Академическая честность Академическая честность означает, что вы полностью честны со своей работой. Ты не обманывал и не занимался плагиатом ни одной своей работы, все это твоими собственными словами. Знание того, что вы можете выполнять работу самостоятельно, означает, что вы понимаете, чему вас учат, и действительно стараетесь узнать больше. Вы должны быть в состоянии выполнить любые задания, экзамены и любые другие заданные задания с полной честностью.

Профессора колледжа и преподаватели колледжа хотят, чтобы студенты были честны с работой, которую они представляют. Если они делают это своими словами, то они знают, что студенты могут учиться и понимать работу, которой они научили. Академическая добросовестность является основным ядром обучения. Чем больше вы росли в школе, тем больше вы росли как личность. Чем больше вы узнаете, тем больше вы узнаете о вещах, о которых вы никогда не думали раньше. Он ценит избегание таких вещей, как мошенничество или плагиат. Некоторые способы, которыми студенты нарушают академическую честность, – это когда они обманывают. Они смотрят на чужую газету или копируют свои работы, когда сами не делали. Когда человек обманывает, это показывает, что он ничего не узнал. Они полагаются на чужое слово, чтобы помочь им. Но это оставляет их с некоторым дискомфортом или стыдом. Они теряют некоторое уважение к себе, и это беспокоит их до тех пор, пока они не признаются, но большинство людей не в состоянии обманывать, пока их не поймают.

<Р>

Политика Morehead по академической честности и плагиату почти такая же, как и у всех колледжей в штате. Если мы здесь проявим академическую нечестность, то это решение профессора о том, каким должно быть наказание. Будь то провал этого задания, провал этого класса или исключение из этого класса на оставшуюся часть семестра или любое другое время в колледже. Я согласен с политикой, потому что, если вы не можете выполнять свою собственную работу, вы действительно ничего не можете сделать самостоятельно. Вы должны быть в состоянии написать статью своими словами или большую часть своими словами и отдать должное тому, что не принадлежит вам.

Зарегистрируйся, чтобы продолжить изучение работы

30.10.2020

Комментариев нет

Статья Джеральда Граффа «Скрытый интеллектуализм» взята из его книги 2003 года «Невежественный в учебе: как школьное обучение затмевает жизнь разума». В статье Graff критикуется подход

Читать полностью »

28.10.2020

Комментариев нет

Мой интерес к изучению бизнеса возник во мне, когда… я знаю, что извлеку из этого пользу, как я всегда хотел, с точки зрения изучения того,

Читать полностью »

27.10.2020

Комментариев нет

Целью данного эссе является предоставление реалистичного и всестороннего анализа «Case Study: Bryanna» с применением 10-ступенчатого процесса специального образования, как это предусмотрено федеральными правилами IDEA при

Читать полностью »

Что такое академическая честность и зачем она нужна?

- Подробности

- Опубликовано: 19 сентября 2019

Почти каждый из нас, когда-нибудь так или иначе страдал из-за непрофессионализма тех или иных специалистов. Иногда такое ощущение, что некоторые даже в школе не доучились. Особенно страшно если непрофессионалы это врачи, несущие за жизнь человека ответственность во время операций или строители которые спустя рукава делают чертежи зданий, лишь бы быстрее сдать объект. Не задумываясь о том, что это здание может рухнуть и сколько в нем окажется людей. Не редкость такое и среди недобросовестных преподавателей, учителей которые просто могут разрешить сидеть в телефоне до конца занятия. Лишь бы было тихо, уходя при этом по своим делам. Тем самым порождая таких же нерадивых работников в будущем. И многие другие, таких примеров множество почти во всех отраслях. Но все, как известно, начинается с малого.

Причины возникновения академической нечестности

Существует несколько видов академической нечестности:

Плагиат:

Присвоение или воспроизводство идей, слов или утверждений другого человека без соответствующей отсылки.

Фабрикация:

Фальсификация данных, ссылок или любой другой информации, связанной с академическим процессом.

Обман:

Предоставление ложной информации преподавателю или коллегам, например, ложная причина пропущенного урока или ложное утверждение, что работа была сдана.

Списывание:

Любая попытка использования внешней помощи без соответствующего на то разрешения, либо без признания использования этой помощи.

Саботаж:

Действия, направленные на то, чтобы помешать другим выполнять свою работу или полностью остановить работу других. К таким действиям относятся вырывание страниц из библиотечных книг или прерывания проведения экспериментов других лиц.

В наше время существуют три главных проблемы, дающих толчок академической нечестности: непрофессионализм, падение общественного культурного уровня и пиратство. В современном Казахстане, большинство населения привыкло к плагиату и списыванию, забывая про свой профессиональный опыт. Именно из-за таких рабочих происходят несчастные случаи.

Так что же такое академическая честность и зачем она нужна?!

Академическая честность — совокупность ценностей и принципов, которые развивают личную честность в обучении и оценивании. Также может трактоваться, как достойное поведение при выполнении письменных контрольных работ, экзаменов, эссе, исследований, презентаций.

Академическая нечестность оказывает негативное влияние на формирование личности ученика. Большинство людей настолько привыкло к этому, что не обращает внимание на данную проблему и старается ее игнорировать. Ниже приведены возможные пути решения данной проблемы.

Методы борьбы с академической нечестностью

Самоконтроль: Ученики должны быть с ранних лет обучены контролировать себя и свою деятельность, не давать списывать и не списывать самим. Махатма Ганди говорил: «Хочешь изменить мир — начни с себя».

Увеличение количества вариантов с заданиями:

На проверочные, самостоятельные и контрольные работы необходимо выдавать не несколько вариантов с заданиями, как это принято, а столько вариантов, сколько учеников в классе. Это лишит ученика возможности списать и будет способствовать самостоятельному выполнению того или иного задания.

Лишение ученика возможности списать:

Усиление наблюдения за учениками во время сдачи экзаменов. Установка видеокамер в каждом классе, блокировка мобильных телефонов и т. д.

Замена тестовых заданий устными:

При замене тестовых заданий устными потребность списывать отпадет сама собой.

Регулярные беседы с учениками:

Профилактические беседы с учениками на тему академической честности на регулярной основе. Усиление влияния путем рассказа о том, к каким последствиям может привести академическая нечестность и как она скажется на будущем учащихся.

Дмитрий ПЕТРЕНКО —

Пресс-секретарь КГПУ им. У. Султангазина

Академическая честность — это моральный кодекс или этическая политика.

Академическая честность поддерживает соблюдение образовательных ценностей посредством таких действий, как предотвращение мошенничества, плагиата и мошенничества по договоренностям, а также поддержание академических стандартов: честность и строгость.

Академическая честность:

Соблюдение принципов

– Честности

–Доверия

– Справедливости

– Уважения

–Ответственности

Академическая честность означает делать правильные вещи, даже когда никто не смотрит.

– Создание и выражение собственных идей в письменных работах

– Признание всех источников информации

– Выполнение заданий самостоятельно или подтверждение сотрудничества

– Точное представление результатов при проведении собственных исследований или в отношении лабораторий

– Честность во время экзаменов

• Это соблюдение академических правил и норм честности, установленных образовательным учреждением.

• Они помогают студентам и преподавателям принимать ответственные, моральные и этические решения, связанные со всеми аспектами их взаимодействия с университетом.

Ключ к успеху?

• Академическая нечестность не только лишает студента в получении знаний, но и может привести к провалу оценки на заданиях, провалу оценки на курсе или даже отчислению студента из Университета.

• Умение выражать оригинальные идеи, цитировать источники, работать самостоятельно, точно и честно сообщать о результатах — это навыки, которые необходимы студентам даже после завершения из академической карьеры

Виды академической нечестности

• Плагиат, самоплагиат

• Списывание ответов тестов

• Выполнять чужую работу

• Давать кому-то ответы на вопросы теста или экзамена, или получать ответы от кого-то заранее

• Платить кому-то, чтобы он сделал задание за тебя

• Саботаж • Мошенничество

• Подделка (forgery)

• Фальсификация

• Изготовление (fabrication)

• Содействие академической нечестности

• Несанкционированное сотрудничество

Плагиат

• Представление чужих работ или идей как своих собственных.

–Идея, мысли;

–Язык, прямые цитаты, фразы

–Структура, организация

• Студенты должны приписывать все, что они используют, что не является их собственным и ссылаться на источник

Интернет

– Студенты быстро поняли, что могут избежать написания статей, если просто скопируют то что им нужно из Интернета.

– Только в 2000 году Turnitin.com был запущен.

Примеры нарушений (плагиат)

• Покупка работ онлайн

• Копирование и вставка из интернета

• Перестановка слов и предложений

• Использование информации без ссылки на источник

• Повторное использование работы

Обман

• Списывание

• Повторное сдача уже оцененной работы

• Ложные оправдания в случае невыполнения или несвоевременного выполнения заданий

• Представление чужих работ как своих собственных

Обман по контракту (contract cheating)

• Практика привлечения сторонних людей для выполнения заданий.

• Когда кто-то, кроме студента, выполняет задание, и этот студент затем представляет его для оценки / зачета. – Студенты обмениваются заданиями – Студент просит друга или члена семьи помощи – Студент скачивает задание из «бесплатного» эссе сайта

Академическая честность это проблема сообщества

• Академическая честность — ответственность каждого – Работать вместе как сообщество желательно, чтобы каждый был подотчетен, поддерживал высокие стандарты и сохранял ценность получаемой степени.

• Человек, который помогает другим нарушать политику, также виновен и может быть привлечен к ответственности.

• Если какой-либо студент не сообщает об известном нарушении, он может быть привлечен к ответственности.

Санкции

• Варьируются от колледжа к колледжу и, конечно же, от нарушений.

• Вот некоторые из возможных вариантов: – Провалить задание или тест – Полное отстранение от курса – За серьезные или повторные нарушения,

• Наложение санкций испытательного срока (любые новые нарушения приведут к более серьезным санкциям)

• отстранение (придется семестр или более не посещать занятия) • или исключение (не могут вернуться)

Подборка по базе: 3. Ich möchte was essen.pdf, _АКАДЕМИЧЕСКАЯ ЧЕСТНОСТЬ.docx, кл Честность.docx, 2 essey.docx, 1 essey.docx, +Статья Академическая мобильность.docx, Panova Karinochka ESSE.docx, Конспект урока Тема_ ЧЕСТНОСТЬ И СПРАВЕДЛИВОСТЬ.docx, Zaharov D A Esse.docx, Family is one of the most essential aspects of life.pdf

Академическая честность — совокупность; ценностей и принципов, выражающих честность студента в обучении при выполнении письменных работ (контрольных, курсовых, эссе, дипломных, диссертационных), ответах на экзаменах, (в исследованиях, выражении своей позиции, в взаимоотношениях с академическим персоналом, преподавателями и другими студентами, а также оценивании).

Виды нарушений

Настоящими правилами предусматриваются следующие виды нарушений академической честности обучающимися, преподавателями и сотрудниками университета:

1) плагиат:

— частичное либо полное присвоение материалов из других источников без предоставления подтверждения авторства или указания источника;

Плагиат может проявляться в различных формах:

• цитирование источника без использования соответствующей пунктуации (кавычек) и/или без указания источника;

• перефразирование источника без указания источника;

• использование чьих-либо идей или аргументов без ссылки на автора;

• представление письменной работы, написанной полностью или частично другом или другим студентом;

• представление курсовой / дипломной работы, взятой из Интернета;

• представление курсовой работы, которая была выполнена как задание для другого курса.

2) сговор:

— выполнение любой оцениваемой работы за другого учащегося;

3) обман:

-списывание оцениваемых работ у других обучающихся;

— повторное предоставление, сдача уже оцененной работы;

— представление ложных оправданий в случае невыполнения, несвоевременного выполнения оцениваемых работ;

— выполнение оцениваемой работы двумя или более учащимися, в которой не предусматривается групповая работа;

— осознанная помощь другим учащимся: позволение списывать ему/ей со своей оцениваемой работы, подсказки, использование шпаргалок, учебников и т.д.

— представление чужих оцениваемых работ как своих собственных.

4) фальсификация оценок, данных оцениваемой работы:

— подделка оценок, результатов оценивания ответов к заданию;

— подделка данных (дописывание, вписывание, исправление), то есть измерений и результатов наблюдений опроса, анкетирования и других методов при выполнении исследования;

— завышение оценок контрольных письменных работ;

— намеренное подделывание или порча оцениваемой работы другогообучающегося;

5) приобретение ответов оцениваемых работ нечестным путем:

— передача ответов во время выполнения оцениваемой работы;

— получение частичного или полного материала до проведения оцениваемой работы с помощью другого учащегося, педагогического работника или сотрудника (тестовых заданий с ответами, экзаменационных билетов и заданий, заданий для письменного экзамена);

— покупка или иные пути получения оцениваемых работ для выдачи их как собственных (курсовых, дипломных работ, магистерских диссертаций и др.);

— продажа или иные пути помощи в покупке и/или продаже готовых оцениваемых работ (курсовых, дипломных работ, магистерских диссертаций и др.);

6) неправомерное использование информации или устройств:

— использование информации на электронных, цифровых, бумажных носителях, технических устройств во время выполнения контрольных оцениваемых работ, тестирования;

— получение любых ответов оцениваемой работы любыми путями, включая скачивание через электронную почту, компьютер и т.д.;

— вынос из кабинета и/или копирование с компьютера материалов педагогического работника, касающихся оцениваемых работ на бумажных и электронных носителях.

М.М. Рогожа

УДК 174:378.4 (045)

Академическая честность как этическая проблема

Аннотация. В статье рассматривается понятие академической честности и модусы актуализации академической честности как этической ценности в современном университете. Академическая честность показана как принцип этики добродетели, а конкретные примеры из университетской жизни дают возможность увидеть ее действенность в такой системе координат. Ведущая роль данного принципа в современной академической сфере показана в контексте актуализации третьей (после обучения и научного исследования) миссии университета — общественного служения — и произошедшей в ходе ее установления массовизации высшего образования.

Ключевые слова: академическая честность, университет, этика добродетели, добродетель, ценности студента.

В современном академическом дискурсе понятие академической честности постепенно занимает центральное место, отражая общую тенденцию университетской жизни активно апеллировать к ценностям, призывать членов академического сообщества следовать им. В украинской академической среде буквально за последний год был проведен ряд мероприятий, в центре которых оказывалась академическая честность.

Это Круглые столы и конференции: «Инновационный университет и лидерство: перспективы развития» (Одесский государственный экологический университет, июль, 2015); Украинско-польская международная научная конференция «Классический университет в контексте вызовов эпохи» (Киевский национальный университет имени Тараса Шевченко, сентябрь, 2016);

Исследовательские и образовательные проекты: Польско-украинский проект «Инновационный университет и лидерство» (2014-2016); «Проект содействия академической добродетели в Украине (SAIUP)». Социологическое исследование Восточно-

украинского фонда социальных исследований совместно с Институтом социально-гуманитарных исследований Харьковского национального университета имени В. Н. Каразина «Академическая культура студенчества: основные факторы формирования и развития»; «Осенняя школа исследовательских методов и академического письма в социально-гуманитарных науках (платформа «Осв™ тренди», сентябрь, 2016). В этот же ряд можно поставить и создание подкомиссии «Академическая добродетель» в составе научно-методической комиссии Министерства образования и науки Украины, а также публикацию и широкую презентацию в академической среде коллективной монографии «Академическая честность как основа устойчивого развития университета» [1].

Собственно, в научный дискурс понятие академической честности было привнесено американскими учеными, с 1990-х годов активно обсуждающих проблематику academic integrity. На постсоветском пространстве в этико-прикладном ключе вопросы integrity как общей проблемы честности поднимались на страницах специализированных изданий [5, 10, 11, 12, 13]. Термин переводился преимущественно как «честность», но сама его многозначность обуславливала необходимость указания англоязычного оригинала в скобках рядом с русским переводом. Только Р. Г. Апресян в реферате работы по академической этике дает перевод integrity как «добросовестность» [3], хотя годом ранее этот же термин он переводит как «честность», применительно к политической сфере [2]. Оксфордский словарь разъясняет значения слова integrity: качество быть честным и иметь твердые моральные принципы, моральная прямота [22]. Когда Апресян предлагает свой перевод, он указывает на смыслы, соотносимые с вышеуказанными: «Integrity — это, конечно, целостность, но также и честность, искренность, прямота; в специфическом этико-прикладном аспекте — добросовестность» [3, 228].

Добросовестность — это честность при выполнении обязательств, обязанностей [16, 150]. В толковом словаре В. Даля среди значений слова «добросовестность» указываются «благонамеренность» и «строгая богобоязненность в поступках» [14, 445]. В целом, речь идет о качествах честности, правдиво-

сти, твердости, возникающих в условиях осознанного следования взятым и/ или возложенным обязательствам. Необходимо обратить внимание на второй корень слова «добросовестность» — «совесть». Это традиционное для этической теории понятие, характеризующее «способность личности осуществлять моральный самоконтроль, самостоятельно формулировать для себя нравственные обязанности, требовать от себя их выполнения и производить самооценку совершаемых поступков» [17, 312]. Речь идет о том, чтобы осознавать и оценивать собственные действия. Если мы говорим об academic integrity, то предполагаем обязательность, добросовестность в академической среде. Останавливаясь на общепринятом словоупотреблении «академическая честность», следует иметь в виду весь очерченный здесь комплекс смыслов с акцентуацией смыслов добросовестности.

Для дальнейшего продвижения в этой теме следует указать и традицию, сложившуюся в украиноязычной академической сфере в отношении перевода термина academic integrity -«академiчна доброчеснють» (академическая добродетель). Здесь можно отчетливо увидеть отсылку академической честности как добросовестности к этике добродетели. Нет оснований считать такую связку намеренной. Скорее, свою роль сыграли смыслы «добро» и «честность», составляющие украинское слово «добродетель» и в таком своем качестве выходящие на указанные выше значения academic integrity.

На связь академической честности и этики добродетели специально указывает в своем реферате Р.Г. Апресян: «На основе этики добродетелей и вырастает концепция добросовестности (integrity), посредством которой на первый план в деятельности учебных заведений вместо «правил и регулятивов» выдвигаются добродетели, которые рассматриваются как должная база принятия решений и оценки деятельности» [3, 231].

Добродетели — это такие моральные качества личности, которые формируются и развиваются в рамках определенной практики. Исследователи этики добродетели вскрывают дея-тельностный характер моральных качеств: «Участвуя в практиках, человек развивает в себе как специфические личностные качества, необходимые для достижения внутренних целей-благ

конкретных практик, так и коммуникативные качества, необходимые для взаимодействия с другими участниками практики, вне которого осуществление практики невозможно» [4, 443]. В рамках практики формируется система норм и принципов, которые индивиды осваивают и развивают в процессе деятельности.

В свете этого этические кодексы представляют собой своды норм и ценностей в духе этики добродетели. В них академическая честность выведена основополагающим принципом деятельности в академической практике.

Рассмотрим принцип академической честности, сформулированный в этическом кодексе Европейского университета-института во Флоренции (European University Institute, учебное заведение высшего университетского уровня и исследовательский центр подготовки специалистов гуманитарного профиля для работы в структурах Европейского союза [15]). Академическая честность в этом документе [20, 8-9] определена в терминах (добродетелях) правдивости, доверия, честности, уважения, ответственности, законности. Она выступает в качестве метапринципа, каждый из параметров которого определяется соответствующими требованиями. Правдивость основана на требовании добывать знания, быть включенными в поиск истины, а также быть интеллектуально честными в изучении, обучении и исследовании. Доверие задается требованием формирования атмосферы взаимного доверия путем поддержки свободного обмена идеями и возможностью реализации своего академического потенциала. Честность основывается на требованиях создания прозрачных институциональных норм и процедур, а также налаживания взаимодействия между членами академического сообщества. Уважение как добродетель связана с требованием (взаимо)уважения студентов, профессорско-преподавательского состава и персонала во имя познания, образования и интеллектуального наследия. Ответственность задана требованием поддержания норм поведения в академической среде. Законность предполагает соблюдение действующих правовых норм в отношении авторского права, прав интеллектуальной собственности третьих сторон, средств и условий, регулирующих доступ к исследовательским ресур-

сам, а также клеветы. Нужно отметить, что в таком свете добродетель законности/ законопослушности задает этическую установку: морально быть законопослушным.

Если вести речь об академической честности в контексте этики добродетели, то закономерно и наличие методических пособий/ рекомендаций по совершению правильных поступков, организации правильной деятельности в рамках практики. Примером такого методического пособия является «Руководство для студентов по академической честности в Массачусетском технологическом институте (Massachusetts Institute of Technology)» [19], в котором даны подробные разъяснения целей и задач следования принципам академической честности и правдивости, а также подробно описаны случаи их нарушения. Формулировки и способ изложения даны предельно четко и понятно.

Например, в параграфе «Что такое академическая честность?» [19, 3] советы даны таким образом, что побуждение к конкретному действию сопряжено с запретом противоположного.

Так, во-первых, вопрос плагиата ставится следующим образом:

1. «Делай: Верь в ценность собственного ума».

«Не делай: Не приобретай письменные работы и не принуждай кого-либо писать работу для тебя».

2. «Делай: Проводи исследования честно и уважай других за их работу».

«Не делай: Не копируй идеи, данные и точные формулировки без цитирования источника».

Во-вторых, предлагается вопрос о несанкционированном сотрудничестве:

«Делай: Думай своим умом».

«Не делай: Не сотрудничай с другим студентом сверх меры, определенной преподавателем».

В-третьих, уделено внимание вопросам мошенничества.

1. «Делай: Демонстрируй свои собственные достижения».

«Не делай: Не копируй ответы другого студента; не проси другого студента сделать вместо тебя твою работу. Не подделывай результаты. Не используй электронные или иные приспособления во время экзаменов».

2. «Делай: Принимай исправления преподавателя как часть учебного процесса».

«Не делай: Не изменяй оценки экзаменов и не подавай их на пересдачу».

3. «Делай: Готовь оригинальную работу для каждого занятия».

«Не делай: Не подавай проекты или письменные работы, подготовленные для предыдущего занятия».

В-четвертых, по проблеме содействия академической нечестности указано:

«Делай: Демонстрируй собственные способности».

«Не делай: Не позволяй другому студенту копировать твои ответы на проверочных работах или экзаменах. Не сдавай экзамен или проверочную работу за другого студента».

Далее в «Руководстве» подробно объясняется, что такое плагиат и указываются конкретные шаги, которые необходимо предпринять во избежание обвинений в плагиате; разъясняется, как и какие нужно использовать электронные источники и как правильно их цитировать. Подчеркивается, что академическое письмо — неотъемлемая часть академической честности, и приводятся конкретные примеры корректного избегания плагиата путем переформулировки. Даются разъяснения моделей сотрудничества студентов в учебном процессе и приводятся примеры недопустимого взаимодействия. Подается список мошеннических действий в учебном процессе, например, изготовление копий письменных работ, подделка подписей, помощь другому студенту в аморальных действиях в учебном процессе и т.п. В результате освоения материала этого методического пособия студент должен составить внятное представление о том, что такое академическая честность, как ее достичь и практиковать, и каковы морально недопустимые действия в этой сфере.

В недавно опубликованном «Пособии по академической честности» авторы, признанные специалисты в данной проблематике, отмечают, что гораздо эффективнее не давать перечень запретов, описание санкций и примеры наказаний, а показывать и разъяснять конкретные правильные поступки, побуждать индивида к моральному действию [21, 16].

Такого рода подробные инструкции кодексов и методических пособий — яркие, но не единичные примеры нравоучительных текстов в академической сфере. Возникают закономерные вопросы: Почему стало необходимым разъяснять так подробно, казалось бы, очевидные вещи? Почему академическая честность стала ценностью, которую вменяют в обязанность так настойчиво и последовательно?

Ответы следует искать в ценностных сдвигах, произошедших в современном университете. Закрепившееся со времени становления Гумбольдтовского университета единство обучения и исследования претерпевает сегодня существенные содержательные изменения, сопряженные с ценностными трансформациями. Университетская миссия прирастает деятельностью «во благо общества». Стейкхолдеры вместе с профессионалами обсуждает возможности университета быть полезным обществу, реагировать на ожидания общественности. Направленность университета на запросы общества изменяет социальные роли преподавателя и студента. Приоритет переходит от того, кто обучает, к тому, кто получает знания, ориентируясь на рынок труда и дальнейшую трудовую деятельность после университета [8, 141-142]. Эта тенденция тем более заявляет о себе, чем сильнее общество нуждается в работниках со специальными знаниями, навыками, получивших специальную профессиональную подготовку, которую может обеспечить нынешний университет.

Неотъемлемой чертой современности становится массовость высшего образования. Эта особенность была озвучена на Международной конференции по этическим и моральным изменениям в высшем образовании и наук в Европе (Бухарест, сентябрь, 2004). В итоговом документе конференции, «Бухарестской декларации по этическим ценностям и принципам высшего образования в европейском регионе» (2004), в преамбуле было указано: «Университеты отвечают не только за формирование будущих профессиональных, технических и социальных элит; они теперь обучают массовые студенческие контингенты» [9]. Это гораздо раньше предельно четко выразил У. Эко: «В былое время университеты были элитарными. Туда поступали дети тех, кто сам кончал университеты… У нас образование но-

сит массовый характер. В университеты идет молодежь любых социальных слоев, после каких угодно школ» [18, 6].

Охват широких слоев населения высшим образованием меняет критерии отбора абитуриентов: неизбежно снижается планка требований к уровню их подготовленности к учебе в университете. Это касается, в первую очередь, моральных качеств, которые необходимы для университетской жизни и которые, в свою очередь, укрепляются и развиваются в ходе обучения в университете. Например, в отчете Йельского университета за 1828 г. было указано, что моральное развитие личности является одной из целей получения высшего образования. Такая постановка вопроса была задана религиозной составляющей в университетской жизни. Преподавательский состав укомплектовывался священниками, а студенческий контингент видел свою миссию после окончания университета в духовной деятельности [21, 8-9].

Эту же тональность отмечал и Г. С. Батыгин. Он констатировал, что первыми профессионалами в Европе были люди, чья деятельность связана с миром университета: «Первоначальный смысл слова «профессия» заключается в открытом заявлении о принятии монашеского обета… Профессионалы… не работают, а служат: они отдали себя делу и ничего не просят взамен» [6, 6]. Это имел в виду и Ж. Бенда, когда писал об интеллектуалах, живущих высшими духовными ценностями, занимающихся бескорыстной умственной деятельностью и видящих свою миссию в сохранении неутилитарных ценностей [7, 76].

Именно такая установка традиционно принималась и воспроизводилась в университетской среде, как на уровне университетских интеллектуалов, так и в процессе обучения — студентами, которые готовились сами стать университетскими интеллектуалами, или профессионалами: юристами, медиками, священниками, позднее — инженерами. Дух профессионального служения, ориентированность на высокие этические стандарты были основой системы ценностных координат в мире университета.

Ориентированность современного университета на запросы общества, которое нуждается в массах квалифицированных (специально обученных) работников ведет к массовизации

высшего образования. В таких условиях невозможно сохранить пафос учебного процесса как морального совершенствования личности. Поэтому мы не только наблюдаем, но зачастую и активно участвуем в институционализации ценностно-нормативной составляющей университетской жизни. Так и получается, что очевидные ценности — взаимоуважения, доверия, справедливости, научной честности, равно как и способность личности осознавать свои моральные обязанности по отношению к учебному процессу, научному знанию и взаимодействию в академической среде — перестали быть сами собою разумеющимися, а оказались предметом специальных этико-нормативных действий. Целью создания, внедрения и продвижения этической инфраструктуры (в данном случае, этических документов — кодексов, методических рекомендаций) является необходимость обеспечить соблюдение традиционных этических норм университетской жизни преимущественно мягкими обязывающими средствами.

Список литературы

1. Академiчна чеснють як основа сталого розвитку уывер-ситету /за аг. ред. Т. В. ФУкова, А. G. Артюхова. К.: Таксон, 2016. — 234 с.

2. Апресян Р. Г. Политическая этика в Канаде (по материалам ресурсов Интернета) // Политическая этика: социокультурный контекст. Ведомости. Вып. 24 / Под ред. В.И.Бакшта-новского, Н.Н.Карнаухова. Тюмень: НИИ ПЭ, 2004. С. 256-267.

3. Апресян Р. Г. Macfarlane B. Teaching with Integrity; the Ethics of Higher Education Practice. L.-NY: Routledge Falmer, 2004. — 184 p. (реферат Р. Г. Апресяна) // Этика образования. Ведомости. Вып. 26 / Под ред. В.И.Бакштановского, Н.Н.Карна-ухова.Тюмень: НИИ ПЭ, 2005. С. 228-238.

4. Артемьева О. В. Теоретические основания этики добродетели // Философия и этика: сборник научных трудов. К 70-летию академика А. А. Гусейнова. М.: Альфа-М., 2009. С. 433445.

5. Бакштановский В. И., Согомонов Ю. В. Ноу-хау как способ существования прикладной этики: по мотивам эксперти-

зы концептуальной модели университетского кодекса // Этический кодекс университета. Ведомости. Вып. 34 / Под ред. В.И. Бакштановского, Н.Н. Карнаухова.2009. Тюмень: НИИ ПЭ. С. 158-246.

6. Батыгин Г. С. Профессионалы в расколдованном мире // Этика успеха: Вестник исследователей, консультантов и ЛПР. Вып. 3. Тюмень — Москва, 1994. С. 6-11.

7. Бенда Ж. Предательство интеллектуалов. М.: ИРИСЭН, Мысль, Социум, 2009. — 310 с.

8. Брызгалина Е. В. Болонский процесс: трансформации ценностей в системе образвания // Этическое регулирование в академической среде: Материалы международной научно-практической конференции / МГУ им. М. В. Ломоносова, 4-5 декабря 2009. М.: МАКС Пресс, 2009. С. 138-143.

9. Бухарестская декларация по этическим ценностям и принципам высшего образования в Европейском регионе (2004). CEPES, Бухарест. URL http://www.sde.ru/files/t/pdf/2.pdf / (дата обращения: 14.11.2016).

10. Васильевене Н. Доверие и стратегии его укрепления средствами этики // Со^альна етика:Теоретичн i приклады про-блеми. Зб. наук.ст. К.:Уыверситет «Укра’|’на», 2012. С. 33-46.

11. Васильевене Н. Институционализация деловой этики: инструментальное внедрение ценностей в деятельность организаций // Прикладная этика: «КПД практичности». Ведомости. Вып. 32. Тюмень, 2008.С. 82-107.

12. Васильевене Н. «… Профессиональная и организационная этики должны усиливать друг друга, а не противостоять» (интервью Н. Васильевене В. И. Бакштановскому) // Этический кодекс университета. Ведомости. Вып. 34 / Под ред. В.И. Бакштановского, Н.Н.Карнаухова, Тюмень, 2009. С. 139-145.

13. Васильевене Н. Этика в деле формирования корпоративной ответственности //Со^альна етика: модуси вщповщаль-носД Мiжнародна наук.-практ.конф. (2010 ; Кив) /редкол. А. G. Конверський [та Ы.]. К.: ВП КиТвський уыверситет, 2011. С. 92-108.

14. Даль В. Толковый словарь живого великоруського язи-ка в 4т. Т. 1. М.: Русский язик, 1989. — 699 с.

15. Морозова М. Европейский университет-институт во Флоренции// Европейский альманах. История. Традиция. Культура. М.: Наука, 1993. С. 170-174.

16. Ожегов С. И. Словарь рус^ого языка/ под ред. Н. Ю. Шведовой. Изд. 14-е, стереотип. М.: Русский язык, 1983. — 816с.

17. Словарь по этике /Под ред. И. С. Кона. 4-е изд. М.: Политиздат, 1981. — 430 с.

18. Эко У. Как написать дипломную работу. Гуманитарные науки: учеб-метод. пособие. 2 изд. М.: Книжный дом «Университет», 2003. — 240 с.

19. Academic Integrity at MIT. A Handbook for Students/ P. Brennecke. MIT Press, 2016. — 36 p.

20. Code of Ethics in Academic Research European University Institute URL http://www.eui.eu/Documents/ServicesAdmin/De-anOfStudies/CodeofEthicsinAcademicResearch.pdf/ (accessed 14.11.2016).

21. Handbook of Academic Integrity /ed. by T. Bretag. Springer Reference, 2016. 1097 р.

22. Integrity // English. Oxford Living Dictionaries URL http: en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/integrity(accessed 14.11.2016).

- Review

- Open Access

- Published: 15 April 2021

International Journal for Educational Integrity

volume 17, Article number: 8 (2021)

Cite this article

-

11k Accesses

-

12 Citations

-

12 Altmetric

-

Metrics details

Abstract

This conceptual review seeks to reframe the view of academic integrity as something to be enforced to an academic skill that needs to be developed. The authors highlight how practices within academia create an environment where feelings of inadequacy thrive, leading to behaviours of unintentional academic misconduct. Importantly, this review includes practical suggestions to help educators and higher education institutions support doctoral students’ academic integrity skills. In particular, the authors highlight the importance of explicit academic integrity instruction, support for the development of academic literacy skills, and changes in supervisory practices that encourage student and supervisor reflexivity. Therefore, this review argues that, through the use of these practical strategies, academia can become a space where a culture of academic integrity can flourish.

Introduction

In the contemporary higher education environment, issues of academic integrity and credibility are turning matters of learning into matters of surveillance and enforcement. Increasingly, higher education institutions are relying on text-matching software (such as Turnitin) and the monitoring or scrutiny of students (e.g., through practices such as online proctoring) as a proxy to measure their level of academic integrity (Dawson 2021). Indeed, failure to adhere to these often contextually and socially constructed rules of academic integrity is termed academic misconduct or dishonesty and can lead to severe consequences for students. As Dawson (2021) notes, this approach is adversarial, focussing on detection rather than encouraging academic integrity. This adversarial approach is also reflected in recent changes to Australian federal legislation (see the Prohibiting Academic Cheating Services Act 2020), with provision of an academic cheating service now attracting criminal or civil penalties. There is also increasing concern about the “threats to academic integrity [ …] due to the wide-spread growth of commercial essay services and attempts by criminal actors to entice students into deceptive or fraudulent activity” (Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) 2021 para. 2 emphasis added). Despite this often adversarial language, however, TEQSA also acknowledges that there is a need to promote academic integrity practices by, for example, working with experts to create an Academic Integrity Toolkit (TEQSA 2021).

Interestingly, the higher education environment now appears to lead educators to a dichotomous choice to either be “pro-integrity” or “anti-cheating” (Dawson 2021 p. 3). In this conceptual review, we seek to challenge this perception. We focus on how doctoral education programs can foster academic integrity skills development to create an environment where policies and surveillance strategies are incorporated into pedagogical practice. East (2009) highlights the importance of viewing academic integrity development as a holistic and aligned approach that supports the development of an honest community within the university. Furthermore, Clarence (2020) argues that doctoral education is underpinned by the axiological belief that graduates should be confident scholars who value integrity in research, authenticity, and ethics. Therefore, it is our argument that it is the responsibility of educators to explicitly teach these skills as part of doctoral education programs in order to encourage a culture of academic integrity among both staff and students (see, for example, Nayak et al. 2015; Richards et al. 2016). The long-term benefits of such a culture of academic integrity will include greater awareness of academic integrity for both staff and students, the involvement of students in creating and managing their own academic integrity, a reduction in academic integrity breaches, and improved institutional reputations (Richards et al. 2016).

Contextualising our review within the Australian higher education setting, our view of academia is representative of an all-encompassing global space which welcomes the skills, knowledge, values, and practices of all scholars regardless of their background. In this review, we highlight how practices within academia create an environment where feelings of inadequacy thrive, leading to behaviours of unintentional academic misconduct. In particular, we explore the impact of the imposter phenomenon and cultural differences on academic integrity practices in doctoral education. We conclude this review by providing practical suggestions to help educators and institutions support doctoral student writing in order to avoid forms of unintentional academic misconduct. Therefore, in this review we argue that, through the use of these practical strategies, academia can become a space where a culture of academic integrity can flourish.

Key concepts in academic integrity

As Bretag (2016) stresses, definitions of integrity terms matter, as researchers have previously fallen into the trap of synonymously linking concepts together. The notion of academic integrity is multifaceted and complex, so defining the concept is an ongoing and contestable debate amongst researchers (Bretag 2016). In general, academic integrity is considered the moral code of academia that involves “a commitment to five fundamental values: honesty, trust, fairness, respect, and responsibility” (International Center for Academic Integrity 2014 p. 16). Therefore, we consider academic integrity as a researcher’s investment in, and commitment to, the values of honesty, trust, fairness, respect, and responsibility in the culture of academia. In this review, we adopt the following interpretation of academic integrity (Exemplary Academic Integrity Project 2013 section 15 para. 2):

Academic integrity means acting with the values of honesty, trust, fairness, respect and responsibility in learning, teaching and research. It is important for students, teachers, researchers and all staff to act in an honest way, be responsible for their actions, and show fairness in every part of their work. Staff should be role models to students. Academic integrity is important for an individual’s and a school’s reputation.

An important component of academic integrity for doctoral students is integrity in the research process. We consider ethical research practice to involve conducting research in a fair, respectful and honest manner, and reporting findings responsibly and honestly.

In contrast, academic misconduct (also termed academic dishonesty) involves behaviours that are contrary to academic integrity, most notably plagiarism, collusion, cheating, and research misconduct. In this review, plagiarism refers to presenting someone else’s published work as your own without appropriate attribution. Drawing on the work of Fatemi and Saito (2020), we stress that plagiarism can be either intentional or unintentional. We consider intentional plagiarism as purposely using other people’s work and promoting it as your own. In contrast, we define unintentional plagiarism as not acknowledging another researchers’ ideas by, for example, forgetting to insert a reference, not inserting the reference for every sentence from a source, or placing the reference in the wrong place within the text (Fatemi and Saito 2020). In this review, collusion is defined as unauthorised collaboration with someone else on assessed tasks while cheating is defined as seeking an unfair advantage in an assessed task, including resubmission of work from another unit. Notably, academic settings have seen a rise in what has been termed contract cheating, where assignments are completed by outside actors in a fee-for-service type arrangement (Bretag et al. 2019; Bretag et al. 2020; Clarke and Lancaster 2006; Dawson 2021; Newton 2018). Finally, we consider research misconduct to be misrepresenting the study design or methodology, falsifying or fabricating data, and/or breaching ethical research requirements. Academic institutions often have a range of responses, policies, and procedures to identify academic misconduct; these range from official warnings to loss of marks on an assignment or expulsion from the institution for the most severe cases.

Academic integrity and the imposter phenomenon

It is important to note that, for this review, the authors have agreed upon the term imposter phenomenon, although the expression imposter syndrome is often used synonymously in the literature. The term imposter syndrome was initially coined by Clance and Imes (1978) to describe individuals who felt like frauds and perceived themselves as unworthy of their achievements, despite objective evidence to the contrary. To avoid stigmatisation of these feelings as a pathological syndrome, the term imposter phenomenon is more commonly used in modern thinking. Imposter phenomenon can therefore be defined as “the persistent collection of thoughts, feelings and behaviours that result from the perception of having misrepresented yourself despite objective evidence to the contrary” (Kearns 2015 p. 25).

This notion of feeling like a fraud is frequently experienced by doctoral students. Indeed, half (50.6%) of the PhD students in the study by Van de Velde et al. (2019) reported experiencing the imposter phenomenon. Similarly, Wilson and Cutri (2019) revealed how novice academics experienced constant disbelief in their success. This is because the imposter phenomenon is linked to an identity crisis which is commonly experienced by novice academics (Wilson and Cutri 2019). For instance, Lau’s (2019) autoethnographic reflection as a medical doctoral student highlighted how self-imposed pressures during his PhD journey led to feelings of inadequacy. This was due to a prevailing perception of what “the perfect PhD student” was and the feeling that he was not meeting this perceived standard, leading to self-sabotaging behaviours (Lau 2019 p. 52). Thus, from a doctoral student perspective, Lau (2019 p. 50) defines the imposter phenomenon as:

feelings of inadequacy experienced by those within academia that indicate a fear of being exposed as a fraud. These feelings are not ascribed to external measures of competence or success (e.g., publishing papers or winning prizes), but internal feelings of not being good enough for their chosen role (e.g., being a PhD student or academic staff member).

Lau (2019) warns that, if these feelings are left unchecked, it could lead to low self-confidence and high anxiety.

The imposter phenomenon is increasingly recognised as a significant issue by higher education institutions, but this is often considered a mental health concern affecting productivity and success (see, for example, University of Cambridge 2021; University of Waterloo 2021). It is important to note, though, that the feelings of fraudulence and negative self-confidence can be attributed to the socio-political and cultural environment of academia in which doctoral students are immersed. As Hutchins (2015) notes, the imposter phenomenon thrives in environments where there are expectations of perfectionism, highly competitive work cultures, and stressful environments. Academia is a high-stakes, competitive environment where a person’s success is measured by the quantity and quality of their research output, commonly referred to as an environment of publish or perish. Indeed, Moosa (2018) notes that academics must obey the rules of the publish or perish environment if they are to progress through their career. With an emphasis on scholarly dissemination, doctoral students are thrown into a new context of public critique through the peer review and publication process. While this is an opportunity for academics to showcase their research, Parkman (2016) notes that such public scrutiny invokes the common imposter phenomenon fear of being found out as a fraud. This is because doctoral candidates are constantly exposed to the final product, while the process of writing has been devalued (Wilson and Cutri 2019). The doctoral journey, however, should be about the process, as candidates are developing their skills and building their academic identities as future researchers in their fields.

When academic institutions focus on polished products, doctoral students who are currently engaged in the writing process feel a sense they are not good enough (Wilson and Cutri 2019). This is because the writing process and expectations at doctoral level are complex and challenging, requiring students to develop specific academic skill sets that are different from their previous studies (see Level 10 of the Australian Qualifications Framework for a list of the expected skills of doctoral graduates in Australia, Australian Qualifications Framework Council 2013). Facing these new challenges can be overwhelming and students compensate by engaging in sabotaging behaviours (such as procrastination, perfectionism, or avoidance) because they feel they must write like the experts in their field. Cisco (2020a) found that imposter phenomenon feelings became more prevalent with the challenge of these new and more complex academic tasks. This struggle during the reading and writing process can be attributed to a need for further development of the necessary academic literacy skills for a specific discipline. In this review, we consider literacy to refer to the socially constructed use of language within a particular context (Barton and Hamilton 2012; Lea 2004; Lea and Street 1998, 2006; Street 1984, 1994). Consequently, it is important to note that literacy is continuously constructed and includes elements of both power and privilege (Lea 2004; Lea and Street 1998, 2006). The term academic literacy skills, therefore, reflect a broad range of practices that are involved in the practice of communicating scholarly research (for example, learning the differences in academic writing for literature reviews, methodology, data analysis, and discussion of findings sections to answer the all-important so what question). These more advanced academic literacy skills are relatively new aspects for doctoral students, as the production of new knowledge is what makes a PhD candidature unique.

When doctoral students commence their studies, they transfer their prior understandings regarding appropriate academic conduct. Students enter doctoral training programs through a variety of pathways. For example, some students enter a PhD after completing an Honours degree, while others first complete a Masters or other graduate research degree. Increasingly, doctoral programs are also seeing students who return to study after several years away from university. Hence, students who enter doctoral studies, regardless of their prior educational experience, bring their discourses of academic understanding and what they perceive as appropriate with them.

It is likely that doctoral students have, at some point in their studies, encountered the concept of academic integrity at some level. While students may have encountered the concept of academic integrity in the past, this previous knowledge does not necessarily translate into an understanding of how to demonstrate academic integrity in their work at a doctoral level. There are also institutional and cultural differences that play a significant part in how academic integrity is applied in practice. Understanding how to apply this academic integrity knowledge in academic writing practice should, therefore, be considered a threshold concept – it is a concept which, when understood, leads to a permanent change of perspective (see Meyer and Land 2006). Pretorius and Ford (2017) describe threshold concepts as “gatekeepers to deeper knowledge, understanding and thinking [ …] that allow students to genuinely see new perspectives and think in different ways” (p. 151). Tyndall et al. (2019) notes that if doctoral students do not move across the threshold to understand how to apply academic integrity in their writing, it can lead to academic misconduct behaviours including mimicry and plagiarism.

Mimicking the sophisticated genre of academic writing seen in published works is often done in an effort to sound academic. The disciplinary discourse in which a person finds themselves contributes to the social construction of identity (Ivanič 1998). Furthermore, a person’s identity is inscribed in their writing practices (Ivanič 1998) – we write ourselves into our text as we interact with the social context in which we find ourselves. Ivanič (1998) notes that this discursive identity construction provides a useful lens through which to view academic integrity. Instead of condemning students for academic integrity breaches such as plagiarism, Ivanič (1998) argues that this type of behaviour can be seen as a function of “students’ struggles to achieve membership of the academic discourse community” (p. 197). For example, Fatemi and Saito (2020) note that, in the absence of appropriate academic literacy skills, postgraduate students can engage in what Howard (1992) termed patchwriting (i.e., poor paraphrasing, also termed source-reliant composition) where some words are synonymously replaced while the original sentence structure is maintained. While such an action is deemed as plagiarism, the students’ intentions are usually not to cheat but rather to try and write in what they perceive to be an academic style (Fatemi and Saito 2020; Pecorari 2003). Consequently, if doctoral students, engage in a form of academic misconduct other than contract cheating, we argue this is a form of unintentional academic dishonesty.

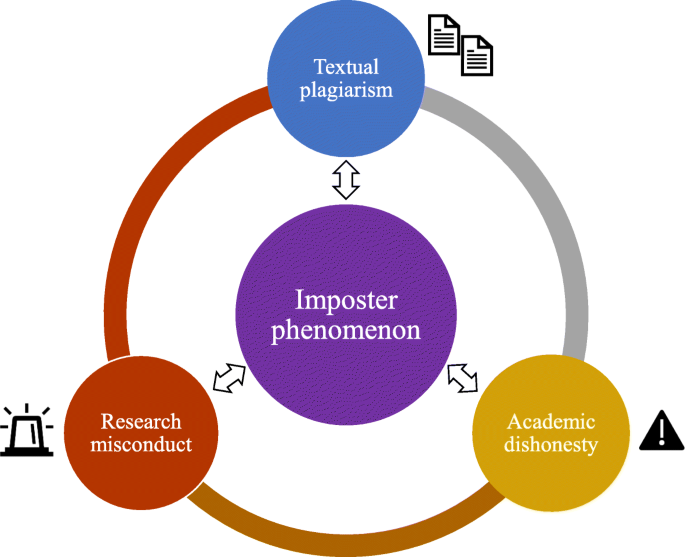

We have developed a model to highlight how the imposter phenomenon influences doctoral students’ academic integrity which we have termed the IPAIR model (the imposter phenomenon and academic integrity relationship model, see Fig. 1). We argue that feelings of being discovered as a fraud lead students to mimic academic practices, including textual plagiarism, academic dishonesty, and research misconduct (Fig. 1). The first component of this model, textual plagiarism, involves taking credit for another person’s published work without referencing the source, by providing inaccurate citation details, or by engaging in poor paraphrasing such as patchwriting. The second component, academic dishonesty, consist of the other elements of academic misconduct such as reusing previous work, collusion, and contract cheating. The final component of our model, research misconduct, includes misrepresenting the study design or methodology, falsifying or fabricating data, and breaching ethical requirements. It is important to note that the academic integrity breaches in our model are not necessarily intentional. Furthermore, it should be noted that the forms of academic misconduct highlighted in our model would also likely further exacerbate doctoral students’ feelings of inadequacy.

The Imposter Phenomenon and Academic Integrity (IPAIR) Model

Full size image

Academic integrity and cultural differences

We have argued that there is a relationship between the imposter phenomenon and academic integrity in relation to doctoral student writing. We further contend that cultural differences may impact academic integrity during a doctoral student’s candidature. In Australia, domestic and international students from a wide variety of cultural backgrounds study PhDs (see, for example, Cutri and Pretorius 2019; Pretorius and Macaulay 2021). In this paper we define a domestic student as someone who is an Australian or New Zealand citizen, or who holds a permanent residency or humanitarian visa. The term international student refers to someone who has a temporary visa to study in Australia. It is important to note that, in using the terms domestic and international, we do not intend to create a dichotomy between these student cohorts. Rather, these two terms can be considered representative of the often-times different sociocultural characteristics and power relationships that influence these students’ experiences (Cutri and Pretorius 2019; Pretorius and Macaulay 2021). It is also important to note that cultural differences exist between domestic students as well.

Today’s contemporary research context reflects a globalised academic landscape comprising expert, early career, and novice academics. The increase of internationally diverse doctoral scholars can be attributed to the process of globalisation (Cutri and Pretorius 2019). For this review, we have chosen to draw upon Holton’s (2005) definition of globalisation: “the intensified movement of goods, money, technology, information, people, ideas and cultural practice across political and cultural boundaries” (pp. 14–15). Globalisation has impacted higher education through an increased movement of international students which has also resulted in a higher number of international doctoral students enrolling at higher education institutions (Cutri and Pretorius 2019; Marginson and van der Wende 2007; Nerad 2010). In fact, many universities promote the mobility of higher education and offer scholarships for people around the world to continue their studies. This has led to the emergence of various cultural differences in expectations and understandings of academic integrity causing universities to reconsider their academic integrity practices and support structures for students.

Importantly, globalised movements describe not only people migrating from one country to another but also the movement of people’s ideas, beliefs and culture (see, for example, Appadurai 1990). Culture offers a lens through which people see and understand the world in which they live (Garcia and Dominguez 1997). Hence, culture includes “shared values, beliefs, perceptions ideals, and assumptions about life that guide specific behaviour” (Garcia and Dominguez 1997 p. 627). Hofstede et al. (2010) state that culture programs people’s behaviour, reaction and understanding and thus call it the “software of the mind” (p. 5). Culture is dynamic, persists over time, and, therefore, guides an individual’s capacity to make meaning of their world and experiences (Garcia and Dominguez 1997). Most importantly, Bourdieu (1984) argues that people can be unaware of their own cultural influences and how it shapes their decisions. Thus, the cultural practices, values and beliefs guiding an individual’s decisions appear natural and intuitive, but are in fact culturally driven. Consequently, culture plays a crucial role in influencing and guiding an individual’s decisions and meaning making capacity.

Cultural difference can be a leading cause for academic dishonesty amongst international postgraduate students as academic integrity has different definitions for different cultures (Velliaris and Breen 2016). This highlights that international postgraduate students may have different standards of academic integrity and plagiarism than the domestic students at their host universities. Students bring their pre-existing beliefs into academia while they, at the same time, grapple with newly formed expectations to be experts in their fields (see, for example, Cutri 2019). Indeed, as authors of this literature review, we found that we had several different pre-existing beliefs of academic integrity due to our own cultural backgrounds. For example, one of the authors of this literature review notes:

While in Australia, especially in doctoral studies, one of the key functions of an academic is to contribute to knowledge by identifying and filling gaps in existing knowledge. This requires advanced yet complex skills in reading existing literature, questioning the ontological and epistemological existence of knowledge along with arguing or critiquing studies respectfully. As an individual, who has experienced the [education system in my country] that worship textbooks, I find it extremely challenging to critique other studies and fail to recognise the limitations in the findings, methodology or methods employed in the study. Culturally, this practice of reviewing other academics work and addressing the limitations and gaps was not preached, experienced or expected. Therefore, I tend to use a lot of direct quotes from original writing.

As highlighted above, an array of cultural differences exists in understanding academic integrity. These differences in academic expectations can be wide-reaching, including a lack of language proficiency, as well as an unfamiliarity with the myriad of research and writing practices of their host universities (Cisco 2020a; Fatemi and Saito 2020). These differences can negatively affect postgraduate international students’ transition into academia, potentially leading to academic dishonesty (Fatemi and Saito 2020). It is, therefore, hardly surprising that Bretag et al. (2014) found that international students received three times more formal notifications of academic integrity breaches compared with domestic students. International students were also more than twice as likely to report feeling ill-prepared to avoid academic integrity breaches (Bretag et al. 2014).

Another factor resulting in a lack of academic integrity from international doctoral students is believed to be the lack of academic support for these students (Fatemi and Saito 2020). The transition from their home country’s academic integrity practices to those of their host country can also mean that not all skills brought by international postgraduate students are recognised by the host university. The transfer between one educational system to another combined with a lack of familiarity with the local academic integrity practices can result in unintentional academic dishonesty by international students (Fatemi and Saito 2020). Without appropriate support to develop academic skills from their universities, postgraduate international students can develop negative opinions about host countries and feel that their prior academic skills are devalued. It is, therefore, imperative that international postgraduate students adapt to local academic integrity practices with the support of universities. It is equally vital that local universities honour and value the pre-existing skills and beliefs of doctoral students and assist these students with building a new set of academic integrity practices.

Building academic integrity at a doctoral level

In the previous sections, we have highlighted the influence of the impostor phenomenon, a lack of academic literacy skills, and cultural differences on the academic integrity practices of doctoral students. Based on these factors, this section explores the multifaceted measures that could be put in place to better support doctoral students in developing academic integrity in their research and writing practices. In particular, we highlight the importance of explicit academic integrity instruction, support for academic literacy development, and changes in supervisory practices.

Explicit academic integrity instruction

The key to improved academic integrity practices at any level of study is the understanding of appropriate conventions in the discipline. Once PhD students are enrolled in their studies, many Australian universities provide mandatory training components related to academic integrity in research. At our institution, for example, all doctoral students are required to complete three online doctoral induction models that cover an introduction to the University, the Faculty, and research integrity. Across institutions, however, research integrity training is offered in a variety of formats and are focussed on many different areas of research ethics. Furthermore, there appears to be a presumption that, upon completion of these modules, doctoral students will understand their responsibilities and, therefore, not engage in academic misconduct. We argue that this presumption is dangerous and that doctoral students require ongoing scaffolding and skills development throughout their candidature. Furthermore, as highlighted in our model (see Fig. 1), research integrity involves a specific skill set. A lack of understanding of this skill set can lead to academic misconduct if students are not adequately supported. Löfström and Pyhältö (2017) highlight that doctoral students rely on their supervisors and faculty colleagues to help learn ethical guidelines and appropriate codes of conduct. By acknowledging that doctoral students unintentionally engage in academic misconduct due to a lack of awareness, universities can offer supportive structures and educational programs to help foster a deeper understanding of the impact of the imposter phenomenon, academic literacy skills, and ethical research approaches.

Bretag et al. (2014) highlight that postgraduate research students can be disadvantaged in terms of education, training, and support for academic integrity. This calls for institutions to provide interventions in the form of direct instruction at different stages of a doctoral program. Gullifer and Tyson (2014) have highlighted the need for universities to take proactive steps by offering formal workshops that highlight the expectations and strategies to maintain academic integrity rather than expecting students to read academic integrity policies. Fatemi and Saito (2020) have also called for a more standardised approach to teaching academic integrity, including attention to the practical skills associated with citation, paraphrasing, and summarising. The skill of referencing is usually taught at the undergraduate level, so there is often the expectation that postgraduate students have acquired this knowledge in their undergraduate studies and are consequently able to reference correctly. However, a lack of awareness can be attributed to several factors, such as changing disciplinary or cultural conventions. A more nuanced understanding of referencing conventions should, therefore, be explicitly taught, particularly at the start of a doctoral student’s candidature.

Academic integrity software can also be used in a more educative manner to help scaffold students’ understanding. In our Faculty, for example, the text-matching software Turnitin is used to help doctoral students improve their approaches to academic integrity prior to submission of written work to their supervisors, academic publishers, or thesis examiners. This practice version of a Turnitin dropbox emphasises the use of the software as a learning tool, rather than a surveillance strategy, enabling students to discover where they have engaged in poor paraphrasing. While anecdotal, our experience seems to indicate that this approach, in conjunction with educational videos, tutorials, and educator guidance, can scaffold doctoral students’ understanding of academic integrity according to disciplinary conventions. This form of explicit instruction can be provided throughout a student’s doctoral journey, in order to raise an awareness of academic integrity practices as well as lay a solid foundation for the student’s future study and career.

Another consideration is that doctoral students may come from a different cultural academic context where different writing practices are valued. In designing and implementing these interventions, we consequently argue that academic integrity training should not only target the implementation of research integrity codes from above (Sarauw et al. 2019). We believe that the training should also be a site for doctoral students to negotiate, question, and affirm institutional codes in order to develop their individual reflexivity and responsibility as junior academics (Sarauw et al. 2019). By allowing reflection on professional practice, educators and supervisors will provide a space for doctoral students to discover and apply appropriate integrity practices. It is also important to note that, as Hyytinen and Löfström (2017) highlight, academic staff may also require pedagogical training on how to effectively teach research integrity and ethics. Targeting these interventions at both institutional and individual levels could help to create an institution which supports, facilitates, and provides a conducive environment for academic integrity where reflexive and responsible researchers can flourish.

Support for academic literacy development

Building confidence in writing ability by modelling the writing process is an important way to scaffold academic integrity for PhD students. Fatemi and Saito (2020) noted that a lack of self-confidence and lack of knowledge in relation to academic literacy skills were key causes of plagiarism. Cisco (2020b) also reported that literacy interventions that target academic and disciplinary literacy, in addition to reading and writing academic texts, can help doctoral students develop the academic skill set required to thrive in academia. Emerson et al. (2005) highlighted that a lack of academic integrity in students’ writing is often a consequence of a lack of understanding of the academic writing process. Experienced academic writers, however, realise that academic writing is indeed a process (Wilson and Cutri 2019). For instance, manuscripts often undergo multiple revisions and significant editing prior to submission for publication. Peer review then leads to further changes before final publication. Modelling this process for students can be an eye-opening experience, helping students overcome some of the feelings associated with writing anxiety and the imposter phenomenon (see, for example, the experiences of Lam et al. 2019).

Consequently, we advocate for the establishment of learning communities such as writing groups. Doctoral writing groups offer a safe and low-risk environment where students can build their academic writing skills in a peer learning environment (Aitchison and Guerin 2014; Cahusac de Caux et al. 2017). It has been shown that the peer feedback component of these types of writing groups helps students to build their writing confidence, foster greater reflective practice, and encourage them to take ownership of their writing style (Cahusac de Caux et al. 2017; Lam et al. 2019). Encouraging doctoral students to join, or indeed set up their own, learning communities could, therefore, significantly improve students overall learning experience during their candidature. It is important to note, however, that students often tend to seek peer support from fellow students who come from a similar cultural or linguistic background. Accordingly, it is important to consider how the benefits of writing groups with members from a variety of backgrounds and perspectives can be best showcased to students.

Changes in supervisory practices

We believe that the supervision process should enable students to develop their academic integrity. The role of a research supervisor is crucial in doctoral students’ academic endeavours. Supervision entails an enculturation function in which students are encouraged to be a member of the disciplinary community in academia through role-modelling and apprenticeship (Lee and Murray 2015). This can be achieved through exposure to exemplary texts to analyse, encouragement for students to produce their own texts based on these exemplars, and provision of advice and constructive feedback on students’ writing.

In addition, supervision should also enable emancipation where students are encouraged to develop and question themselves and their motivation in writing (Lee and Murray 2015). This aspect is particularly important, as a doctoral student’s identity changes during the writing process (Clarence 2020; Cotterall 2011). Supervisors should, therefore, motivate students to reconceptualise writing not just as a method of completing a thesis, but also as a learning process. As noted by Pretorius (2019 p. 5),

the doctoral journey is more than just a three- to four-year timeframe where a student eventually submits a thesis as evidence of the creation of new knowledge. Rather, the doctoral experience incorporates a variety of opportunities for more in-depth personal development, particularly in terms of intrapersonal wellbeing, academic identity and sense of agency, as well as intercultural competence.

To facilitate this more in-depth personal development, writing tasks from supervisors should be more diverse. This is in line with postmodern scholars’ conception of writing as a method of inquiry (Richardson 2000; Richardson and St. Pierre 2005; St. Pierre 1997). Writing can be a method of self-discovery to explore doctoral students’ deepest desires in undertaking their doctoral projects and consequently their motivation in writing. Pretorius and Cutri (2019) provide a framework for doctoral student reflection based on the “What? So What? Now What” reflective practice model (see also Driscoll 2000; Rolfe et al. 2001) that can help doctoral students explore their experiences during their doctoral candidature. As guiding prompts to write about their writing process, Fernsten and Reda (2011) have also provided 35 questions that can help doctoral students become reflexive writers who can critically identify problems with their writing and texts. This shift to a more reflective approach can reduce writing anxiety because, instead of viewing writing as a high-stakes activity, writing is conceptualised as thinking, analysis, and as “a seductive and tangled method of discovery” (Richardson and St. Pierre 2005 p. 1423).

Conclusion

In this conceptual literature review, we have explored the key factors that are associated with academic integrity in doctoral education. We argue throughout this article that academic misconduct within doctoral studies is underpinned by two significant factors: the imposter phenomenon and cultural differences. Facing these challenges can be overwhelming for doctoral students, which we argue can lead to unintentional academic misconduct. We, therefore, emphasise that approaches ensuring academic integrity do not need to be adversarial or geared towards merely surveillance and punishment. Rather, an educative approach can help to create a culture of academic integrity in the doctoral education setting. We provide practical suggestions to help institutions support doctoral student writing in order to avoid unintentional academic misconduct. In particular, we highlight the importance of explicit academic integrity instruction, support for the development of academic literacy skills, and changes in supervisory practices that encourage student and supervisor reflexivity. We argue that, through the use of these practical strategies, academia can become a space where a culture of academic integrity can flourish.

Availability of data and materials

This literature review is based on analyses of published peer-reviewed research using standard word processing, annotation, and referencing software. No additional data were collected or analysed. No custom software or codes were used to conduct analyses.

Abbreviations

- IPAIR model:

-

Imposter phenomenon and academic integrity relationship model

- TEQSA:

-

Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency

References

-

Aitchison C, Guerin C (2014) Writing groups for doctoral education and beyond: innovations in practice and theory. Routledge, New York

Book

Google Scholar

-

Appadurai A (1990) Disjuncture and difference in the global cultural economy. Theor Cult Soc 7(2–3):295–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/026327690007002017

Article

Google Scholar

-

Australian Qualifications Framework Council (2013) Australian qualifications framework (AQF) second edition. www.aqf.edu.au.

-

Barton D, Hamilton M (2012) Local literacies: Reading and writing in one community. Routledge, London

-

Bourdieu P (1984) Distinction: a social critique of the judgement of taste. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Google Scholar

-

Bretag T (2016) Educational integrity in Australia. In: Bretag T (ed) Handbook of academic integrity. Springer, Singapore, pp 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-098-8_2

Chapter

Google Scholar

-

Bretag T, Harper R, Burton M, Ellis C, Newton P, Rozenberg P, Saddiqui S, van Haeringen K (2019) Contract cheating: a survey of Australian university students. Stud High Educ 44(11):1837–1856. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1462788

Article

Google Scholar

-

Bretag T, Harper R, Rundle K, Newton PM, Ellis E, Saddiqui S, van Haeringen K (2020) Contract cheating in Australian higher education: a comparison of non-university higher education providers and universities. Assess Eval High Educ 45(1):125–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1614146

Article

Google Scholar

-

Bretag T, Mahmud S, Wallace M, Walker R, McGowan U, East J, Green M, Partridge L, James C (2014) ‘Teach us how to do it properly!’: An Australian academic integrity student survey. Stud High Educ 39(7):1150–1169. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.777406

Article

Google Scholar

-

Cahusac de Caux BKCD, Lam CKC, Lau R, Hoang CH, Pretorius L (2017) Reflection for learning in doctoral training: writing groups, academic writing proficiency and reflective practice. Reflect Pract 18(4):463–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2017.1307725

-

Cisco J (2020a) Exploring the connection between impostor phenomenon and postgraduate students feeling academically-unprepared. High Educ Res Dev 39(2):200–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1676198

Article

Google Scholar

-

Cisco J (2020b) Using academic skill set interventions to reduce impostor phenomenon feelings in postgraduate students. J Furth High Educ 44(3):423–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2018.1564023

Article

Google Scholar

-

Clance PR, Imes, SA (1978) The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychother Theor Res Pract 15(3):241-247. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0086006

-

Clarence S (2020) Making visible the affective dimensions of scholarship in postgraduate writing development work. J Prax High Educ 2(1):46–62

Article

Google Scholar

-

Clarke R, Lancaster T (2006) Eliminating the successor to plagiarism? Identifying the usage of contract cheating sites. In: the Proceedings of the 2nd plagiarism: prevention, practice and policy conference, Newcastle, United Kingdom, JISC plagiarism advisory service

Google Scholar

-

Cotterall S (2011) Doctoral students writing: where’s the pedagogy? Teach High Educ 1(4):413–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2011.560381

Article

Google Scholar

-