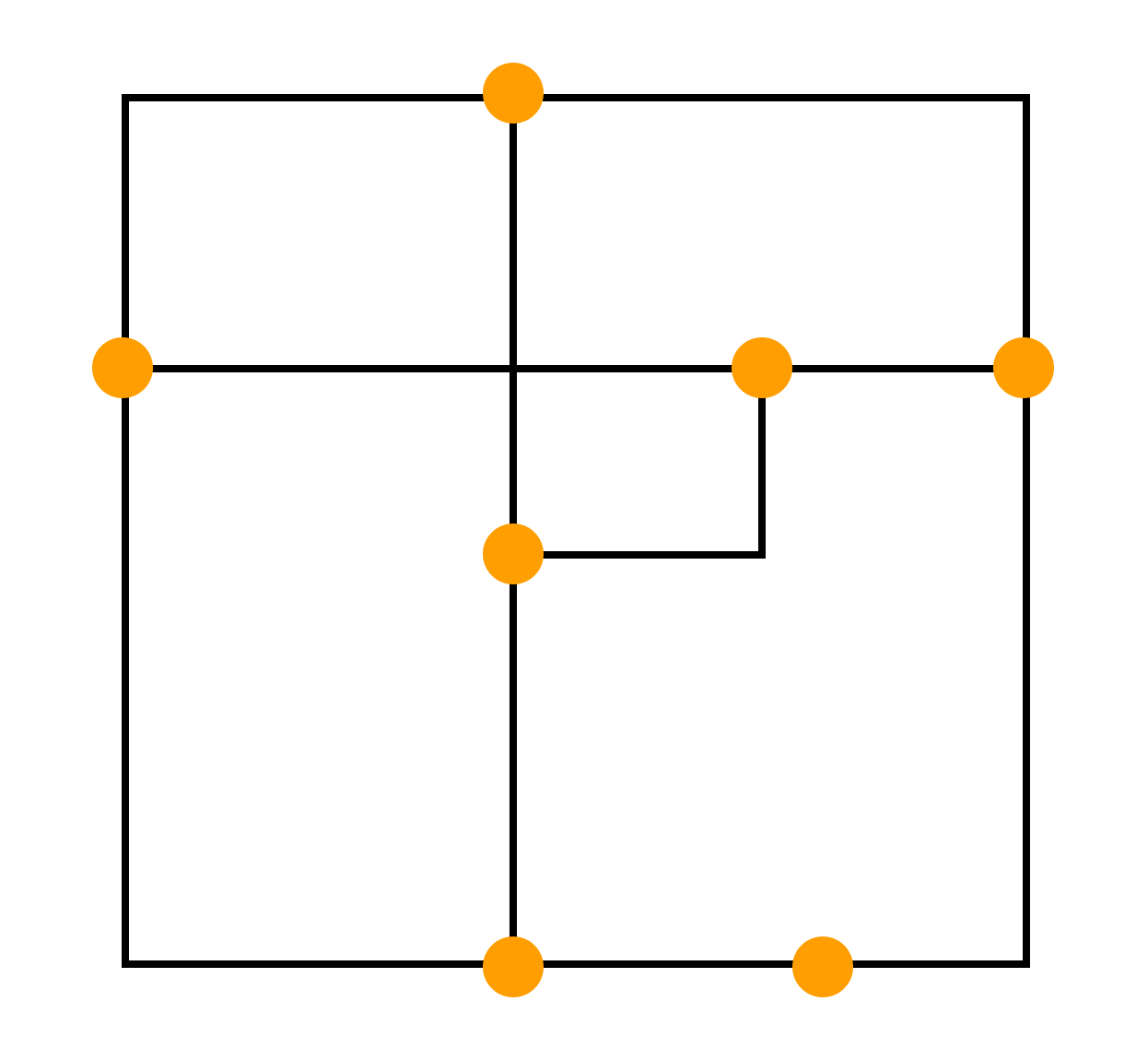

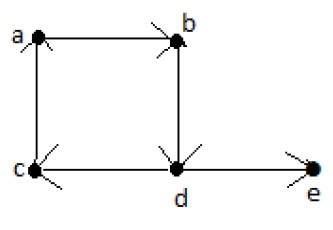

Изобразительное соглашение — одно из основных правил, которому должно удовлетворять изображение графа, чтобы быть допустимым. Например, при изображении блок-схемы программы можно использовать соглашение о том, что все вершины должны изображаться прямоугольниками, а дуги — ломаными линиями с вертикальными и горизонтальными звеньями. При этом, конкретный вид соглашения может быть достаточно сложен и включать много деталей.

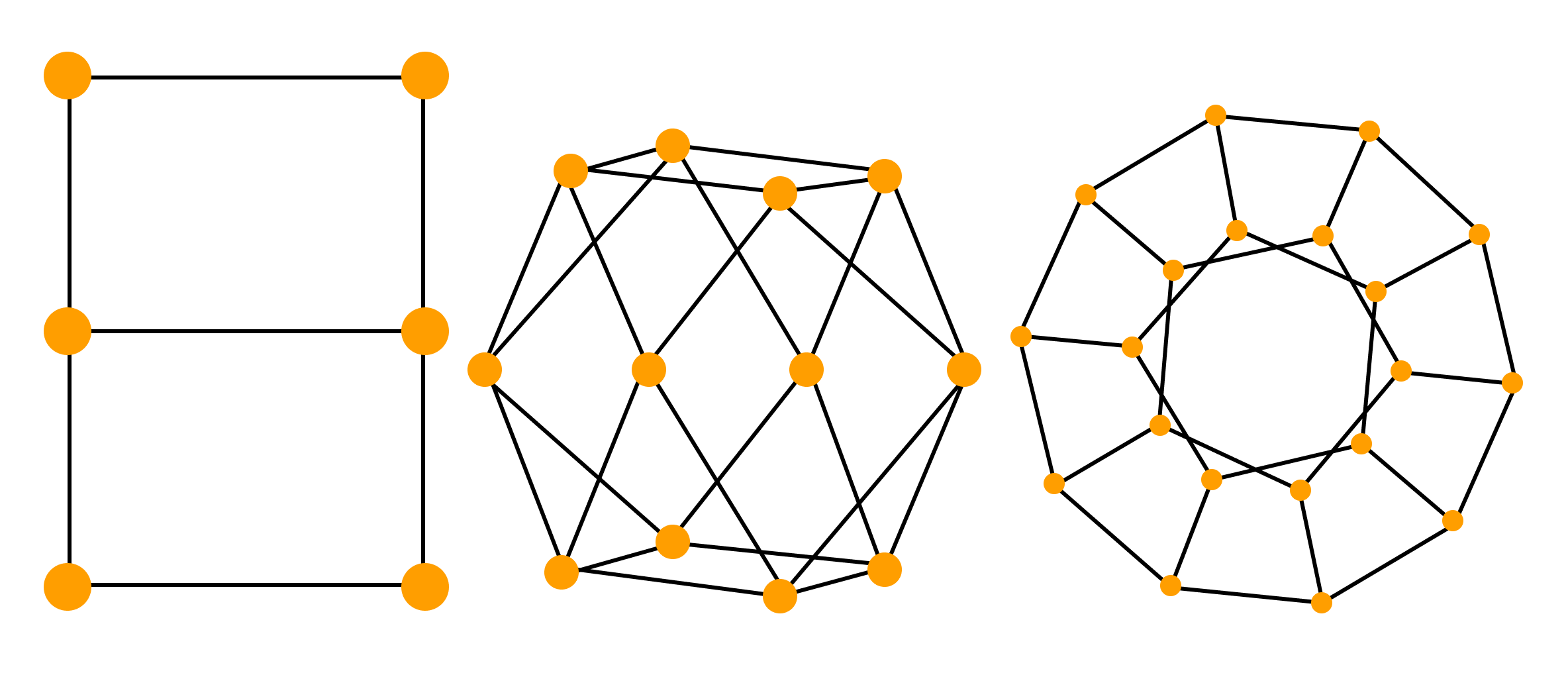

Виды изобразительных соглашений:

- полилинейное изображение — каждое ребро графа рисуют в виде ломаной линии

- прямолинейное изображение — каждое ребро представляют с помощью отрезка прямой

- ортогональное изображение — каждое ребро графа изображается в виде ломаной линии, состоящей из чередующихся горизонтальных и вертикальных сегментов

- сетчатое изображение — все вершины, а также все точки пересечения и сгибы ребер имеют целочисленные координаты. То есть находятся в узлах координатной сетки, образованной прямыми, параллельными координатным осям и пересекающими их в точках с целочисленными координатами

- плоское изображение предполагает отсутствие точек пересечения у линий, изображающих ребра.

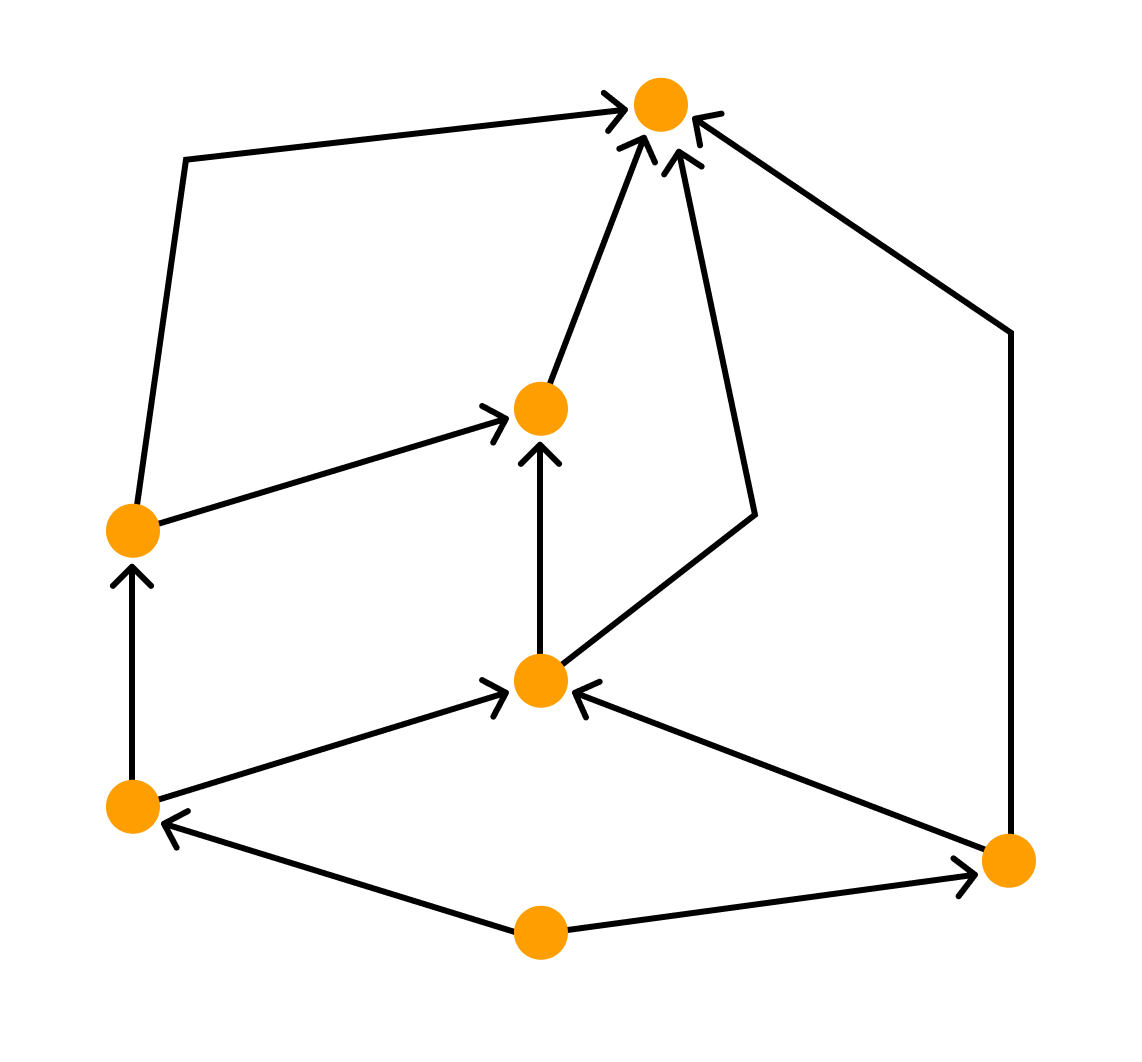

- восходящее или нисходящее изображение имеет смысл по отношению к ациклическому орграфу и предполагает, что каждая дуга изображается ориентированной линией, координаты точек которой монотонно изменяются в направлении снизу вверх или сверху вниз, а также слева направо.

- Деревом называется связный граф не содержащий простых циклов.

- Деревом называется связный граф, содержащий n вершин и n — 1 ребро.

- Деревом называется связный граф, который при удалении любого ребра перестает быть связным.

- Деревом называется граф, в котором любые две вершины соединены ровно одним простым путем.

- одна вершина, у которой нет предшественников, определяет время начала работы

- одна вершина без последователей соответствует моменту завершения комплекса работ.

Виды графов

Виды графов можно определять по тому, как их построили или по свойствам вершин или ребер.

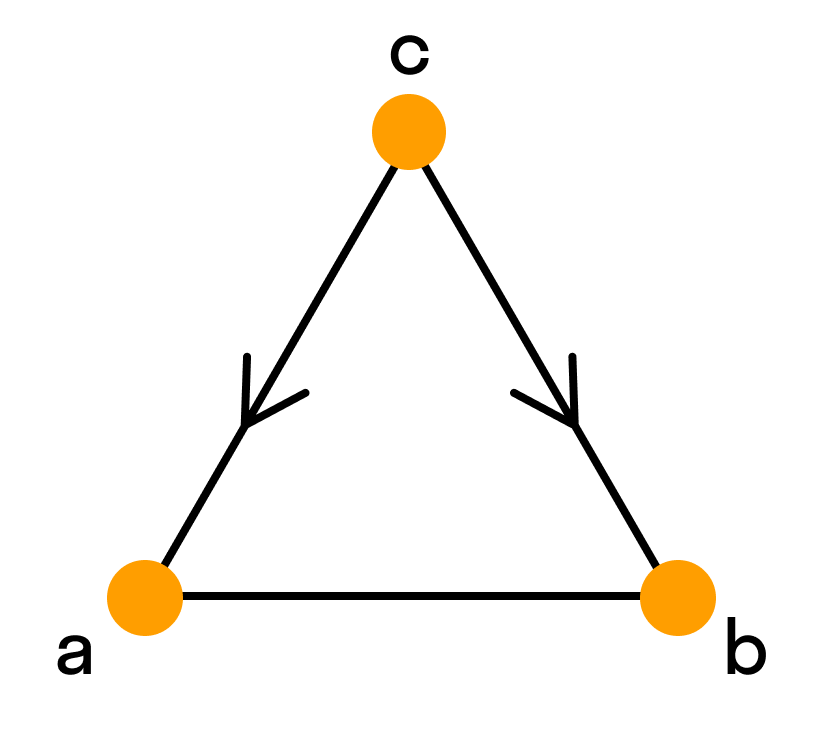

Ориентированные и неориентированные графы

Графы, в которых все ребра являются звеньями, то есть порядок двух концов ребра графа не существенен, называются неориентированными.

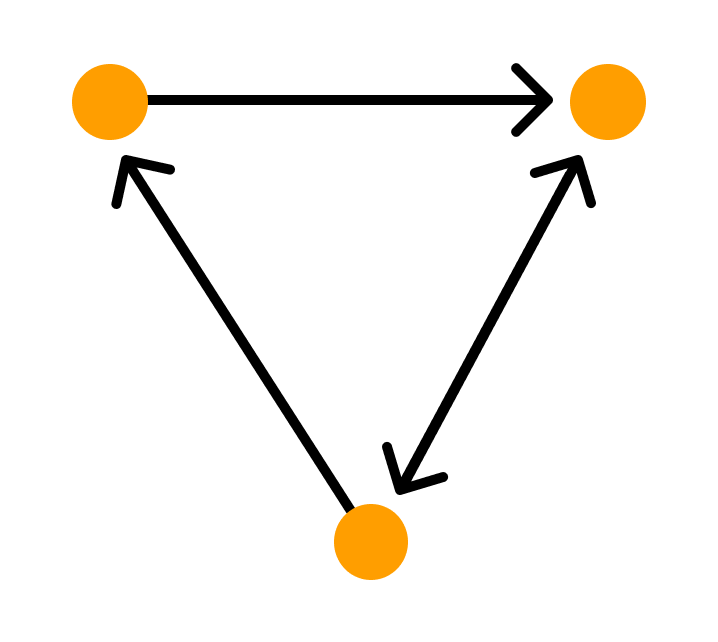

Графы, в которых все ребра являются дугами, то есть порядок двух концов ребра графа существенен, называются ориентированными графами или орграфами.

Неориентированный граф можно представить в виде ориентированного графа, если каждое его звено заменить на две дуги с противоположным направлением.

Графы с петлями, смешанные графы, пустые графы, мультиграфы, обыкновенные графы, полные графы

Если граф содержит петли — это обстоятельство важно озвучивать и добавлять к основной характеристике графа уточнение «с петлями». Если граф не содержит петель, то добавляют «без петель».

Смешанным называют граф, в котором есть ребра хотя бы двух из упомянутых трех разновидностей (звенья, дуги, петли).

Пустой граф — это тот, что состоит только из голых вершин.

Мультиграфом — такой граф, в котором пары вершин соединены более, чем одним ребром. То есть есть кратные рёбра, но нет петель.

Граф без дуг, то есть неориентированный, без петель и кратных ребер называется обыкновенным.

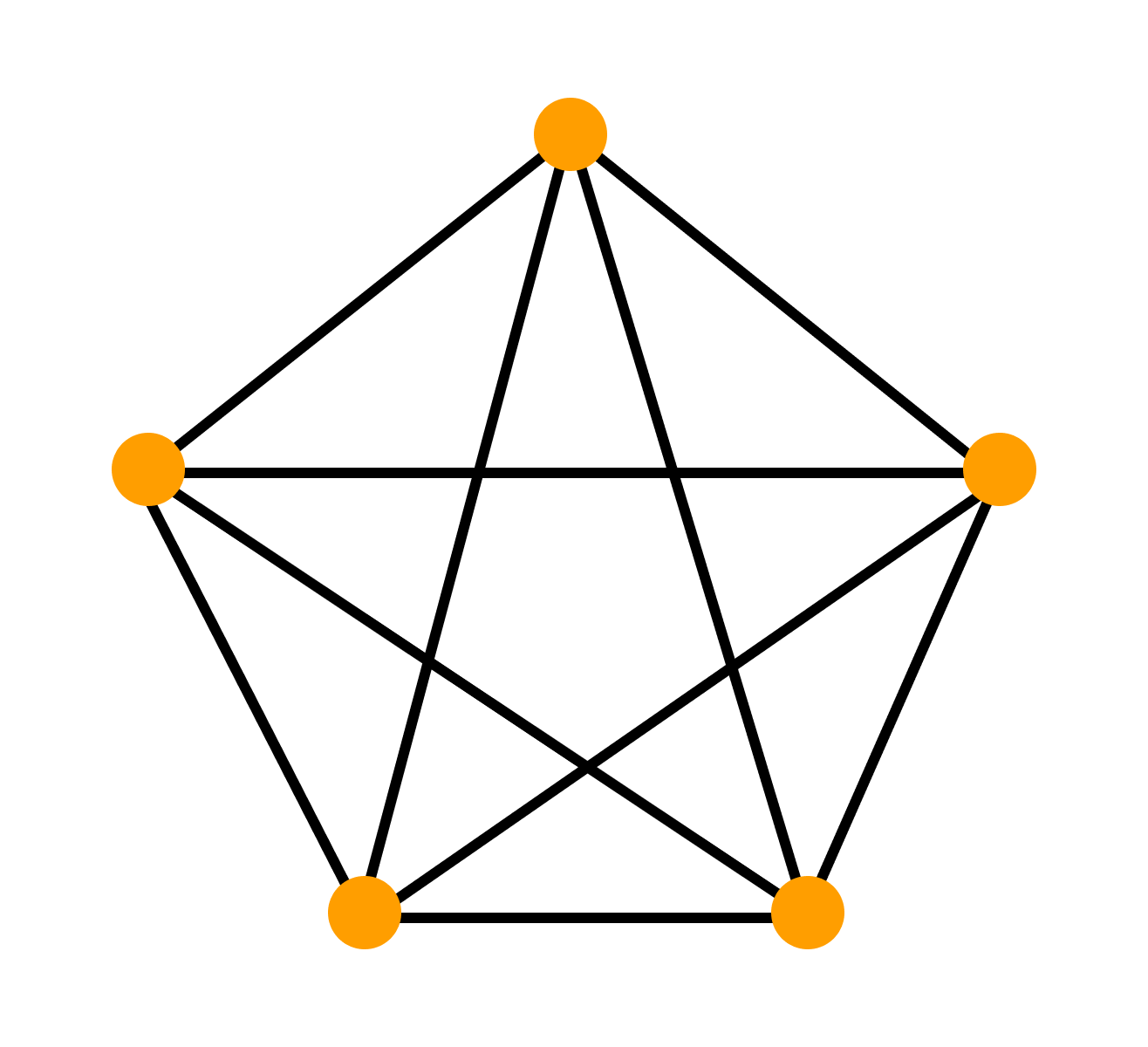

Граф называют полным, если он содержит все возможные для этого типа рёбра при неизменном множестве вершин. Так, в полном обыкновенном графе каждая пара различных вершин соединена ровно одним звеном.

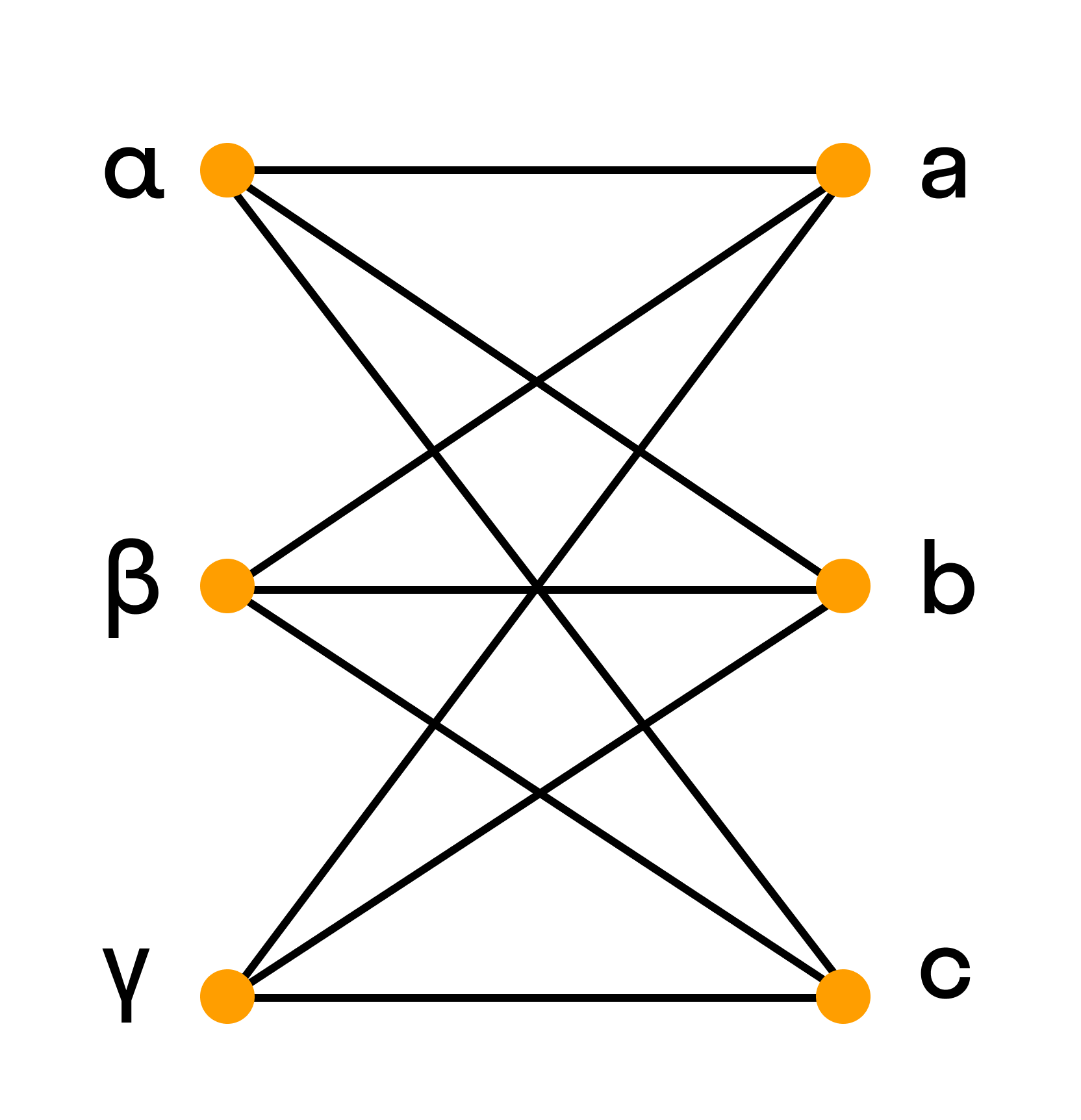

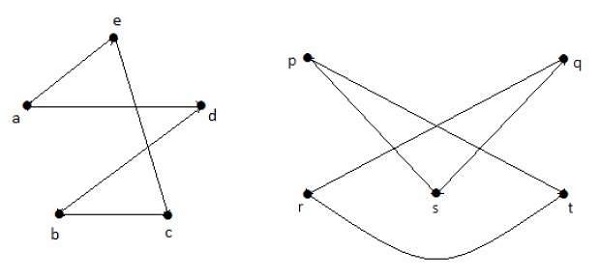

Двудольный граф

Граф называется двудольным, если множество его вершин можно разбить на два подмножества так, чтобы никакое ребро не соединяло вершины одного и того же подмножества.

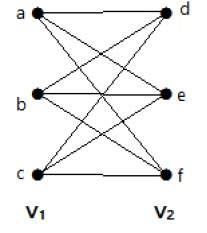

Например, полный двудольный граф состоит из двух множеств вершин и из всевозможных звеньев, которые соединяют вершины одного множества с вершинами другого множества.

Эйлеров граф

Эйлеров граф отличен тем, что в нем можно обойти все вершины и при этом пройти одно ребро только один раз. В нём каждая вершина должна иметь только чётное число рёбер.

Пример. Является ли полный граф с одинаковым числом n рёбер, которым инцидентна каждая вершина, эйлеровым графом?

Ответ. Если n — нечётное число, то каждая вершина инцидентна n — 1 ребрам. В таком случае наш граф — эйлеровый.

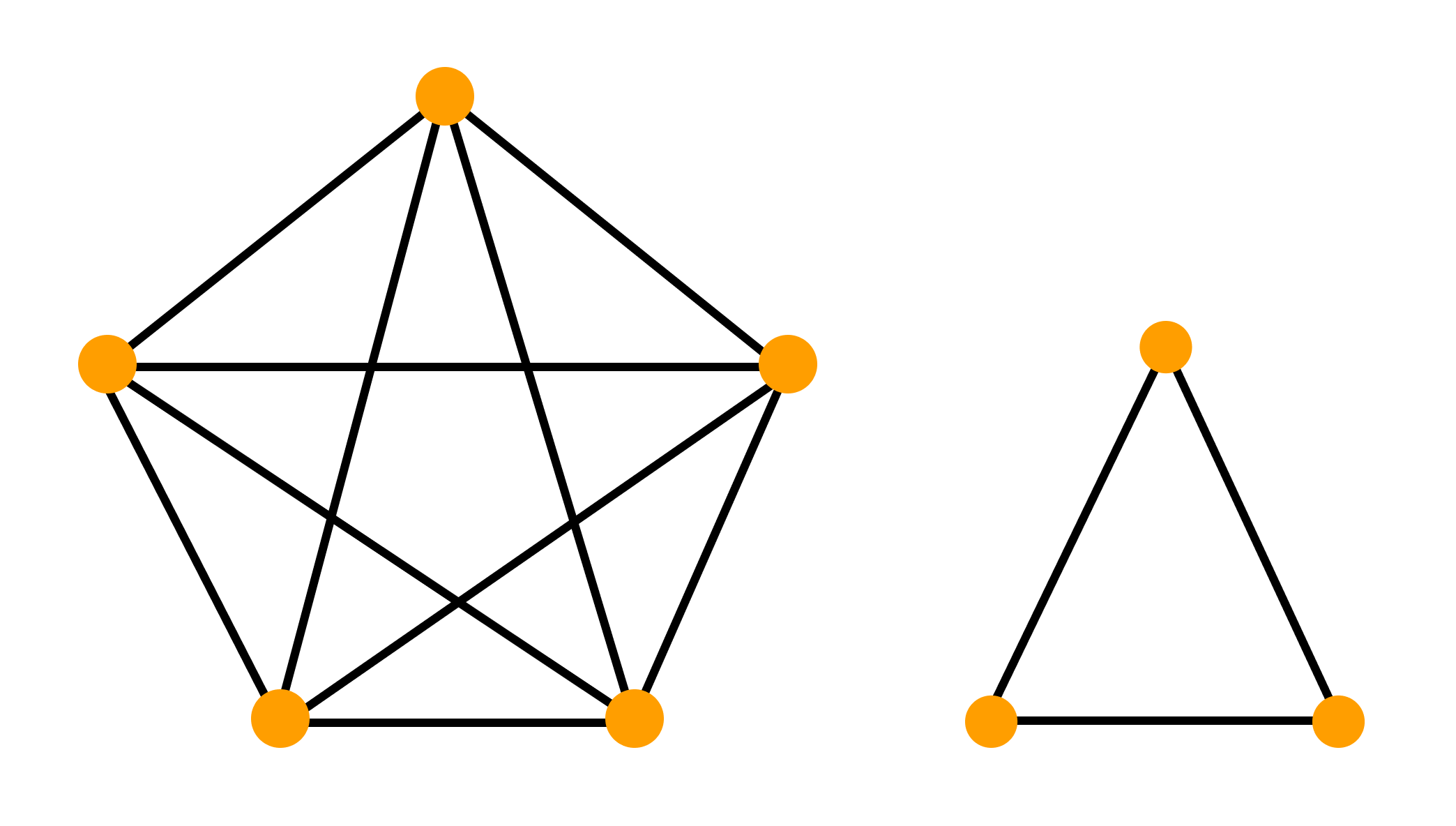

Регулярный граф

Регулярным графом называется связный граф, все вершины которого имеют одинаковую степень k.

Число вершин регулярного графа k-й степени не может быть меньше k + 1. У регулярного графа нечётной степени может быть лишь чётное число вершин.

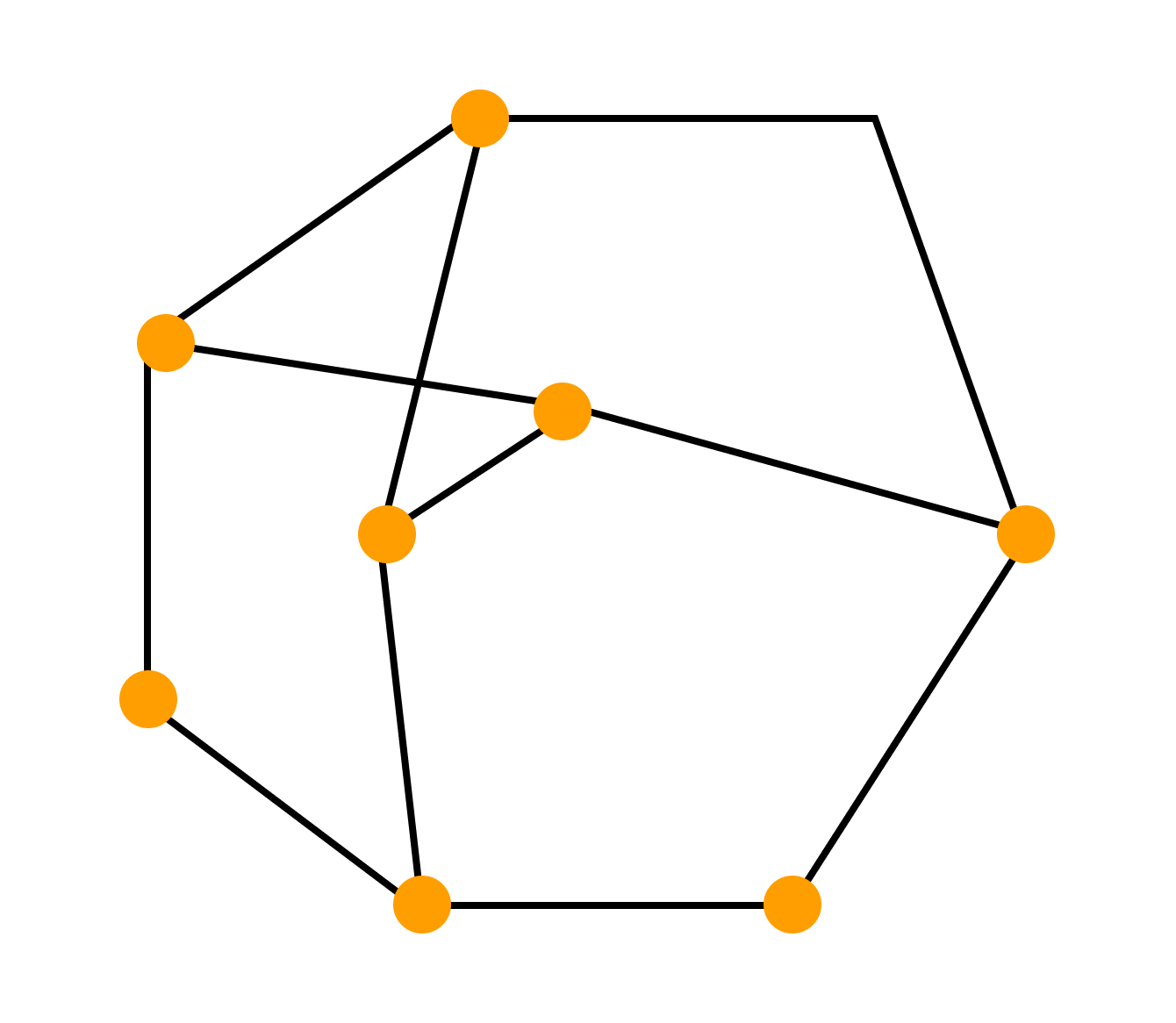

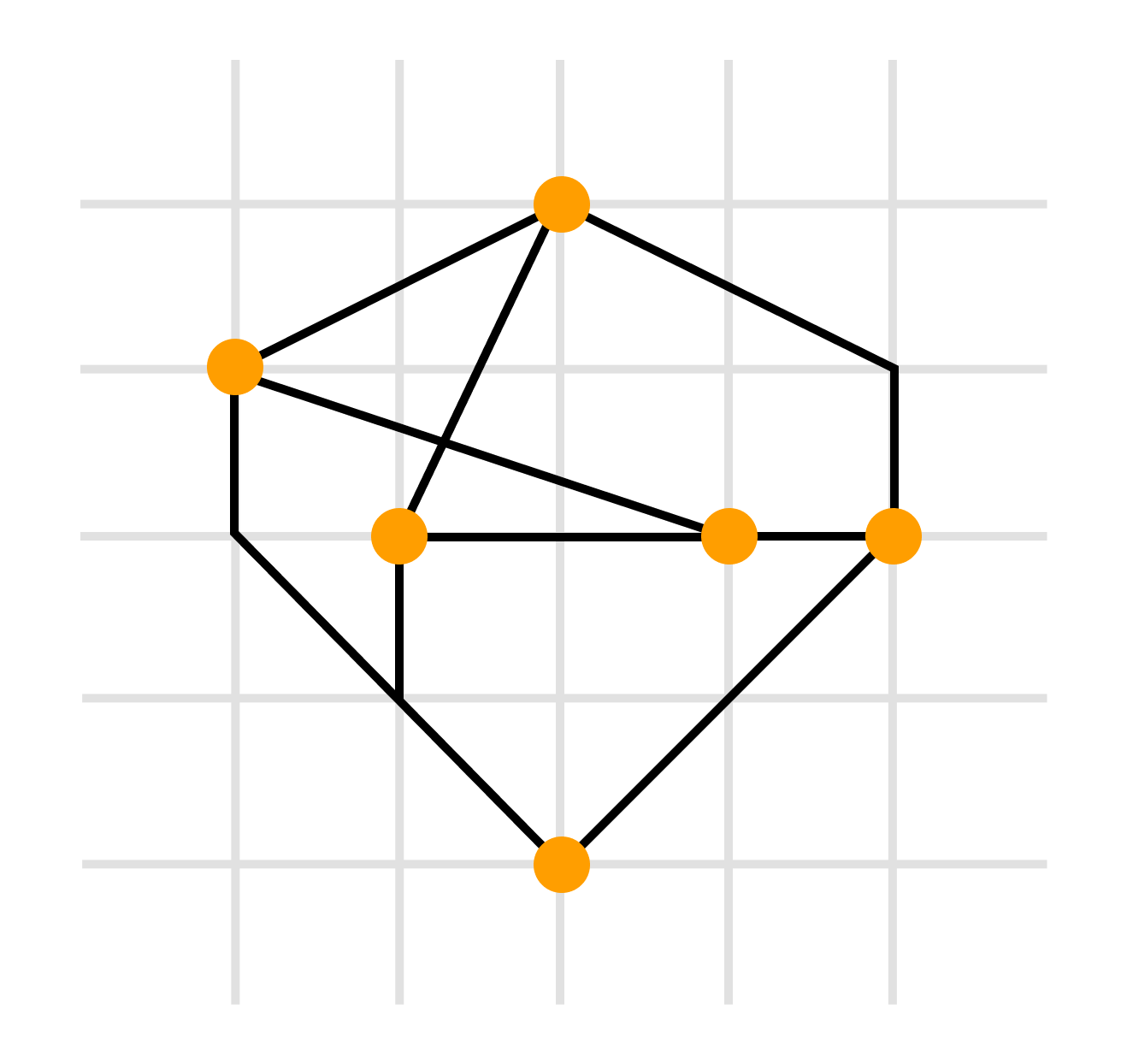

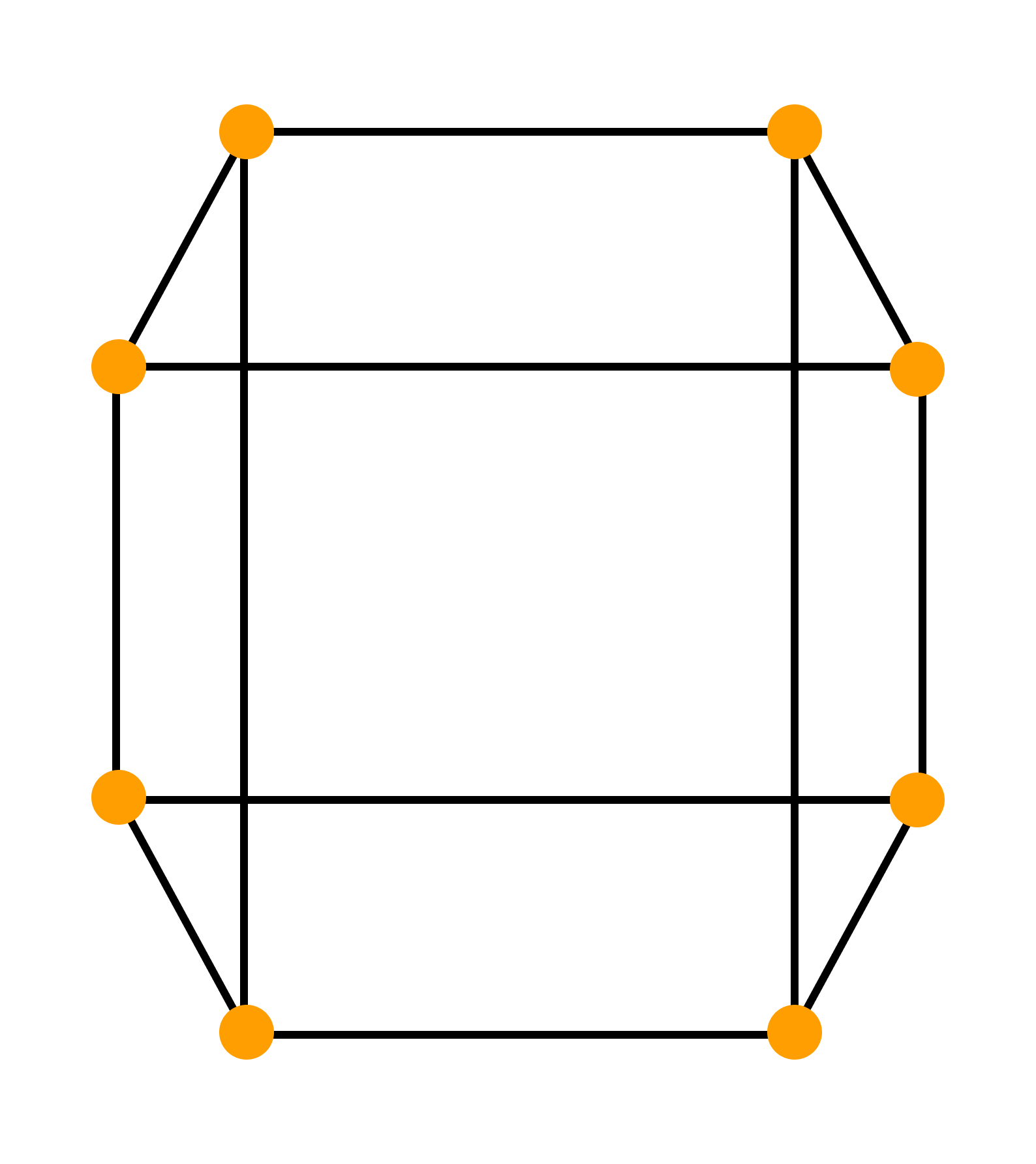

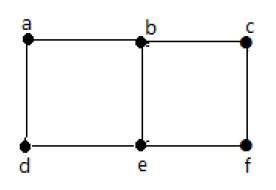

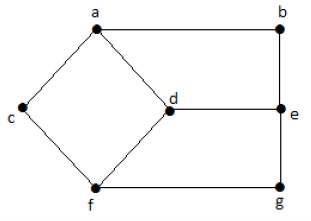

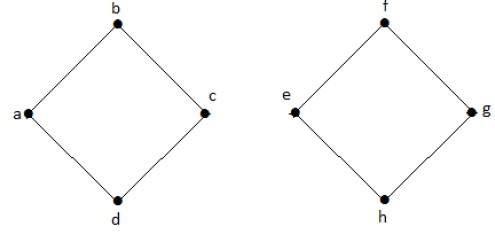

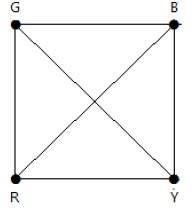

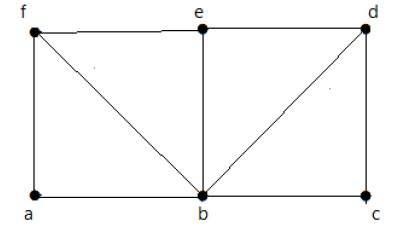

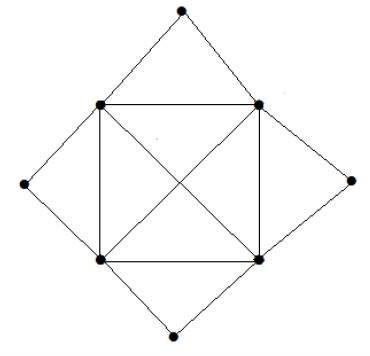

Пример. Построить регулярный граф, в котором самый короткий цикл имеет длину 4.

Рассуждаем так:

Чтобы длина цикла соответствовала заданному условию, нужно чтобы число вершин графа было кратно четырем. Если число вершин равно четырём — получится регулярный граф, в котором самый короткий цикл имеет длину 3.

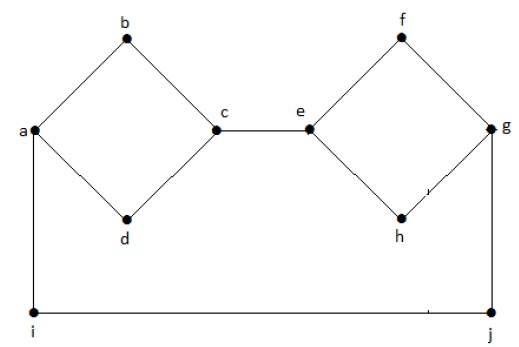

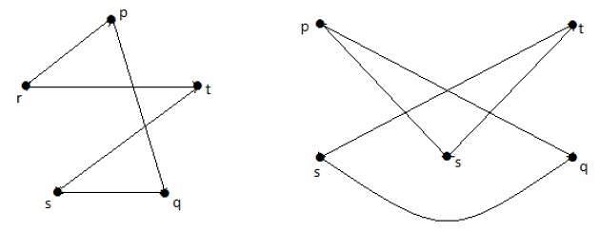

Увеличим число вершин до восьми (следующее кратное четырем число). Соединим вершины ребрами так, чтобы степени вершин были равны трём. Получаем следующий граф, удовлетворяющий условиям задачи:

Гамильтонов граф

Гамильтоновым графом называется граф, содержащий гамильтонов цикл.

Гамильтоновым циклом называется простой цикл, который проходит через все вершины рассматриваемого графа.

Говоря проще, гамильтонов граф — это такой граф, в котором можно обойти все вершины, и каждая вершина при обходе повторяется лишь один раз.

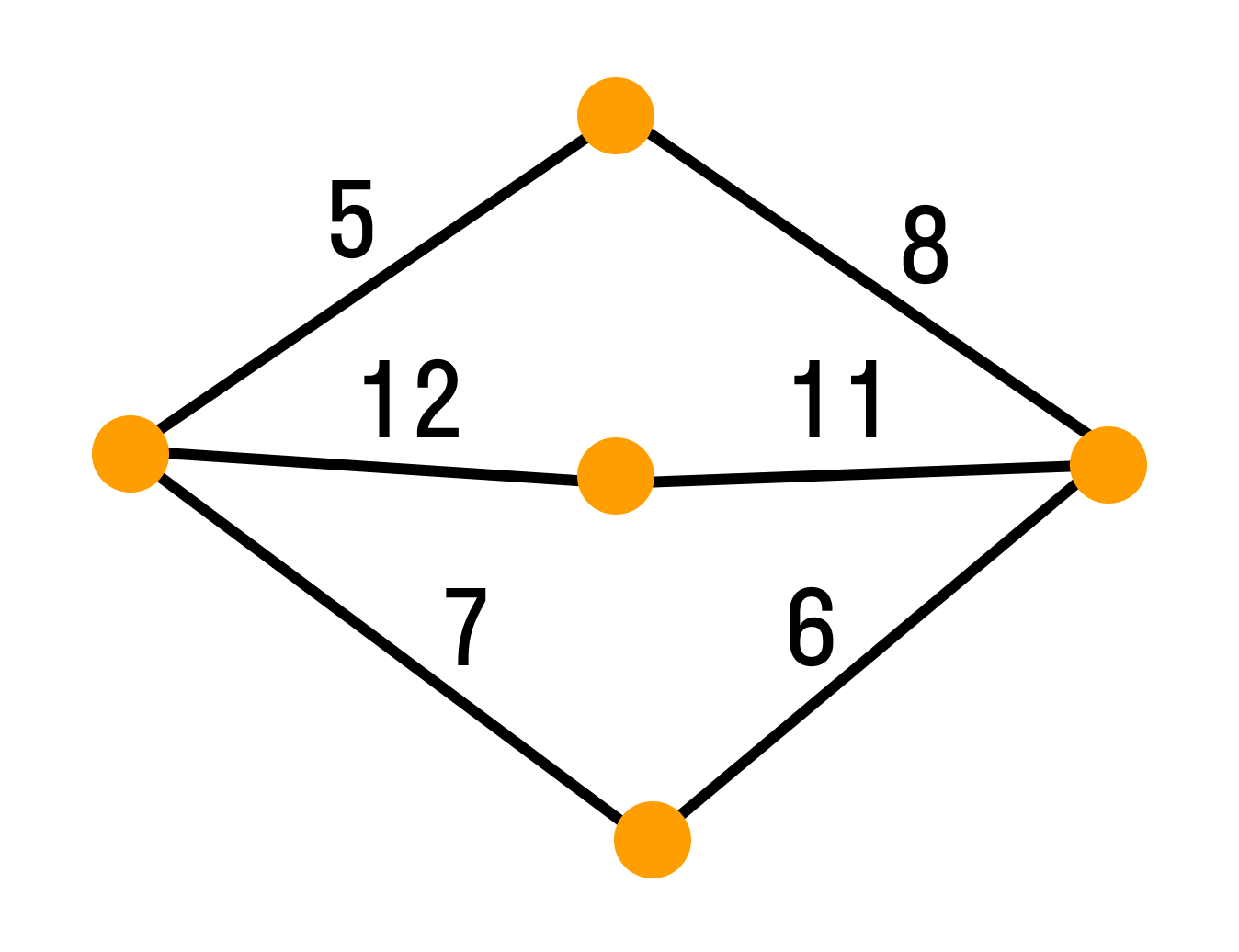

Взвешенный граф

Взвешенным графом называется граф, вершинам и/или ребрам которого присвоены «весы» — обычно некоторые числа. Пример взвешенного графа — транспортная сеть, в которой ребрам присвоены весы: они показывают стоимость перевозки груза по ребру и пропускные способности дуг.

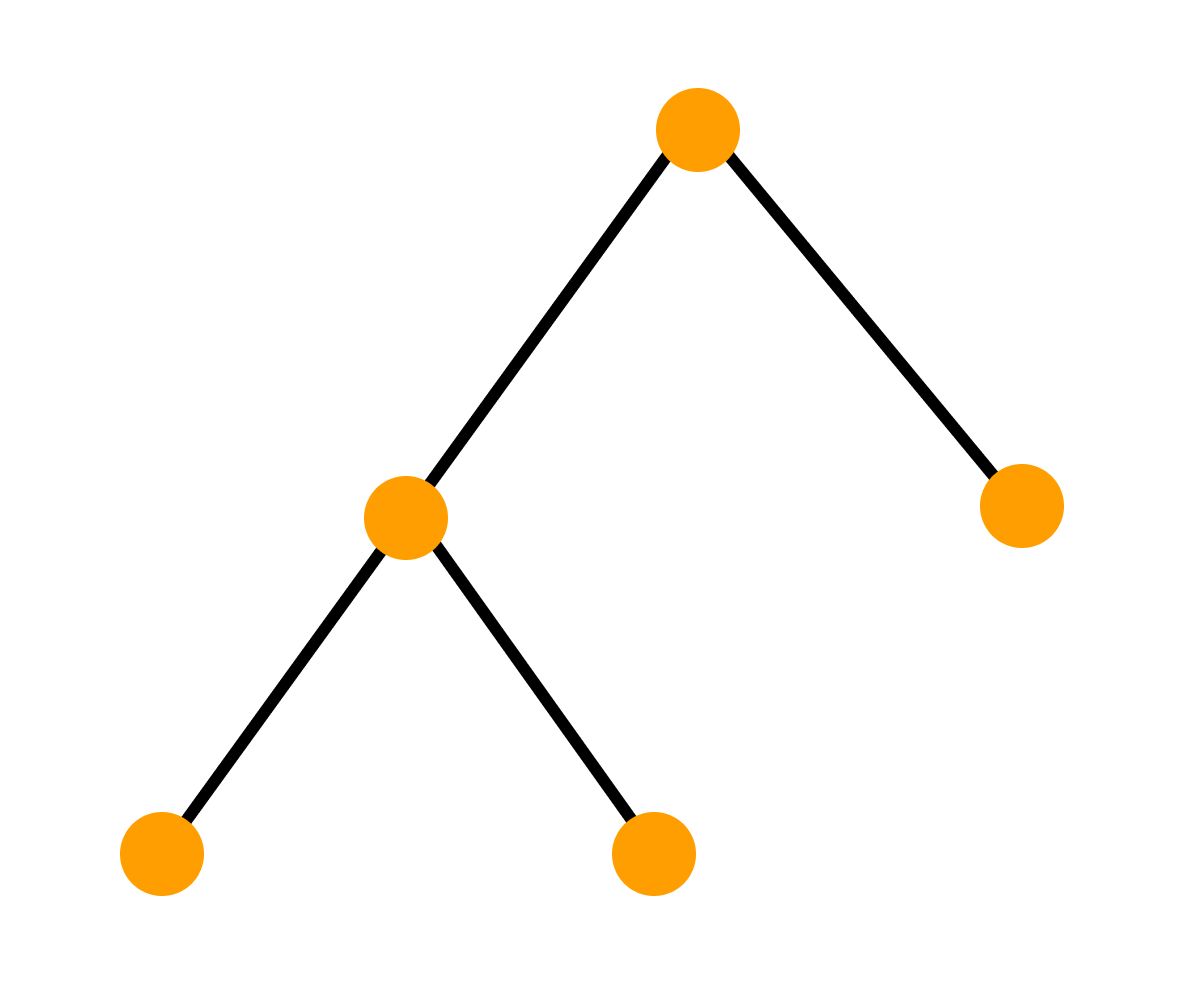

Графы-деревья

Деревом называется связный граф без циклов. Любые две вершины дерева соединены лишь одним маршрутом.

Число q ребер графа находится из соотношения q = n — 1, где n — число вершин дерева.

Приведенное соотношение выражает критическое значение числа рёбер дерева, так как, если мы присоединим к дереву ещё одно ребро — будет создан цикл. А если уберем одно ребро, то граф-дерево разделится на две компоненты. Граф, состоящий из компонент дерева, называется лесом.

Определение дерева

Деревом называется связный граф, который не содержит циклов.

Таким образом, в дереве невозможно вернуться в исходную вершину, перемещаясь по ребрам и не проходя по одному ребру два или более раз.

Циклом называется замкнутый путь, который не проходит дважды через одну и ту же вершину.

Простым путем называется путь, в котором никакое ребро не встречается дважды.

Легко проверить, что дерево — это граф, в котором любые две вершины соединены ровно одним простым путем. Если выкинуть любое ребро из дерева, то граф станет несвязным. Поэтому:

Дерево — минимальный по числу рёбер связный граф.

Висячей вершиной называется вершина, из которой выходит ровно одно ребро.

Определения дерева:

Очень часто в дереве выделяется одна вершина, которая называется корнем дерева. Дерево с выделенным корнем называют корневым или подвешенным деревом. Пример: генеалогическое дерево.

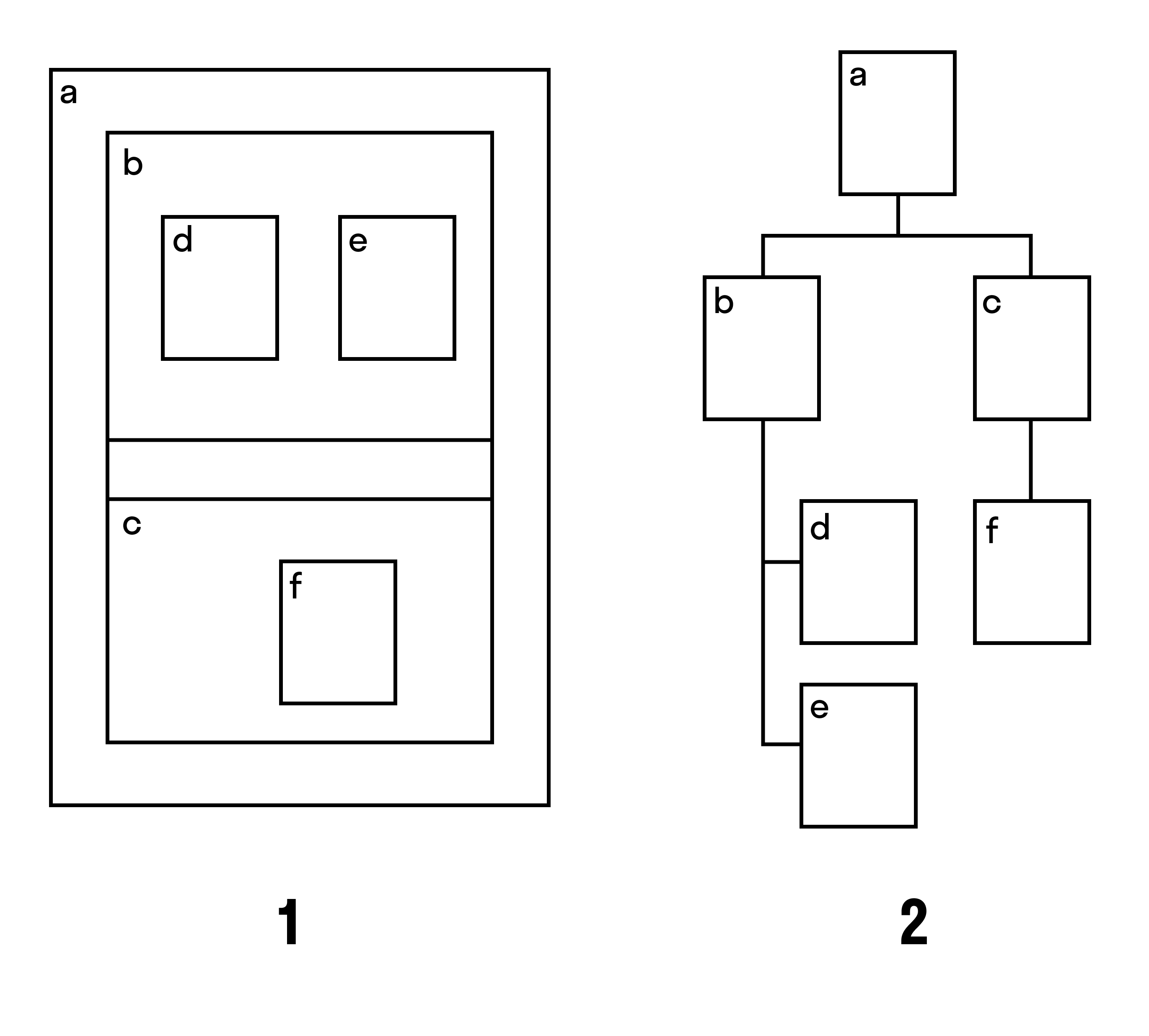

Когда изображают деревья, то часто применяют дополнительные соглашения, эстетические критерии и ограничения.

Например, при соглашении включения (рис. 1) вершины корневого дерева изображают прямоугольниками, а соглашение — опрокидывания (рис. 2) подобно классическому соглашению нисходящего плоского изображения корневого дерева. Вот так могут выглядеть разные изображения одного дерева:

Теоремы дерева и их доказательства

I теорема

В дереве с более чем одной вершиной есть висячая вершина.

Доказательство первой теоремы:

Пойдем из какой-нибудь вершины по ребрам. Так как в дереве нет циклов, то мы не вернемся в вершину, в которой уже побывали. Если у каждой вершины степень больше 1, то найдется ребро, по которому можно уйти из неё после того, как мы пришли в нее.

Но поскольку количество вершин в дереве конечно, когда-нибудь мы остановимся в некоторой вершине. Противоречие. Значит, когда-нибудь мы дойдём в висячую вершину. Если же начать идти из неё, то мы найдём вторую висячую вершину.

II теорема

В дереве число вершин на 1 больше числа ребер.

Доказательство второй теоремы:

Докажем по индукции по количеству вершин в дереве n. Если в дерево одна вершина, то факт верен. Предположим, что для всех n < k мы доказали это факт. Найдём висячую вершину.

Граф, получающийся из исходного выкидыванием висячей вершины вместе с исходящим из нее ребром, очевидно, также является деревом — и в нём меньше на одну вершину и одно ребро. Значит для исходного графа также было верно доказываемое соотношение между количеством вершин и рёбер.

Верна и обратная теорема. Если в связном графе вершин на одну больше, чем ребер, то он является деревом.

Подграф называется остовным деревом, если он является деревом и множество его вершин совпадает с множеством вершин исходного графа.

III теорема

У любого связного графа есть остовное дерево.

Доказательство третьей теоремы:

Чтобы найти остовное дерево графа G, можно найти цикл в графе G и выкинуть одно ребро цикла — потом повторить. И так пока в графе не останется циклов. Полученный граф будет связным, так как мы выкидывали рёбра, не нарушая связность, но в нём не будет циклов. Значит, он будет деревом.

Теория графов и современные прикладные задачи

На основе теории графов создали разные методы решения прикладных задач, в которых в виде графов можно моделировать сложные системы. В этих моделях узлы содержат отдельные компоненты, а ребра отражают связи между компонентами.

Графы и задача о потоках

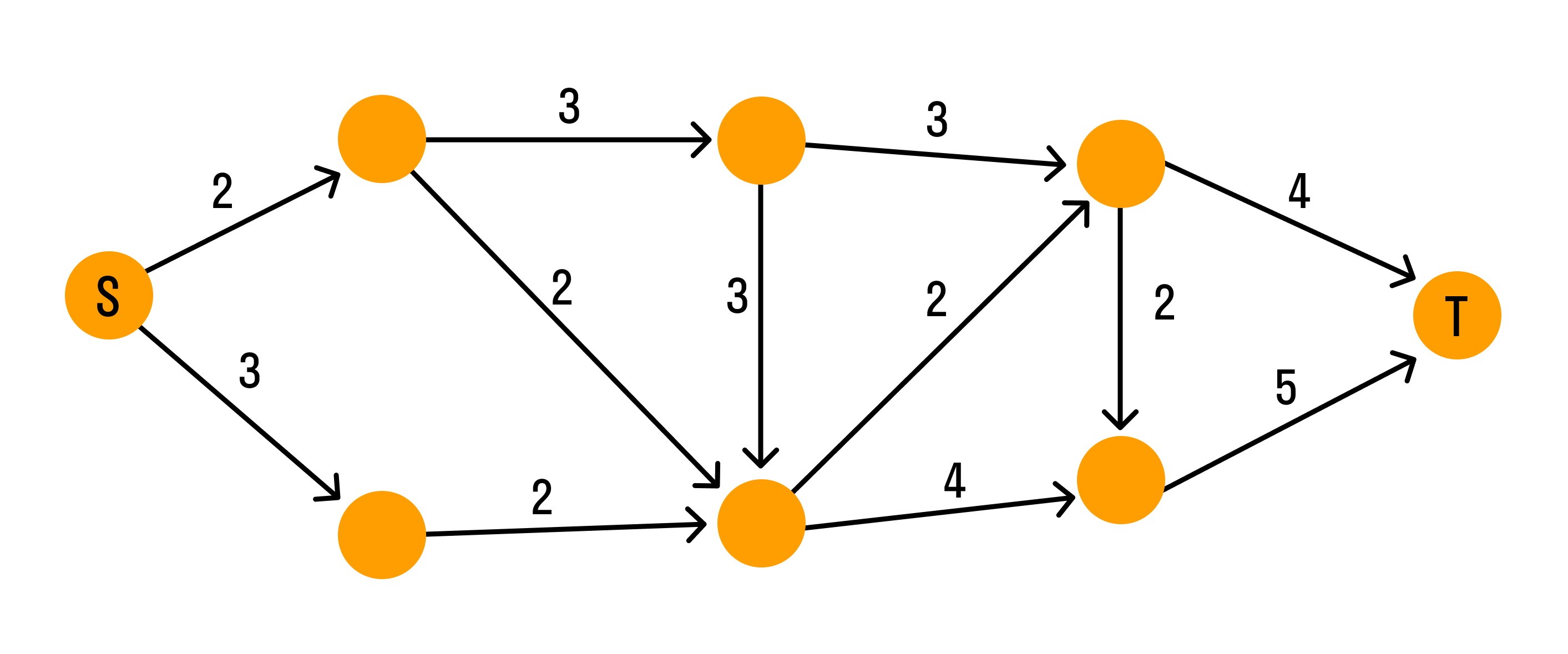

Система водопроводных труб в виде графа выглядит так:

Каждая дуга графа отображает трубу. Числа над дугами (весы) — пропускная способность труб. Узлы — места соединения труб. Вода течёт по трубам только в одном направлении. Узел S — источник воды, узел T — сток.

Задача: максимизировать объём воды, протекающей от источника к стоку.

Для решения задачи о потоках можно использовать метод Форда-Фалкерсона. Идея метода в том, чтобы найти максимальный поток по шагам.

Сначала предполагают, что поток равен нулю. На каждом последующем шаге значение потока увеличивается, для чего ищут дополняющий путь, по которому поступает дополнительный поток. Эти шаги повторяют до тех пор, пока существуют дополнительные пути.

Задачу успешно применяют в различных распределенных системах: система электроснабжения, коммуникационная сеть, система железных дорог.

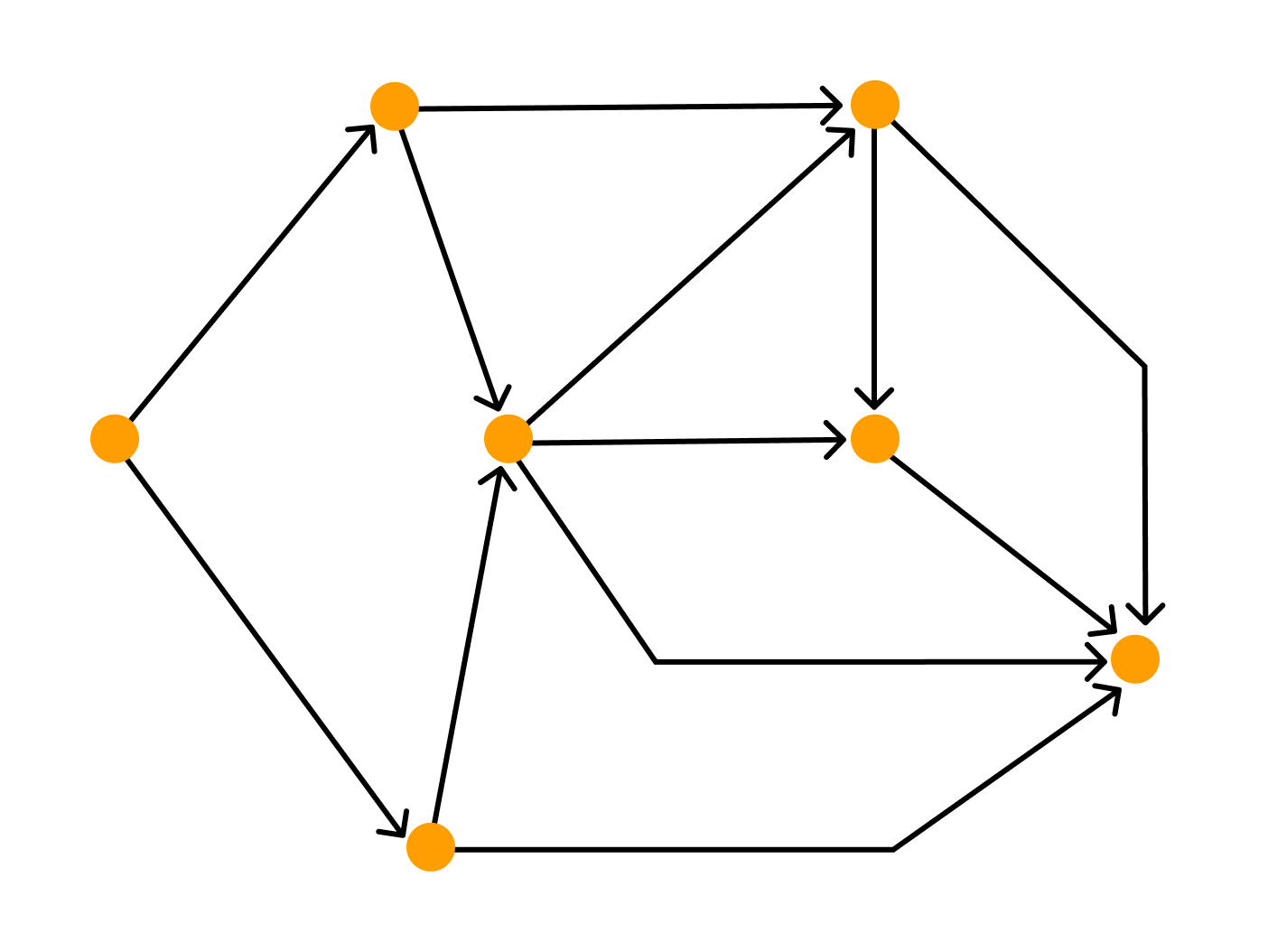

Графы и сетевое планирование

В задачах планирования сложных процессов, где много разных параллельных и последовательных работ, часто используют взвешенные графы. Их еще называют сетью ПЕРТ (PERT).

PERT (Program (Project) Evaluation and Review Technique) — техника оценки и анализа программ (проектов), которую используют при управлении проектами.

Сеть ПЕРТ — взвешенный ациклический ориентированный граф, в котором каждая дуга представляет работу (действие, операцию), а вес дуги — время, которое нужно на ее выполнение.

Если в сети есть дуги (a, b) и (b, c), то работа, представленная дугой (a, b), должна быть завершена до начала выполнения работы, представленной дугой (b, c). Каждая вершина (vi) представляет момент времени, к которому должны быть завершены все работы, задаваемые дугами, оканчивающимися в вершине (vi).

В таком графе:

Путь максимальной длины между этими вершинами графа называется критическим путем. Чтобы выполнить всю работу быстрее, нужно найти задачи на критическом пути и придумать, как их выполнить быстрее. Например, нанять больше людей, перепридумать процесс или ввести новые технологии.

-

Граф

— Пара объектов G = ( X , Г ) ,где Х — конечное

множество ,а Г –конечное подмножество

прямого произведения Х*Х . При этом

Х называется множеством вершин , а Г

— множеством дуг графа G . -

Любое конечное

множество точек (вершин), некоторые из

которых попарно соединены стрелками

, (в теории графов эти стрелки называются

дугами), можно рассматривать как граф. -

Если

в множестве Г все пары упорядочены, то

такой граф называют ориентированным

. -

Дуга—

ребро ориентированного графа. -

Граф

называется вырожденным,

если у него нет рёбер. -

Вершина

Х называется инцидентной

ребру G , если ребро соединяет эту

вершину с какой-либо другой вершиной. -

Подграфом

G(V1,

E1)

графа G(V, E) называется граф с множеством

вершин V1

V

и множеством ребер (дуг) E

E, — такими, что каждое ребро (дуга) из E1

инцидентно

(инцидентна) только вершинам из V1

.

Иначе говоря, подграф содержит некоторые

вершины исходного графа и некоторые

рёбра (только те, оба конца которых

входят в подграф). -

Подграфом,

порождённым множеством вершин U

называется подграф, множество вершин

которого – U,

содержащий те и только те рёбра, оба

конца которых входят в U. -

Подграф называется

остовным

подграфом,

если множество его вершин совпадает с

множеством вершин самого графа. -

Вершины

называются смежными

, если существует ребро , их соединяющее. -

Два

ребра G1

и G2

называются смежными,

если существует вершина, инцидентная

одновременно G1

и G2. -

Каждый

граф можно представить в пространстве

множеством точек, соответствующих

вершинам, которые соединены линиями,

соответствующими ребрам (или дугам — в

последнем случае направление обычно

указывается стрелочками). — такое

представление называется укладкой

графа. -

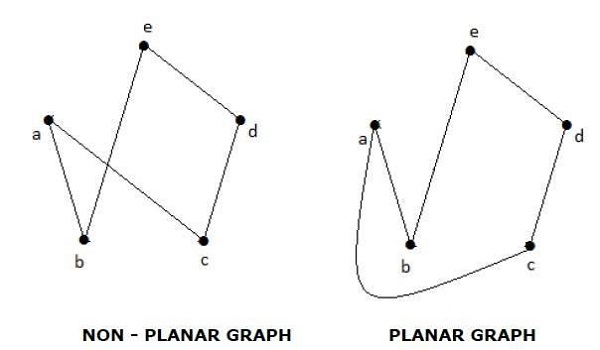

Доказано,

что в 3-мерном пространстве любой граф

можно представить в виде укладки таким

образом, что линии, соответствующие

ребрам (дугам) не будут пересекаться

во внутренних точках. Для 2-мерного

пространства

это,

вообще говоря, неверно. Допускающие

представление в виде укладки в 2-мерном

пространстве графы называют плоскими

(планарным).Другими словами, планарным

называется граф, который может быть

изображен на плоскости так, что его

рёбра не будут пересекаться. -

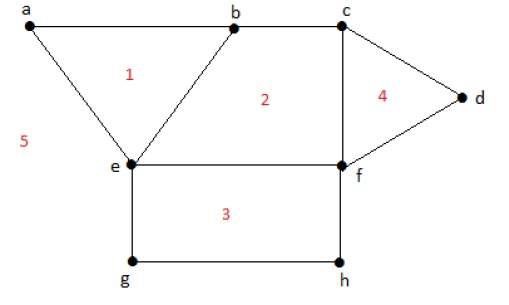

Гранью

графа,

изображенного на некоторой поверхности,

называется часть поверхности, ограниченная

рёбрами графа.

Данное понятие

грани, по — существу, совпадает с понятием

грани многогранника. В качестве

поверхности в этом случае выступает

поверхность многогранника. Если

многогранник выпуклый, его можно

изобразить на плоскости, сохранив все

грани. Это можно наглядно представить

следующим образом: одну из граней

многогранника растягиваем, а сам

многогранник «расплющиваем» так, чтобы

он весь поместился внутри этой грани.

В результате получим плоский граф.

Грань, которую мы растягивали «исчезнет»,

но ей будет соответствовать грань,

состоящая из части плоскости, ограничивающей

граф.

Таким образом,

можно говорить о вершинах, рёбрах и

гранях многогранника, а оперировать

соответствующими понятиями для плоского

графа.

-

Пустым

называется граф без рёбер. Полным

называется граф, в котором каждые две

вершины смежные. -

Конечная

последовательность необязательно

различных рёбер E1,E2,…En

называется маршрутом

длины n, если существует последовательность

V1,

V2,

… Vn

необязательно различных вершин, таких,

что Ei

= (Vi-1,Vi

). -

Если

совпадают, то маршрут замкнутый. -

Маршрут, в котором

все рёбра попарно различны, называется

цепью. -

Замкнутый маршрут,

все рёбра которого различны, называется

циклом. Если все вершины цепи или

цикла различны, то такая цепь или цикл

называются простыми. -

Маршрут, в котором

все вершины попарно различны, называется

простой цепью. -

Цикл, в котором

все вершины, кроме первой и последней,

попарно различны, называется простым

циклом. -

Граф называется

связным, если для любых двух вершин

существует путь, соединяющий эти

вершины. -

Любой максимальный

связный подграф (то есть, не содержащийся

в других связных подграфах) графа G

называется компонентой связности.

Несвязный граф имеет, по крайней мере,

две компоненты связности. -

Граф называется

k — связным (k — реберно — связным),

если удаление не менее k вершин

(ребер) приводит к потере свойства

связности. -

Маршрут, содержащий

все вершины или ребра графа и обладающий

определенными свойствами, называется

обходом графа. -

Длина маршрута

(цепи, простой цепи) равна количеству

ребер а порядке их прохождения. Длина

кратчайшей простой цепи, соединяющей

вершины vi и vj в

графе G, называется расстоянием d

(vi, vj) между vi и vj. -

Степень вершины

— число ребер, которым инцидентна

вершина V, обозначается D(V).

С помощью различных

операций можно строить графы из более

простых, переходить от графа к более

простому, разбивать графы на более

простые и т.д.

Среди

одноместных

операций наиболее употребительны:

удаление и добавление ребра или вершины,

стягивание ребра (отождествление пары

смежных вершин), подразбиение ребра

(т.е. замена ребра

(u,

v)

на пару (u,

w),

(w,

v),

где w

— новая вершина) и др.

Известны двуместные

операции: соединение, сложение, различные

виды умножений графов и др. Такие операции

используются для анализа и синтеза

графов с заданными свойствами.

-

Два

графа G1=(V1;E1),

G2=(V2;E2),называются

изоморфными,

если существует взаимнооднозначное

соответствие между множествами вершин

V1

и V2

и

между множествами рёбер Е1

и Е2,

такое, чтобы сохранялось отношение

инцидентности.

Понятие

изоморфизма для графов имеет наглядное

толкование. Представим рёбра графов

эластичными нитями, связывающими узлы

– вершины. Тогда, изоморфизм можно

представить как перемещение узлов и

растяжение нитей.

Теорема

1.

Пусть

задан граф G=(V;E),где V — множество вершин,

E — множество рёбер, тогда 2[E]=Σ(V), т.е.

удвоенное количество рёбер равно сумме

степеней вершин.

Теорема

2.

(Лемма

о рукопожатиях)

В

конечном графе число вершин нечетной

степени чётно.

Теорема

3.

Граф

связен тогда и только тогда, когда

множество его вершин нельзя разбить на

два непустых подмножества так, чтобы

обе граничные точки каждого ребра

находились в одном и том же множестве.

Расстоянием

между двумя вершинами связного графа

называется длина кратчайшей цепи,

связывающей эти вершины (в количестве

рёбер).

-

Связный

граф без циклов называется деревом.

Деревья особенно

часто возникают на практике при

изображении различных иерархий. Например,

популярные генеалогические деревья.

Пример(генеалогическое

дерево): На

рисунке показано библейское генеалогическое

дерево.

Рис.

7.

Эквивалентные

определения дерева.

-

Связный

граф называется деревом, если он не

имеет циклов. -

Содержит

N-1 ребро и не имеет циклов. -

Связный

и содержит N-1 ребро. -

Связный

и удаление одного любого ребра делает

его несвязным. -

Любая

пара вершин соединяется единственной

цепью. -

Не

имеет циклов и добавление одного ребра

между любыми двумя вершинами приводит

к появлению одного и только одного

цикла.

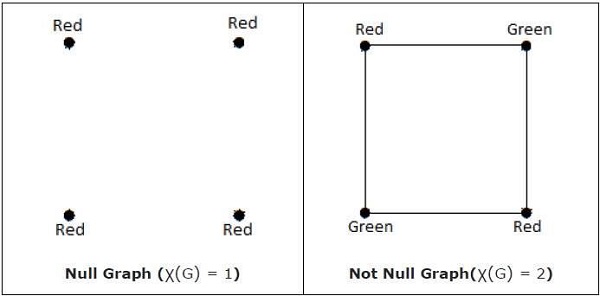

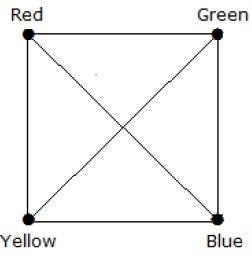

Раскраска

графов

Раскраской

графа G = (V,E) называется отображение D:

V

N . Раскраска называется правильной,

если образы любых двух смежных вершин

различны: D

(U)

≠ D

(V),

если (U,V)

I. Хроматическим

числом графа

называется минимальное количество

красок, необходимое для правильной

раскраски графа.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Структурная теорема графов — фундаментальный результат в теории графов. Результат устанавливает глубокую связь между теорией миноров графов и топологическими вложениями. Теорема была сформулирована в семнадцати статьях из серии из 23 статей Нейла Робертсона[en] и Пола Сеймура. Доказательство теоремы очень длинно и запутано. Каварабайаши и Мохар[1] и Ловаш[2] провели обзор теоремы в доступном для неспециалистов виде, описав теорему и её следствия.

Начала и мотивация теоремы[править | править код]

Минор графа G — это любой граф H, изоморфный графу, который можно получить из подграфа графа G стягиванием некоторых рёбер. Если G не имеет графа H в качестве минора, то мы говорим, что G является H-свободным. Пусть H — фиксированный граф. Интуитивно, если G является большим H-свободным графом, то должна быть какая-то «хорошая причина» для этого. Структурная теорема графов даёт такую «хорошую причину» в форме грубого описания структуры графа G. По существу, любой H-свободный граф G имеет один или два структурных дефекта — либо G «слишком тонок», чтобы содержать H в качестве минора, либо G может быть (почти) топологически вложен в поверхность, которая слишком проста для вложения минора H. Первая причина возникает, когда H планарен, а обе причины возникают в случае непланарности H. Сначала уточним эти понятия.

Древесная ширина[править | править код]

Древесная ширина графа G — это положительное целое число, определяющее «тонкость» графа G. Например, связный граф G имеет древесную ширину единица тогда и только тогда, когда он является деревом, и G имеет древесную ширину два тогда и только тогда, когда он является параллельно-последовательным графом. Интуитивно ясно, что большой граф G имеет маленькую древесную ширину тогда и только тогда, когда G принимает структуру большого дерева, в котором узлы и рёбра заменены маленькими графами. Мы дадим точное определение древесной ширины в подсекции относительно сумм по кликам. Существует теорема, что если H является минором графа G, то древесная ширина H не превосходит древесной ширины G. Таким образом, «хорошей причиной» для G быть H-свободным является не очень большая древесная ширина G. Структурная теорема графов имеет следствием, что эта причина всегда применима в случае планарности H.

Следствие 1. Для любого планарного графа H существует положительное целое k, такое, что любой H-свободный граф имеет древесную ширину, меньшую k.

Значение k в следствии 1, как правило, много больше древесной ширины H (имеется замечательное исключение, когда H = K4, то есть H равен полному графу из четырёх вершин, для которого k=3). Это одна из причин, по которой говорят, что структурная теорема описывает «грубую структуру » H-свободных графов.

Вложение в поверхности[править | править код]

Грубо говоря, поверхность — это множество точек с локальной топологической структурой в виде диска. Поверхности распадаются на два бесконечных семейства — ориентируемые поверхности включают сферу, тор, двойной тор[en] и т.д. Неориентируемые поверхности включают вещественную проективную плоскость, бутылку Клейна и т.д. Граф вкладывается в поверхность, если его можно нарисовать на поверхности в виде множества точек (вершин) и дуг (рёбер) так, что они не пересекают и не касаются друг друга, за исключением случаев, когда вершины и рёбра инцидентны или смежны. Граф планарен, если он вложим в сферу. Если граф G вкладывается в определённую поверхность, то любой минор графа G также вложим в ту же поверхность. Таким образом, «хорошей причиной» для графа G быть H-свободным является возможность вложения графа G в поверхность, в которую H вложить нельзя.

Если H не планарен, структурная теорема графов может рассматриваться как сильное обобщение теоремы Понтрягина — Куратовского. Версия этой теоремы, доказанная Вагнером[3], утверждает, что если граф G является как K5-свободным, так и K3,3-свободным, то G планарен. Эта теорема даёт «хорошую причину» для графа G не содержать K5 или K3,3 в качестве миноров. Конкретнее, G вкладывается в сферу, в то время как ни K5, ни K3,3 в сферу вложить нельзя. Понятия «хорошая причина» недостаточно для структурной теоремы графов. Требуются ещё два понятия — суммы по клике и вихри.

Суммы по клике[править | править код]

Клика в графе G — это любое множество вершин, которые попарно смежны друг другу в G. Для неотрицательного целого k k-кликовая сумма двух графов G и K — это любой граф, полученный выбором в графах G и K клик размером m ≤ k для некоторого неотрицательного m, отождествлением этих двух клик в одну клику (размером m) и удалением некоторого (возможно, нулевого) числа рёбер в этой новой клике.

Если G1, G2, …, Gn — список графов, можно получить новый граф путём объединения графов из списка с помощью сумм по k-кликам. То есть создаём k-кликовую сумму графа G1 и G2, затем создаём k-кликовую сумму графа G3 с предыдущим результирующим графом, и т.д. Граф имеет древесную ширину, не превосходящую k , если он может быть получен как k-кликовая сумма некоторого списка графов, в котором каждый граф имеет максимум k + 1 вершин.

Следствие 1 показывает нам, что k-кликовые суммы малых графов описывают грубую структуру H-свободных графов в случае планарности H. Если H непланарен, мы вынуждены рассматривать также k-кликовые суммы графов, каждый из которых вложим в поверхность. Следующий пример с H = K5 иллюстрирует этот момент. Граф K5 можно вложить в любую поверхность, за исключением сферы. Однако существуют K5-свободные графы, которые далеко не планарны. В частности, 3-кликовая сумма любого списка планарных графов даёт K5-свободный граф. Вагнер[3] определил точную структур K5-свободных графов как часть группы результатов, известных под названием теорема Вагнера:

Теорема 2. Если G свободен от K5, то G можно получить как 3-кликовые суммы списка планарных графов и копий некоторого специфичного непланарного графа с 8 вершинами.

Заметим, что Теорема 2 является точной структурной теоремой, поскольку в точности определяет структуру K5-свободных графов. Такие результаты редки в теории графов. Структурная теорема графов не является точной в том смысле, что для большинства графов H структурное описание H-свободных графов включает некоторые графы, не являющиеся H-свободными.

Вихри (грубое описание)[править | править код]

Имеется искушение предположить, что выполняется аналог теоремы 2 для графов H, отличных от K5. Возможно, это звучало бы так: Для любого непланарного графа H существует положительное число k, такое, что каждый H-свободный граф может быть получен в виде k-кликовой суммы списка графов, каждый из которых либо имеет не более k вершин, либо вкладываем в некоторую поверхность, в которую H вложить нельзя. Данное утверждение слишком просто, чтобы быть правдой. Мы должны позволить каждому вложенному графу Gi «мошенничать» двумя ограниченными способами. Во-первых, мы должны разрешить в ограниченном числе мест на поверхности добавление некоторых новых вершин и рёбер, которым разрешено пересекаться в некоторой ограниченной сложности. Такие места называются вихрями. «Сложность» вихря ограничена параметром, называемым его глубиной, которая тесно связана с путевой шириной графа. Читатель может пропустить чтение точного определения вихря глубины k в следующем разделе. Во-вторых, мы должны позволить добавлять ограниченное число новых вершин для вложенных графов с вихрями.

Вихри (точное определение)[править | править код]

Грань вложенного графа — это открытая 2-ячейка поверхности, не пересекающаяся с графом, но границы которой являются объединением некоторых рёбер вложенного графа. Пусть F — грань вложенного графа G и пусть v0, v1, …, vn−1,vn = v0 — вершины, лежащие на границе F (в порядке цикла). Цикловой интервал для F — это набор вершин вида {va, va+1, …, va+s}, где a и s — целые числа, и где индекс берётся по модулю n. Пусть Λ — это конечный список цикловых интервалов для F. Построим новый граф следующим образом. Для каждого циклового интервала L из Λ добавляем новую вершину vL, соединённую с некоторым числом (возможно, нулевым) вершин из L. Для каждой пары {L, M} интервалов в Λ мы можем добавить ребро, соединяющее vL с vM, если L и M имеют непустое пересечение. Говорят, что образованный граф получен из графа G добавлением вихря глубины, не превосходящей k (к грани F), если никакая вершина на границе F не появляется в более чем k интервалах из Λ.

Утверждение структурной теоремы графов[править | править код]

Структурная теорема графов. Для любого графа H существует положительное целое k, такое, что любой H-свободный граф может быть получен следующим образом:

- Начинаем со списка графов, где каждый граф из списка вложен в поверхность, в которую H вложить нельзя

- к каждому вложенному графу из списка добавляем не более k вихрей и каждый вихрь имеет глубину, не превосходящую k

- к каждому полученному графу добавляем не более k новых вершин (называемых верхушками и добавляем некоторое число рёбер, которые имеют, по крайней мере, один конец в верхушке.

- наконец, соединяем с помощью k-кликовых сумм получившийся список графов.

Заметим, что шаги 1 и 2 дают пустые графы, если граф H планарен, но ограниченное число вершин, добавляемых на шаге 3, делает утверждение совместимым со Следствием 1.

Уточнения[править | править код]

Усиленные версии структурной теоремы графов возможны в зависимости от множества H запрещённых миноров. Например, если один из графов в H планарен, то любой H-свободный граф имеет древесную декомпозицию ограниченной ширины. Эквивалентно он может быть представлен как сумма по клике графов постоянного размера[4]. Если один из графов H может быть нарисован в плоскости с одним пересечением, то H-минорно-свободные графы допускают разложение на кликовую сумму графов с постоянным размером и графов с ограниченным родом (не используя вихри)[5][6]).

Известны также различные усиления, если один из графов H является верхушечным графом[7].

См. также[править | править код]

- Теорема Робертсона – Сеймура

Примечания[править | править код]

- ↑ Kawarabayashi, Mohar, 2007.

- ↑ Lovász, 2006.

- ↑ 1 2 Wagner, 1937.

- ↑ Robertson, Seymour, 1986 V.

- ↑ Robertson, Seymour, 1993.

- ↑ Demaine, Hajiaghayi, Thilikos, 2002.

- ↑ Demaine, Hajiaghayi, Kawarabayashi, 2009.

Литература[править | править код]

- Erik D. Demaine, Mohammad Taghi Hajiaghayi, Ken-ichi Kawarabayashi. Proc. 36th International Colloquium Automata, Languages and Programming (ICALP ’09). — Springer-Verlag, 2009. — Т. 5555. — С. 316–327. — (Lecture Notes in Computer Science). — doi:10.1007/978-3-642-02927-1_27..

- Erik D. Demaine, Mohammad Taghi Hajiaghayi, Dimitrios M. Thilikos. Proc. 5th International Workshop on Approximation Algorithms for Combinatorial Optimization (APPROX 2002). — Springer-Verlag, 2002. — Т. 2462. — С. 67–80. — (Lecture Notes in Computer Science). — doi:10.1007/3-540-45753-4_8..

- Ken-ichi Kawarabayashi, Bojan Mohar. Some recent progress and applications in graph minor theory // Graphs and Combinatorics. — 2007. — Т. 23, вып. 1. — С. 1–46. — doi:10.1007/s00373-006-0684-x..

- Lovász. Graph minor theory // Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. — 2006. — Т. 43, вып. 1. — С. 75–86. — doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-05-01088-8..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. I. Excluding a forest // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 1983 I. — Т. 35, вып. 1. — С. 39–61. — doi:10.1016/0095-8956(83)90079-5..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. II. Algorithmic aspects of tree-width // Journal of Algorithms. — 1986 II. — Т. 7, вып. 3. — С. 309–322. — doi:10.1016/0196-6774(86)90023-4..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. III. Planar tree-width // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 1984 III. — Т. 36, вып. 1. — С. 49–64. — doi:10.1016/0095-8956(84)90013-3..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. IV. Tree-width and well-quasi-ordering // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 1990 IV. — Т. 48, вып. 2. — С. 227–254. — doi:10.1016/0095-8956(90)90120-O..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. V. Excluding a planar graph // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 1986 V. — Т. 41, вып. 1. — С. 92–114. — doi:10.1016/0095-8956(86)90030-4..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. VI. Disjoint paths across a disc // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 1986 VI. — Т. 41, вып. 1. — С. 115–138. — doi:10.1016/0095-8956(86)90031-6..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. VII. Disjoint paths on a surface // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 1988 VII. — Т. 45, вып. 2. — С. 212–254. — doi:10.1016/0095-8956(88)90070-6..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. VIII. A Kuratowski theorem for general surfaces // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 1990 VIII. — Т. 48, вып. 2. — С. 255–288. — doi:10.1016/0095-8956(90)90121-F..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. IX. Disjoint crossed paths // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 1990 IX. — Т. 49, вып. 1. — С. 40–77. — doi:10.1016/0095-8956(90)90063-6..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. X. Obstructions to tree-decomposition // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 1991 X. — Т. 52, вып. 2. — С. 153–190. — doi:10.1016/0095-8956(91)90061-N..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph Structure Theory: Proc. AMS–IMS–SIAM Joint Summer Research Conference on Graph Minors / Neil Robertson, Paul Seymour. — American Mathematical Society, 1993. — Т. 147. — С. 669–675. — (Contemporary Mathematics). — doi:10.1090/conm/147/01206..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. XI. Circuits on a surface // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 1994 XI. — Т. 60, вып. 1. — С. 72–106. — doi:10.1006/jctb.1994.1007..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. XII. Distance on a surface // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 1995 XII. — Т. 64, вып. 2. — С. 240–272. — doi:10.1006/jctb.1995.1034..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. XIII. The disjoint paths problem // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 1995 XIII. — Т. 63, вып. 1. — С. 65–110. — doi:10.1006/jctb.1995.1006..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. XIV. Extending an embedding // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 1995 XIV. — Т. 65, вып. 1. — С. 23–50. — doi:10.1006/jctb.1995.1042..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. XV. Giant steps // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 1996 XV. — Т. 68, вып. 1. — С. 112–148. — doi:10.1006/jctb.1996.0059.

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. XVI. Excluding a non-planar graph // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 2003 XVI. — Т. 89, вып. 1. — С. 43–76. — doi:10.1016/S0095-8956(03)00042-X..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. XVII. Taming a vortex // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 1999 XVII. — Т. 77, вып. 1. — С. 162–210. — doi:10.1006/jctb.1999.1919..

- Neil Robertson, Paul Seymour. Graph minors. XVIII. Tree-decompositions and well-quasi-ordering // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 2003 XVII. — Т. 89, вып. 1. — С. 77–108. — doi:10.1016/S0095-8956(03)00067-4..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. XIX. Well-quasi-ordering on a surface // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 2004 XIX. — Т. 90, вып. 2. — С. 325–385. — doi:10.1016/j.jctb.2003.08.005..

- Neil Robertson, P. D. Seymour. Graph minors. XX. Wagner’s conjecture // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 2004 XX. — Т. 92, вып. 2. — С. 325–357. — doi:10.1016/j.jctb.2004.08.001..

- Neil Robertson, Paul Seymour. Graph minors. XXI. Graphs with unique linkages // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 2009 XXI. — Т. 99, вып. 3. — С. 583–616. — doi:10.1016/j.jctb.2008.08.003..

- Neil Robertson, Paul Seymour. Graph minors. XXII. Irrelevant vertices in linkage problems // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 2012 XXII. — Т. 102, вып. 2. — С. 530–563. — doi:10.1016/j.jctb.2007.12.007..

- Neil Robertson, Paul Seymour. Graph minors XXIII. Nash-Williams’ immersion conjecture // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. — 2010 XXIII. — Т. 100, вып. 2. — С. 181–205. — doi:10.1016/j.jctb.2009.07.003..

- Klaus Wagner. Über eine Erweiterung des Satzes von Kuratowski // Deutsche Mathematik. — 1937. — Т. 2. — С. 280–285..

Здесь собраны теоремы из теории графов.

Содержание

- 1 Лемма о рукопожатиях

- 2 Существование эйлерова пути и цикла

- 3 Теорема (Л. Эйлер, 1736 г.)

- 4 Теорема для орграфов

- 5 Литература

Лемма о рукопожатиях

Сумма степеней всех вершин графа — четное число, равное удвоенному числу ребер:

Следствие. В любом графе число вершин нечетной степени четно

Существование эйлерова пути и цикла

Теорема (Л. Эйлер, 1736 г.)

Связный граф является эйлеровым тогда и только тогда, когда степени всех его вершин четны.

Теорема для орграфов

Связный орграф

Литература

- Оре О. Теория графов. 2-е изд. — М.: Наука, 1980. — 336 с.

- Харари Ф. Теория графов. — М.: Мир, 1973.

- Салий В. Н. Богомолов А. М. Алгебраические основы теории дискретных систем. — М.: Физико-математическая литература, 1997. — ISBN 5-02-015033-9

Graph Theory — Introduction

In the domain of mathematics and computer science, graph theory is the study of graphs that concerns with the relationship among edges and vertices. It is a popular subject having its applications in computer science, information technology, biosciences, mathematics, and linguistics to name a few. Without further ado, let us start with defining a graph.

What is a Graph?

A graph is a pictorial representation of a set of objects where some pairs of objects are connected by links. The interconnected objects are represented by points termed as vertices, and the links that connect the vertices are called edges.

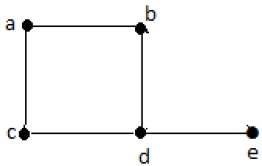

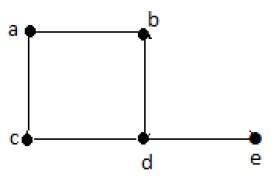

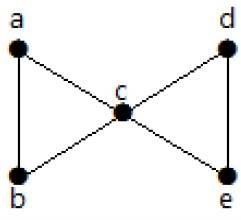

Formally, a graph is a pair of sets (V, E), where V is the set of vertices and E is the set of edges, connecting the pairs of vertices. Take a look at the following graph −

In the above graph,

V = {a, b, c, d, e}

E = {ab, ac, bd, cd, de}

Applications of Graph Theory

Graph theory has its applications in diverse fields of engineering −

Electrical Engineering − The concepts of graph theory is used extensively in designing circuit connections. The types or organization of connections are named as topologies. Some examples for topologies are star, bridge, series, and parallel topologies.

Computer Science − Graph theory is used for the study of algorithms. For example,

- Kruskal’s Algorithm

- Prim’s Algorithm

- Dijkstra’s Algorithm

Computer Network − The relationships among interconnected computers in the network follows the principles of graph theory.

Science − The molecular structure and chemical structure of a substance, the DNA structure of an organism, etc., are represented by graphs.

Linguistics − The parsing tree of a language and grammar of a language uses graphs.

General − Routes between the cities can be represented using graphs. Depicting hierarchical ordered information such as family tree can be used as a special type of graph called tree.

Graph Theory — Fundamentals

A graph is a diagram of points and lines connected to the points. It has at least one line joining a set of two vertices with no vertex connecting itself. The concept of graphs in graph theory stands up on some basic terms such as point, line, vertex, edge, degree of vertices, properties of graphs, etc. Here, in this chapter, we will cover these fundamentals of graph theory.

Point

A point is a particular position in a one-dimensional, two-dimensional, or three-dimensional space. For better understanding, a point can be denoted by an alphabet. It can be represented with a dot.

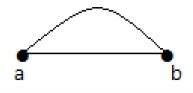

Example

Here, the dot is a point named ‘a’.

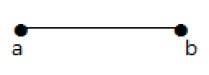

Line

A Line is a connection between two points. It can be represented with a solid line.

Example

Here, ‘a’ and ‘b’ are the points. The link between these two points is called a line.

Vertex

A vertex is a point where multiple lines meet. It is also called a node. Similar to points, a vertex is also denoted by an alphabet.

Example

Here, the vertex is named with an alphabet ‘a’.

Edge

An edge is the mathematical term for a line that connects two vertices. Many edges can be formed from a single vertex. Without a vertex, an edge cannot be formed. There must be a starting vertex and an ending vertex for an edge.

Example

Here, ‘a’ and ‘b’ are the two vertices and the link between them is called an edge.

Graph

A graph ‘G’ is defined as G = (V, E) Where V is a set of all vertices and E is a set of all edges in the graph.

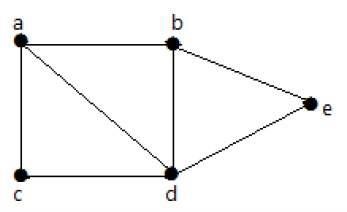

Example 1

In the above example, ab, ac, cd, and bd are the edges of the graph. Similarly, a, b, c, and d are the vertices of the graph.

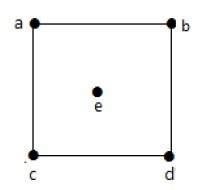

Example 2

In this graph, there are four vertices a, b, c, and d, and four edges ab, ac, ad, and cd.

Loop

In a graph, if an edge is drawn from vertex to itself, it is called a loop.

Example 1

In the above graph, V is a vertex for which it has an edge (V, V) forming a loop.

Example 2

In this graph, there are two loops which are formed at vertex a, and vertex b.

Degree of Vertex

It is the number of vertices adjacent to a vertex V.

Notation − deg(V).

In a simple graph with n number of vertices, the degree of any vertices is −

deg(v) ≤ n – 1 ∀ v ∈ G

A vertex can form an edge with all other vertices except by itself. So the degree of a vertex will be up to the number of vertices in the graph minus 1. This 1 is for the self-vertex as it cannot form a loop by itself. If there is a loop at any of the vertices, then it is not a Simple Graph.

Degree of vertex can be considered under two cases of graphs −

-

Undirected Graph

-

Directed Graph

Degree of Vertex in an Undirected Graph

An undirected graph has no directed edges. Consider the following examples.

Example 1

Take a look at the following graph −

In the above Undirected Graph,

-

deg(a) = 2, as there are 2 edges meeting at vertex ‘a’.

-

deg(b) = 3, as there are 3 edges meeting at vertex ‘b’.

-

deg(c) = 1, as there is 1 edge formed at vertex ‘c’

-

So ‘c’ is a pendent vertex.

-

deg(d) = 2, as there are 2 edges meeting at vertex ‘d’.

-

deg(e) = 0, as there are 0 edges formed at vertex ‘e’.

-

So ‘e’ is an isolated vertex.

Example 2

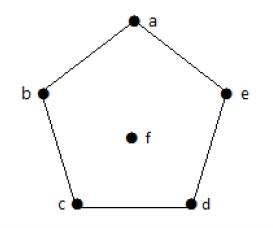

Take a look at the following graph −

In the above graph,

deg(a) = 2, deg(b) = 2, deg(c) = 2, deg(d) = 2, and deg(e) = 0.

The vertex ‘e’ is an isolated vertex. The graph does not have any pendent vertex.

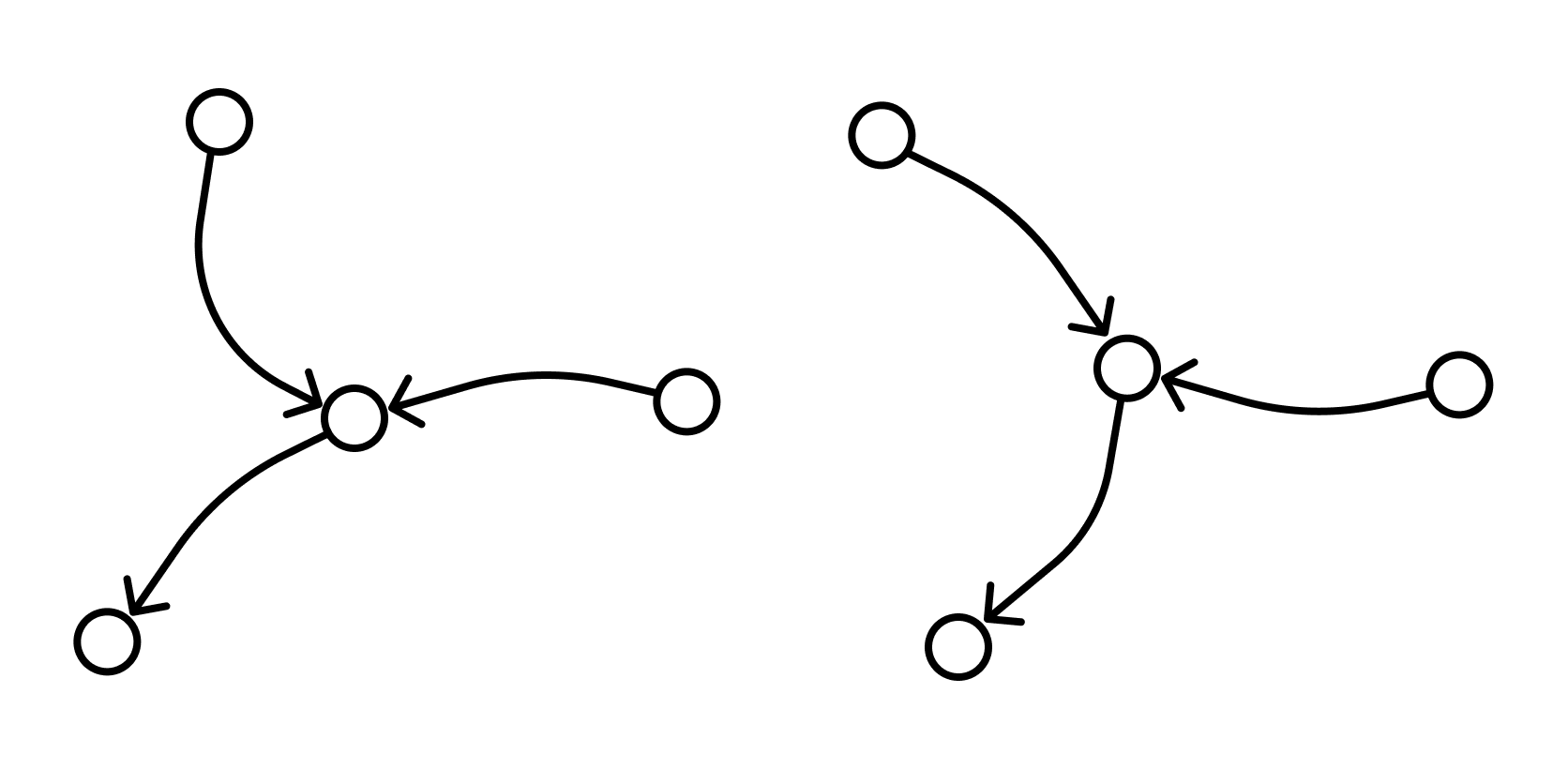

Degree of Vertex in a Directed Graph

In a directed graph, each vertex has an indegree and an outdegree.

Indegree of a Graph

-

Indegree of vertex V is the number of edges which are coming into the vertex V.

-

Notation − deg−(V).

Outdegree of a Graph

-

Outdegree of vertex V is the number of edges which are going out from the vertex V.

-

Notation − deg+(V).

Consider the following examples.

Example 1

Take a look at the following directed graph. Vertex ‘a’ has two edges, ‘ad’ and ‘ab’, which are going outwards. Hence its outdegree is 2. Similarly, there is an edge ‘ga’, coming towards vertex ‘a’. Hence the indegree of ‘a’ is 1.

The indegree and outdegree of other vertices are shown in the following table −

| Vertex | Indegree | Outdegree |

|---|---|---|

| a | 1 | 2 |

| b | 2 | 0 |

| c | 2 | 1 |

| d | 1 | 1 |

| e | 1 | 1 |

| f | 1 | 1 |

| g | 0 | 2 |

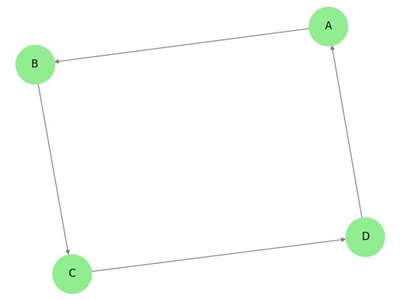

Example 2

Take a look at the following directed graph. Vertex ‘a’ has an edge ‘ae’ going outwards from vertex ‘a’. Hence its outdegree is 1. Similarly, the graph has an edge ‘ba’ coming towards vertex ‘a’. Hence the indegree of ‘a’ is 1.

The indegree and outdegree of other vertices are shown in the following table −

| Vertex | Indegree | Outdegree |

|---|---|---|

| a | 1 | 1 |

| b | 0 | 2 |

| c | 2 | 0 |

| d | 1 | 1 |

| e | 1 | 1 |

Pendent Vertex

By using degree of a vertex, we have a two special types of vertices. A vertex with degree one is called a pendent vertex.

Example

Here, in this example, vertex ‘a’ and vertex ‘b’ have a connected edge ‘ab’. So with respect to the vertex ‘a’, there is only one edge towards vertex ‘b’ and similarly with respect to the vertex ‘b’, there is only one edge towards vertex ‘a’. Finally, vertex ‘a’ and vertex ‘b’ has degree as one which are also called as the pendent vertex.

Isolated Vertex

A vertex with degree zero is called an isolated vertex.

Example

Here, the vertex ‘a’ and vertex ‘b’ has a no connectivity between each other and also to any other vertices. So the degree of both the vertices ‘a’ and ‘b’ are zero. These are also called as isolated vertices.

Adjacency

Here are the norms of adjacency −

-

In a graph, two vertices are said to be adjacent, if there is an edge between the two vertices. Here, the adjacency of vertices is maintained by the single edge that is connecting those two vertices.

-

In a graph, two edges are said to be adjacent, if there is a common vertex between the two edges. Here, the adjacency of edges is maintained by the single vertex that is connecting two edges.

Example 1

In the above graph −

-

‘a’ and ‘b’ are the adjacent vertices, as there is a common edge ‘ab’ between them.

-

‘a’ and ‘d’ are the adjacent vertices, as there is a common edge ‘ad’ between them.

-

ab’ and ‘be’ are the adjacent edges, as there is a common vertex ‘b’ between them.

-

be’ and ‘de’ are the adjacent edges, as there is a common vertex ‘e’ between them.

Example 2

In the above graph −

-

‘a’ and ‘d’ are the adjacent vertices, as there is a common edge ‘ad’ between them.

-

‘c’ and ‘b’ are the adjacent vertices, as there is a common edge ‘cb’ between them.

-

‘ad’ and ‘cd’ are the adjacent edges, as there is a common vertex ‘d’ between them.

-

‘ac’ and ‘cd’ are the adjacent edges, as there is a common vertex ‘c’ between them.

Parallel Edges

In a graph, if a pair of vertices is connected by more than one edge, then those edges are called parallel edges.

In the above graph, ‘a’ and ‘b’ are the two vertices which are connected by two edges ‘ab’ and ‘ab’ between them. So it is called as a parallel edge.

Multi Graph

A graph having parallel edges is known as a Multigraph.

Example 1

In the above graph, there are five edges ‘ab’, ‘ac’, ‘cd’, ‘cd’, and ‘bd’. Since ‘c’ and ‘d’ have two parallel edges between them, it a Multigraph.

Example 2

In the above graph, the vertices ‘b’ and ‘c’ have two edges. The vertices ‘e’ and ‘d’ also have two edges between them. Hence it is a Multigraph.

Degree Sequence of a Graph

If the degrees of all vertices in a graph are arranged in descending or ascending order, then the sequence obtained is known as the degree sequence of the graph.

Example 1

| Vertex | A | b | c | d | e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connecting to | b,c | a,d | a,d | c,b,e | d |

| Degree | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

In the above graph, for the vertices {d, a, b, c, e}, the degree sequence is {3, 2, 2, 2, 1}.

Example 2

| Vertex | A | b | c | d | e | f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connecting to | b,e | a,c | b,d | c,e | a,d | — |

| Degree | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

In the above graph, for the vertices {a, b, c, d, e, f}, the degree sequence is {2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 0}.

Graph Theory — Basic Properties

Graphs come with various properties which are used for characterization of graphs depending on their structures. These properties are defined in specific terms pertaining to the domain of graph theory. In this chapter, we will discuss a few basic properties that are common in all graphs.

Distance between Two Vertices

It is number of edges in a shortest path between Vertex U and Vertex V. If there are multiple paths connecting two vertices, then the shortest path is considered as the distance between the two vertices.

Notation − d(U,V)

There can be any number of paths present from one vertex to other. Among those, you need to choose only the shortest one.

Example

Take a look at the following graph −

Here, the distance from vertex ‘d’ to vertex ‘e’ or simply ‘de’ is 1 as there is one edge between them. There are many paths from vertex ‘d’ to vertex ‘e’ −

- da, ab, be

- df, fg, ge

- de (It is considered for distance between the vertices)

- df, fc, ca, ab, be

- da, ac, cf, fg, ge

Eccentricity of a Vertex

The maximum distance between a vertex to all other vertices is considered as the eccentricity of vertex.

Notation − e(V)

The distance from a particular vertex to all other vertices in the graph is taken and among those distances, the eccentricity is the highest of distances.

Example

In the above graph, the eccentricity of ‘a’ is 3.

The distance from ‘a’ to ‘b’ is 1 (‘ab’),

from ‘a’ to ‘c’ is 1 (‘ac’),

from ‘a’ to ‘d’ is 1 (‘ad’),

from ‘a’ to ‘e’ is 2 (‘ab’-‘be’) or (‘ad’-‘de’),

from ‘a’ to ‘f’ is 2 (‘ac’-‘cf’) or (‘ad’-‘df’),

from ‘a’ to ‘g’ is 3 (‘ac’-‘cf’-‘fg’) or (‘ad’-‘df’-‘fg’).

So the eccentricity is 3, which is a maximum from vertex ‘a’ from the distance between ‘ag’ which is maximum.

In other words,

e(b) = 3

e(c) = 3

e(d) = 2

e(e) = 3

e(f) = 3

e(g) = 3

Radius of a Connected Graph

The minimum eccentricity from all the vertices is considered as the radius of the Graph G. The minimum among all the maximum distances between a vertex to all other vertices is considered as the radius of the Graph G.

Notation − r(G)

From all the eccentricities of the vertices in a graph, the radius of the connected graph is the minimum of all those eccentricities.

Example

In the above graph r(G) = 2, which is the minimum eccentricity for ‘d’.

Diameter of a Graph

The maximum eccentricity from all the vertices is considered as the diameter of the Graph G. The maximum among all the distances between a vertex to all other vertices is considered as the diameter of the Graph G.

Notation − d(G) − From all the eccentricities of the vertices in a graph, the diameter of the connected graph is the maximum of all those eccentricities.

Example

In the above graph, d(G) = 3; which is the maximum eccentricity.

Central Point

If the eccentricity of a graph is equal to its radius, then it is known as the central point of the graph. If

e(V) = r(V),

then ‘V’ is the central point of the Graph ’G’.

Example

In the example graph, ‘d’ is the central point of the graph.

e(d) = r(d) = 2

Centre

The set of all central points of ‘G’ is called the centre of the Graph.

Example

In the example graph, {‘d’} is the centre of the Graph.

Circumference

The number of edges in the longest cycle of ‘G’ is called as the circumference of ‘G’.

Example

In the example graph, the circumference is 6, which we derived from the longest cycle a-c-f-g-e-b-a or a-c-f-d-e-b-a.

Girth

The number of edges in the shortest cycle of ‘G’ is called its Girth.

Notation: g(G).

Example − In the example graph, the Girth of the graph is 4, which we derived from the shortest cycle a-c-f-d-a or d-f-g-e-d or a-b-e-d-a.

Sum of Degrees of Vertices Theorem

If G = (V, E) be a non-directed graph with vertices V = {V1, V2,…Vn} then

n Σ i=1 deg(Vi) = 2|E|

Corollary 1

If G = (V, E) be a directed graph with vertices V = {V1, V2,…Vn}, then

n Σ i=1 deg+(Vi) = |E| = n Σ i=1 deg−(Vi)

Corollary 2

In any non-directed graph, the number of vertices with Odd degree is Even.

Corollary 3

In a non-directed graph, if the degree of each vertex is k, then

k|V| = 2|E|

Corollary 4

In a non-directed graph, if the degree of each vertex is at least k, then

k|V| ≤ 2|E|

| Corollary 5

In a non-directed graph, if the degree of each vertex is at most k, then

k|V| ≥ 2|E|

Graph Theory — Types of Graphs

There are various types of graphs depending upon the number of vertices, number of edges, interconnectivity, and their overall structure. We will discuss only a certain few important types of graphs in this chapter.

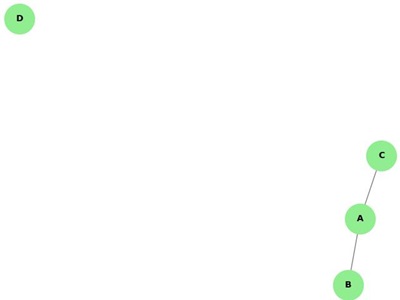

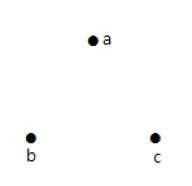

Null Graph

A graph having no edges is called a Null Graph.

Example

In the above graph, there are three vertices named ‘a’, ‘b’, and ‘c’, but there are no edges among them. Hence it is a Null Graph.

Trivial Graph

A graph with only one vertex is called a Trivial Graph.

Example

In the above shown graph, there is only one vertex ‘a’ with no other edges. Hence it is a Trivial graph.

Non-Directed Graph

A non-directed graph contains edges but the edges are not directed ones.

Example

In this graph, ‘a’, ‘b’, ‘c’, ‘d’, ‘e’, ‘f’, ‘g’ are the vertices, and ‘ab’, ‘bc’, ‘cd’, ‘da’, ‘ag’, ‘gf’, ‘ef’ are the edges of the graph. Since it is a non-directed graph, the edges ‘ab’ and ‘ba’ are same. Similarly other edges also considered in the same way.

Directed Graph

In a directed graph, each edge has a direction.

Example

In the above graph, we have seven vertices ‘a’, ‘b’, ‘c’, ‘d’, ‘e’, ‘f’, and ‘g’, and eight edges ‘ab’, ‘cb’, ‘dc’, ‘ad’, ‘ec’, ‘fe’, ‘gf’, and ‘ga’. As it is a directed graph, each edge bears an arrow mark that shows its direction. Note that in a directed graph, ‘ab’ is different from ‘ba’.

Simple Graph

A graph with no loops and no parallel edges is called a simple graph.

-

The maximum number of edges possible in a single graph with ‘n’ vertices is nC2 where nC2 = n(n – 1)/2.

-

The number of simple graphs possible with ‘n’ vertices = 2nc2 = 2n(n-1)/2.

Example

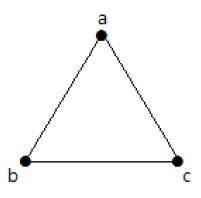

In the following graph, there are 3 vertices with 3 edges which is maximum excluding the parallel edges and loops. This can be proved by using the above formulae.

The maximum number of edges with n=3 vertices −

nC2 = n(n–1)/2

= 3(3–1)/2

= 6/2

= 3 edges

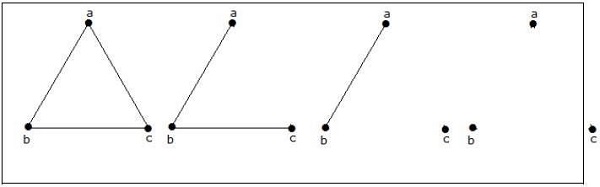

The maximum number of simple graphs with n=3 vertices −

2nC2 = 2n(n-1)/2

= 23(3-1)/2

= 23

8

These 8 graphs are as shown below −

Connected Graph

A graph G is said to be connected if there exists a path between every pair of vertices. There should be at least one edge for every vertex in the graph. So that we can say that it is connected to some other vertex at the other side of the edge.

Example

In the following graph, each vertex has its own edge connected to other edge. Hence it is a connected graph.

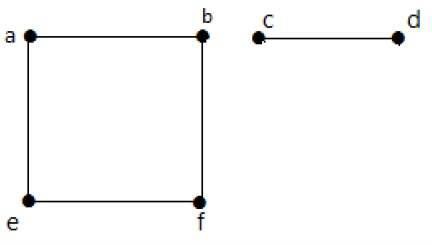

Disconnected Graph

A graph G is disconnected, if it does not contain at least two connected vertices.

Example 1

The following graph is an example of a Disconnected Graph, where there are two components, one with ‘a’, ‘b’, ‘c’, ‘d’ vertices and another with ‘e’, ’f’, ‘g’, ‘h’ vertices.

The two components are independent and not connected to each other. Hence it is called disconnected graph.

Example 2

In this example, there are two independent components, a-b-f-e and c-d, which are not connected to each other. Hence this is a disconnected graph.

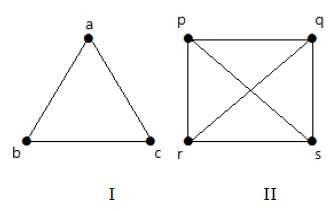

Regular Graph

A graph G is said to be regular, if all its vertices have the same degree. In a graph, if the degree of each vertex is ‘k’, then the graph is called a ‘k-regular graph’.

Example

In the following graphs, all the vertices have the same degree. So these graphs are called regular graphs.

In both the graphs, all the vertices have degree 2. They are called 2-Regular Graphs.

Complete Graph

A simple graph with ‘n’ mutual vertices is called a complete graph and it is denoted by ‘Kn’. In the graph, a vertex should have edges with all other vertices, then it called a complete graph.

In other words, if a vertex is connected to all other vertices in a graph, then it is called a complete graph.

Example

In the following graphs, each vertex in the graph is connected with all the remaining vertices in the graph except by itself.

In graph I,

| a | b | c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | Not Connected | Connected | Connected |

| b | Connected | Not Connected | Connected |

| c | Connected | Connected | Not Connected |

In graph II,

| p | q | r | s | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | Not Connected | Connected | Connected | Connected |

| q | Connected | Not Connected | Connected | Connected |

| r | Connected | Connected | Not Connected | Connected |

| s | Connected | Connected | Connected | Not Connected |

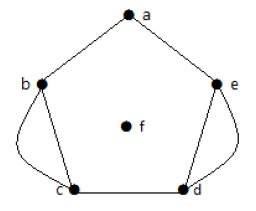

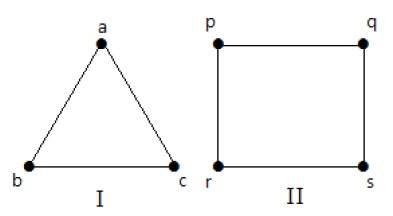

Cycle Graph

A simple graph with ‘n’ vertices (n >= 3) and ‘n’ edges is called a cycle graph if all its edges form a cycle of length ‘n’.

If the degree of each vertex in the graph is two, then it is called a Cycle Graph.

Notation − Cn

Example

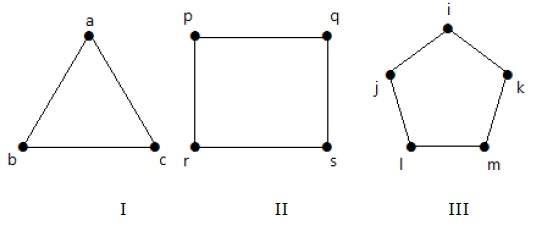

Take a look at the following graphs −

-

Graph I has 3 vertices with 3 edges which is forming a cycle ‘ab-bc-ca’.

-

Graph II has 4 vertices with 4 edges which is forming a cycle ‘pq-qs-sr-rp’.

-

Graph III has 5 vertices with 5 edges which is forming a cycle ‘ik-km-ml-lj-ji’.

Hence all the given graphs are cycle graphs.

Wheel Graph

A wheel graph is obtained from a cycle graph Cn-1 by adding a new vertex. That new vertex is called a Hub which is connected to all the vertices of Cn.

Notation − Wn

No. of edges in Wn = No. of edges from hub to all other vertices +

No. of edges from all other nodes in cycle graph without a hub.

= (n–1) + (n–1)

= 2(n–1)

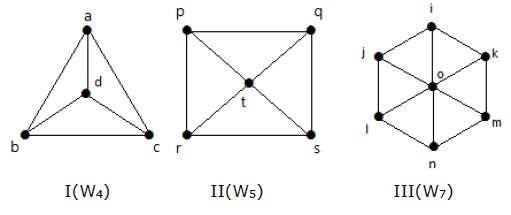

Example

Take a look at the following graphs. They are all wheel graphs.

In graph I, it is obtained from C3 by adding an vertex at the middle named as ‘d’. It is denoted as W4.

Number of edges in W4 = 2(n-1) = 2(3) = 6

In graph II, it is obtained from C4 by adding a vertex at the middle named as ‘t’. It is denoted as W5.

Number of edges in W5 = 2(n-1) = 2(4) = 8

In graph III, it is obtained from C6 by adding a vertex at the middle named as ‘o’. It is denoted as W7.

Number of edges in W4 = 2(n-1) = 2(6) = 12

Cyclic Graph

A graph with at least one cycle is called a cyclic graph.

Example

In the above example graph, we have two cycles a-b-c-d-a and c-f-g-e-c. Hence it is called a cyclic graph.

Acyclic Graph

A graph with no cycles is called an acyclic graph.

Example

In the above example graph, we do not have any cycles. Hence it is a non-cyclic graph.

Bipartite Graph

A simple graph G = (V, E) with vertex partition V = {V1, V2} is called a bipartite graph if every edge of E joins a vertex in V1 to a vertex in V2.

In general, a Bipertite graph has two sets of vertices, let us say, V1 and V2, and if an edge is drawn, it should connect any vertex in set V1 to any vertex in set V2.

Example

In this graph, you can observe two sets of vertices − V1 and V2. Here, two edges named ‘ae’ and ‘bd’ are connecting the vertices of two sets V1 and V2.

Complete Bipartite Graph

A bipartite graph ‘G’, G = (V, E) with partition V = {V1, V2} is said to be a complete bipartite graph if every vertex in V1 is connected to every vertex of V2.

In general, a complete bipartite graph connects each vertex from set V1 to each vertex from set V2.

Example

The following graph is a complete bipartite graph because it has edges connecting each vertex from set V1 to each vertex from set V2.

If |V1| = m and |V2| = n, then the complete bipartite graph is denoted by Km, n.

- Km,n has (m+n) vertices and (mn) edges.

- Km,n is a regular graph if m=n.

In general, a complete bipartite graph is not a complete graph.

Km,n is a complete graph if m=n=1.

The maximum number of edges in a bipartite graph with n vertices is −

[n2/4]

If n=10, k5, 5= [n2/4] = [102/4] = 25.

Similarly, K6, 4=24

K7, 3=21

K8, 2=16

K9, 1=9

If n=9, k5, 4 = [n2/4] = [92/4] = 20

Similarly, K6, 3=18

K7, 2=14

K8, 1=8

‘G’ is a bipartite graph if ‘G’ has no cycles of odd length. A special case of bipartite graph is a star graph.

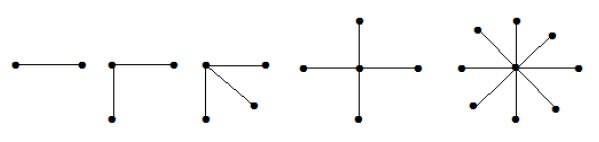

Star Graph

A complete bipartite graph of the form K1, n-1 is a star graph with n-vertices. A star graph is a complete bipartite graph if a single vertex belongs to one set and all the remaining vertices belong to the other set.

Example

In the above graphs, out of ‘n’ vertices, all the ‘n–1’ vertices are connected to a single vertex. Hence it is in the form of K1, n-1 which are star graphs.

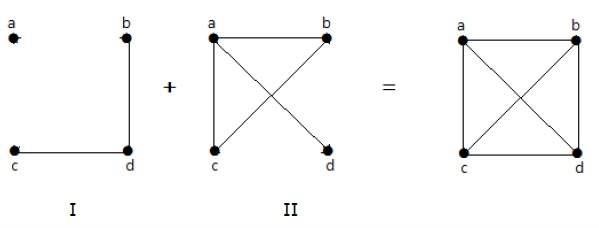

Complement of a Graph

Let ‘G−’ be a simple graph with some vertices as that of ‘G’ and an edge {U, V} is present in ‘G−’, if the edge is not present in G. It means, two vertices are adjacent in ‘G−’ if the two vertices are not adjacent in G.

If the edges that exist in graph I are absent in another graph II, and if both graph I and graph II are combined together to form a complete graph, then graph I and graph II are called complements of each other.

Example

In the following example, graph-I has two edges ‘cd’ and ‘bd’. Its complement graph-II has four edges.

Note that the edges in graph-I are not present in graph-II and vice versa. Hence, the combination of both the graphs gives a complete graph of ‘n’ vertices.

Note − A combination of two complementary graphs gives a complete graph.

If ‘G’ is any simple graph, then

|E(G)| + |E(‘G-‘)| = |E(Kn)|, where n = number of vertices in the graph.

Example

Let ‘G’ be a simple graph with nine vertices and twelve edges, find the number of edges in ‘G-‘.

You have, |E(G)| + |E(‘G-‘)| = |E(Kn)|

12 + |E(‘G-‘)| =

9(9-1) / 2 = 9C2

12 + |E(‘G-‘)| = 36

|E(‘G-‘)| = 24

‘G’ is a simple graph with 40 edges and its complement ‘G−’ has 38 edges. Find the number of vertices in the graph G or ‘G−’.

Let the number of vertices in the graph be ‘n’.

We have, |E(G)| + |E(‘G-‘)| = |E(Kn)|

40 + 38 = n(n-1)/2

156 = n(n-1)

13(12) = n(n-1)

n = 13

Graph Theory — Trees

Trees are graphs that do not contain even a single cycle. They represent hierarchical structure in a graphical form. Trees belong to the simplest class of graphs. Despite their simplicity, they have a rich structure.

Trees provide a range of useful applications as simple as a family tree to as complex as trees in data structures of computer science.

Tree

A connected acyclic graph is called a tree. In other words, a connected graph with no cycles is called a tree.

The edges of a tree are known as branches. Elements of trees are called their nodes. The nodes without child nodes are called leaf nodes.

A tree with ‘n’ vertices has ‘n-1’ edges. If it has one more edge extra than ‘n-1’, then the extra edge should obviously has to pair up with two vertices which leads to form a cycle. Then, it becomes a cyclic graph which is a violation for the tree graph.

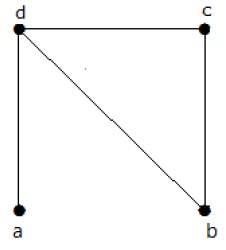

Example 1

The graph shown here is a tree because it has no cycles and it is connected. It has four vertices and three edges, i.e., for ‘n’ vertices ‘n-1’ edges as mentioned in the definition.

Note − Every tree has at least two vertices of degree one.

Example 2

In the above example, the vertices ‘a’ and ‘d’ has degree one. And the other two vertices ‘b’ and ‘c’ has degree two. This is possible because for not forming a cycle, there should be at least two single edges anywhere in the graph. It is nothing but two edges with a degree of one.

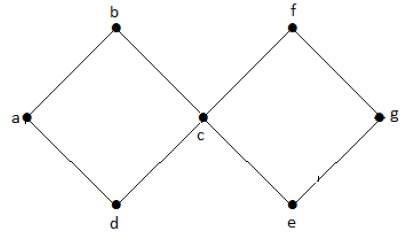

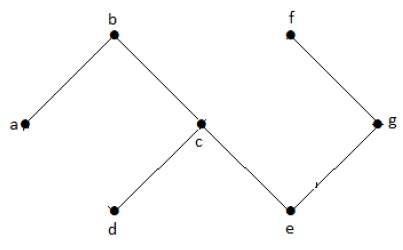

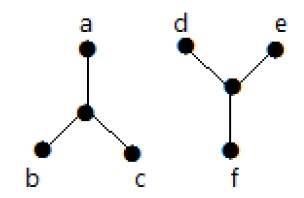

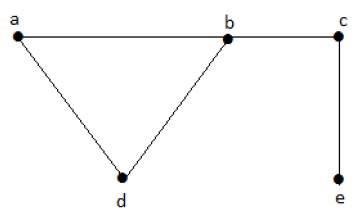

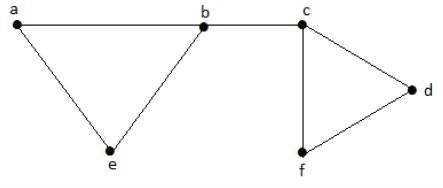

Forest

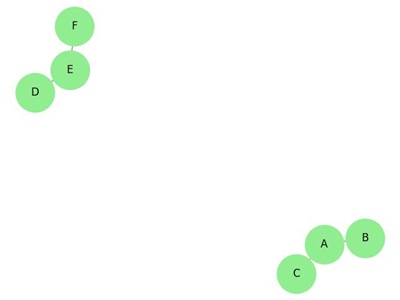

A disconnected acyclic graph is called a forest. In other words, a disjoint collection of trees is called a forest.

Example

The following graph looks like two sub-graphs; but it is a single disconnected graph. There are no cycles in this graph. Hence, clearly it is a forest.

Spanning Trees

Let G be a connected graph, then the sub-graph H of G is called a spanning tree of G if −

- H is a tree

- H contains all vertices of G.

A spanning tree T of an undirected graph G is a subgraph that includes all of the vertices of G.

Example

In the above example, G is a connected graph and H is a sub-graph of G.

Clearly, the graph H has no cycles, it is a tree with six edges which is one less than the total number of vertices. Hence H is the Spanning tree of G.

Circuit Rank

Let ‘G’ be a connected graph with ‘n’ vertices and ‘m’ edges. A spanning tree ‘T’ of G contains (n-1) edges.

Therefore, the number of edges you need to delete from ‘G’ in order to get a spanning tree = m-(n-1), which is called the circuit rank of G.

This formula is true, because in a spanning tree you need to have ‘n-1’ edges. Out of ‘m’ edges, you need to keep ‘n–1’ edges in the graph.

Hence, deleting ‘n–1’ edges from ‘m’ gives the edges to be removed from the graph in order to get a spanning tree, which should not form a cycle.

Example

Take a look at the following graph −

For the graph given in the above example, you have m=7 edges and n=5 vertices.

Then the circuit rank is −

G = m – (n – 1)

= 7 – (5 – 1)

= 3

Example

Let ‘G’ be a connected graph with six vertices and the degree of each vertex is three. Find the circuit rank of ‘G’.

By the sum of degree of vertices theorem,

n Σ i=1 deg(Vi) = 2|E|

6 × 3 = 2|E|

|E| = 9

Circuit rank = |E| – (|V| – 1)

= 9 – (6 – 1) = 4

Kirchoff’s Theorem

Kirchoff’s theorem is useful in finding the number of spanning trees that can be formed from a connected graph.

Example

The matrix ‘A’ be filled as, if there is an edge between two vertices, then it should be given as ‘1’, else ‘0’.

$$A=begin{vmatrix}0 & a & b & c & d\a & 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 \b & 1 & 0 & 0 & 1\c & 1 & 0 & 0 & 1\d & 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 end{vmatrix} = begin{vmatrix} 0 & 1 & 1 & 1\1 & 0 & 0 & 1\1 & 0 & 0 & 1\1 & 1 & 1 & 0end{vmatrix}$$

By using kirchoff’s theorem, it should be changed as replacing the principle diagonal values with the degree of vertices and all other elements with -1.A

$$=begin{vmatrix} 3 & -1 & -1 & -1\-1 & 2 & 0 & -1\-1 & 0 & 2 & -1\-1 & -1 & -1 & 3 end{vmatrix}=M$$

$$M=begin{vmatrix}3 & -1 & -1 & -1\-1 & 2 & 0 & -1\-1 & 0 & 2 & -1\-1 & -1 & -1 & 3 end{vmatrix} =8$$

$$Co::factor::of::m1::= begin{vmatrix} 2 & 0 & -1\0 & 2 & -1\-1 & -1 & 3end{vmatrix}$$

Thus, the number of spanning trees = 8.

Graph Theory — Connectivity

Whether it is possible to traverse a graph from one vertex to another is determined by how a graph is connected. Connectivity is a basic concept in Graph Theory. Connectivity defines whether a graph is connected or disconnected. It has subtopics based on edge and vertex, known as edge connectivity and vertex connectivity. Let us discuss them in detail.

Connectivity

A graph is said to be connected if there is a path between every pair of vertex. From every vertex to any other vertex, there should be some path to traverse. That is called the connectivity of a graph. A graph with multiple disconnected vertices and edges is said to be disconnected.

Example 1

In the following graph, it is possible to travel from one vertex to any other vertex. For example, one can traverse from vertex ‘a’ to vertex ‘e’ using the path ‘a-b-e’.

Example 2

In the following example, traversing from vertex ‘a’ to vertex ‘f’ is not possible because there is no path between them directly or indirectly. Hence it is a disconnected graph.

Cut Vertex

Let ‘G’ be a connected graph. A vertex V ∈ G is called a cut vertex of ‘G’, if ‘G-V’ (Delete ‘V’ from ‘G’) results in a disconnected graph. Removing a cut vertex from a graph breaks it in to two or more graphs.

Note − Removing a cut vertex may render a graph disconnected.

A connected graph ‘G’ may have at most (n–2) cut vertices.

Example

In the following graph, vertices ‘e’ and ‘c’ are the cut vertices.

By removing ‘e’ or ‘c’, the graph will become a disconnected graph.

Without ‘g’, there is no path between vertex ‘c’ and vertex ‘h’ and many other. Hence it is a disconnected graph with cut vertex as ‘e’. Similarly, ‘c’ is also a cut vertex for the above graph.

Cut Edge (Bridge)

Let ‘G’ be a connected graph. An edge ‘e’ ∈ G is called a cut edge if ‘G-e’ results in a disconnected graph.

If removing an edge in a graph results in to two or more graphs, then that edge is called a Cut Edge.

Example

In the following graph, the cut edge is [(c, e)].

By removing the edge (c, e) from the graph, it becomes a disconnected graph.

In the above graph, removing the edge (c, e) breaks the graph into two which is nothing but a disconnected graph. Hence, the edge (c, e) is a cut edge of the graph.

Note − Let ‘G’ be a connected graph with ‘n’ vertices, then

-

a cut edge e ∈ G if and only if the edge ‘e’ is not a part of any cycle in G.

-

the maximum number of cut edges possible is ‘n-1’.

-

whenever cut edges exist, cut vertices also exist because at least one vertex of a cut edge is a cut vertex.

-

if a cut vertex exists, then a cut edge may or may not exist.

Cut Set of a Graph

Let ‘G’= (V, E) be a connected graph. A subset E’ of E is called a cut set of G if deletion of all the edges of E’ from G makes G disconnect.

If deleting a certain number of edges from a graph makes it disconnected, then those deleted edges are called the cut set of the graph.

Example

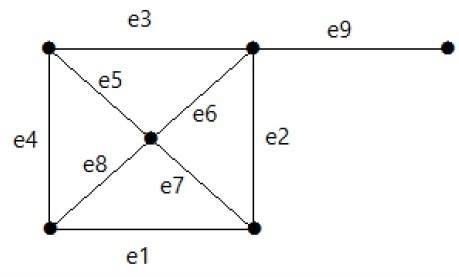

Take a look at the following graph. Its cut set is E1 = {e1, e3, e5, e8}.

After removing the cut set E1 from the graph, it would appear as follows −

Similarly, there are other cut sets that can disconnect the graph −

-

E3 = {e9} – Smallest cut set of the graph.

-

E4 = {e3, e4, e5}

Edge Connectivity

Let ‘G’ be a connected graph. The minimum number of edges whose removal makes ‘G’ disconnected is called edge connectivity of G.

Notation − λ(G)

In other words, the number of edges in a smallest cut set of G is called the edge connectivity of G.